NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Why Plants are Seeding Climate Studies

The National Museum of Natural History’s herbarium is helping botanists research climate-driven changes in plants, their biology and their abundance

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Butterfly_perched_on_a_sunflower_in_a_field_of_sunflowers.jpg)

For many, the coming months promise to be even hotter than last year. But global warming is interrupting more than fun summer plans. It also affects plants.

“Climate change is affecting plants in many different ways —where they can live, when they flower, and even changes in leaf shape,” said Gary Krupnick, a botanist in the Department of Botany’s plant conservation unit at Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

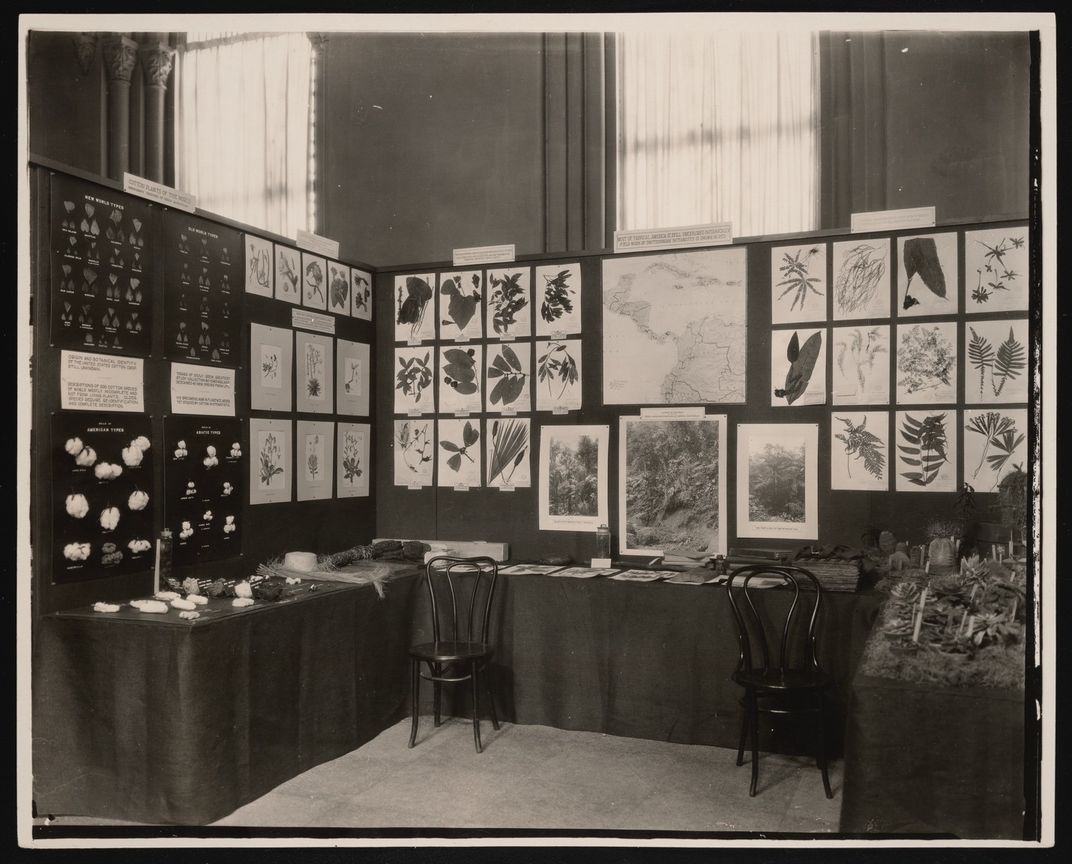

By studying living plants and their leafy predecessors, scientists like Krupnick can see how plants have adapted to environmental fluctuation over the last century. Their research finds its roots in the United States National Herbarium's 5 million plant specimens.

“All of these specimens come with a place where and a time when they were collected. We are using that information to chart how species’ appearances and distributions have changed,” said Krupnick.

