NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Get to Know the Scientist Behind the Smithsonian’s 140,000 Grass-Like Sedges

Learn more about these grassy plants and what they can tell us about sustainable life on Earth.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/A_green_and_yellow_plant..jpg)

Thousands of years ago, the ancient Egyptians went to the banks of the Nile river to pull a tall grass-like plant from the soggy soil along its banks. This plant, called papyrus, was used to make paper — an upgrade from the clay tablets that had revolutionized communication.

But the plant’s significance reaches beyond the literary world. Papyrus belongs to a family of plants called sedges. They are grass-like plants that grow in wetlands around the globe, playing a crucial role in human and environmental health.

To celebrate World Wetlands Day, we talked with Dr. Mark Strong, a Botanist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, to learn more about these grassy plants and what they can tell us about sustainable life on Earth.

“Papyrus” is common in our shared vernacular but “sedges” are not. What are sedges? And why are they important?

Sedges are the seventh largest plant family in the world. They have about 5,600 species and originated in the tropics. One of the first things you learn about sedges as a botany student is that sedges have edges. That means that their stems are typically triangular whereas grasses have rounded stems.

They’re a major component of wetlands such as marshes, bogs, river shores and pond margins where some species form large colonies. Sedges contribute to nutrient cycling in the ecosystem and create habitats for wildlife.

But wetlands are also important for humans as they maintain and improve water quality, control flooding, sustain fish populations which are important food sources and are aesthetically pleasing.

How did you get into researching sedges?

I actually began my career wanting to be an ornithologist and study birds. I spent a lot of hours learning bird calls in the field and from recordings. I hoped someday to visit Costa Rica and meet Alexander Skutch who was a resident ornithologist there. I had read a lot of his books on the habits of Costa Rican birds.

I wanted to work at the Smithsonian in the Birds Division. So, I went to inquire about whether they needed assistance with any ongoing projects but was turned down at that point. In retrospect, this began my career in wetlands.

Wetlands are a great place to study birds. I was participating in bird surveys in wetlands when I became curious about what species of sedges I was seeing. Their fruits are very distinctive. I soon became hooked on identifying any sedges that I found. By the time I started my graduate studies, I did find work at the Smithsonian. But in the Department of Botany, not the Birds Division.

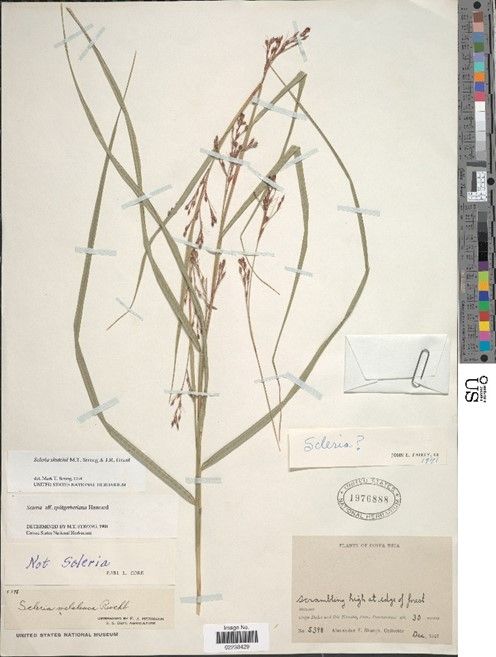

The National Herbarium has more than 5 million specimens including sedges. What is so special about the sedge collection? And how do you use it in your research?

We have 140,000 specimens in the Cyperaceae collection that serve as a resource for botanists around the world to study. Over 3,500 of these specimens are not identified and some of these may represent new species. I have discovered and described about 50 new species from the collection. We also have researchers from South America, in particular, that come to study the collection on a regular basis.

About 58,000 specimens are Carex (the largest genus of the Cyperaceae family). They are represented worldwide and account for 40% of the collection.

I use the collection to produce more definitive species descriptions. It allows me to study a wide range of specimens occurring over a wide geographical area. The data from the specimens can also be used to define habitat, distribution, and what elevation range the species grows in. I also know there are new species waiting to be discovered in the sedge collection.

Do you have a favorite specimen in the collection?

Yes. It’s a species that grows in Costa Rica that I named for Alexander Skutch. Even though he was trained as an ornithologist, when he first went to Costa Rica, he started collecting plants. I was happy to be able to name this for him as Scleria skutchii (Skutch’s nutrush).

Sedges do a lot for their ecosystems and humans. What do they tell us about life on Earth?

Sedges’ striking diversity clearly illustrates the range of evolutionary adaptations plants have developed in response to their changing environment. They tell us that diversity is the key to healthy ecosystems and sustainable life on Earth.

Meet a SI-entist: The Smithsonian is so much more than its world-renowned exhibits and artifacts. It is a hub of scientific exploration for hundreds of researchers from around the world. Once a month, we’ll introduce you to a Smithsonian Institution scientist (or SI-entist) and the fascinating work they do behind the scenes at the National Museum of Natural History.

Related Stories:

Meet One of the Curators Behind the Smithsonian’s 640,000 Birds

Say Hello to the Smithsonian’s Newest Mollusk Expert

Meet the Scientist Using Fossils to Predict Future Extinctions

How to Press Plants from Your Backyard