Fertile ground for research

Although founded in 1848, the herbarium houses plants collected from centuries ago to today. Most of these specimens have been pressed and placed in systematized folders for botanists to continue to study throughout time.

“These are preserved snapshots of the past. They are proof of the way things were,” said Erika Gardner, a botanist on the herbarium’s collections management team. “Without having that physical information, what we know would all be hearsay.”

When museum scientists began adding to the herbarium roughly 200 years ago, they made careful notes of plants’ physical characteristics and habitat ranges. Today, botanists can peer backwards to see how these notes correspond to increases in greenhouses gases like carbon dioxide.

“We can correlate a lot of those changes with the changes in our atmosphere’s carbon dioxide levels,” said Krupnick.

Pollen’s unbe-leaf-able usefulness

One of the ways Krupnick and his colleague Lew Ziska, a plant physiologist at the University of Columbia, gather information about plants’ responses to climate change is through the plant’s leaves and pollen.

Pollinators, like bees, use pollen as a nutritious source of food filled with protein made from nitrogen. But nitrogen also plays an important role in photosynthesis. Plants use it to break down carbon dioxide, which when combined with sunlight and water, creates sugars and carbohydrates. So, as carbon dioxide increases, the plant must use more nitrogen for photosynthesis. That means less nitrogen is available for plant parts like leaves and pollen.

“Lew’s research found that there’s a lot less nitrogen in the herbarium’s pollen grains today than there were 100 years ago. Bees that feed on pollen grains with lesser amounts of nitrogen, or protein, are getting a lot less nutritious food than their ancestors,” said Krupnick.

Krupnick also analyzes the specimens’ labels to tell whether a plant species has become endangered. Since labels include what locations and date a specimen was gathered, they can show whether a species was common or rare in nature.

“That information goes into an algorithm to determine if the plant is rare enough that we need to do more fieldwork to gather more data,” said Krupnick. “Doing this helps us weed out safe species so that our energy, money, time and person-power can be focused on preserving potentially endangered plants.”

Planting seeds for future generations

The National Museum of Natural History’s herbarium is helping botanists research climate-driven changes in plants, their biology and their abundance. To maintain an updated collection, museum staff are always receiving and storing new arrivals.

One source of new additions is the U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s Seeds of Success program. The program collects seeds from native plants to rehabilitate ecosystems impacted by natural disasters like fires — which are growing more common and more severe from climate change. The herbarium stores voucher specimens of the seeds’ species.

"In order to collect seeds from plant populations, you need a physical pressed plant, or voucher specimen, to show where the seeds you collected came from,” said Gardner.

Voucher specimens are integral to the herbarium. They are resources for climate research, by scientists like Krupnick, in ways that their original collectors could never have imagined. The museum’s botanists hope future generations will surprise them in the same way.

“The valuable thing for me is working with these specimens to preserve them for perpetuity. I love thinking about what people will be able to learn from them in the future,” said Gardner. “Who knows what discoveries lay further down the road.”

Stay tuned for the next story in the Evolving Climate series on May 13. We will show you how scientists in the museum’s Department of Entomology use living and preserved fungus-feeding ants to unravel how Earth’s co-dependent species are responding to climate change.

Evolving Climate: The Smithsonian is so much more than its world-renowned exhibits and artifacts. It is an organization dedicated to understanding how the past informs the present and future. Once a week, we will show you how the National Museum of Natural History’s seven scientific research departments take lessons from past climate change and apply them to the 21st century and beyond.

Related Stories:

What Fossil Plants Reveal About Climate Change

How Biominerals are Stepping Stones for Climate Change Research

Get to Know the Scientist Behind the Smithsonian’s 140,000 Grass-Like Sedges

How to Press Plants from Your Backyard

100 Years Ago, Poppies Became More Than Just Flowers

Are Pressed Plants Windows Into World History?