When the Monuments Men Pushed Back Against the U.S. to Protect Priceless Art

A new show spotlights the scholars who protested the controversial, post-war American tour of 202 German-owned artworks

:focal(682x497:683x498)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/27/6b/276b350b-3353-4f03-b217-47f3c4f34382/screen_shot_2021-07-08_at_34748_pm.png)

It may have been the first blockbuster art exhibition of modern times.

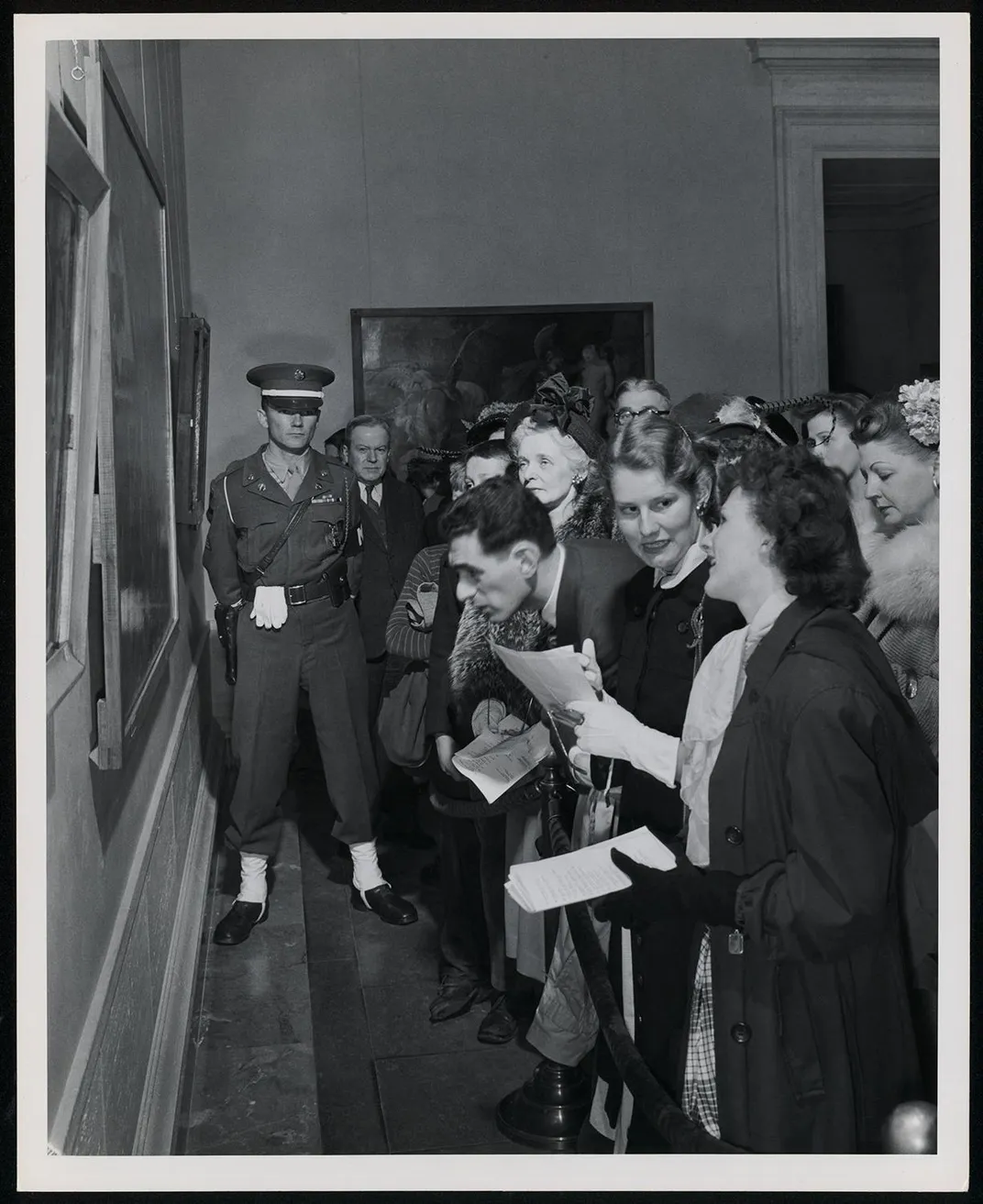

In late 1945, as Europe took its first steps toward rebuilding post-World War II, the United States government shipped 202 paintings by famed artists—including Botticelli, Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Vermeer—from Germany to Washington, D.C. Beginning in 1948, the works were exhibited at the National Gallery of Art before traveling to major museums in 13 other cities, including Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston, Detroit and San Francisco.

All told, a record-breaking 2.5 million Americans saw the exhibition during its cross-country tour. But while audiences were enthusiastic, many onlookers also expressed outrage: Just a few years earlier, Allied forces had rescued these paintings from a salt mine in central Germany where the Nazis had housed thousands of evacuated artistic treasures.

The U.S. returned the artworks to Germany in 1949. But officials’ decision to transport and tour the German-owned paintings (they had previously resided in the collections of the State Museums of Berlin) around the country was “morally dubious,” curator Peter Jonathan Bell tells the Art Newspaper’s Martin Bailey. Now, in a new exhibition at the Cincinnati Art Museum (CAM), co-curators Bell and Kristi A. Nelson unpack the complicated intersections between art and politics in the post-war era by tracing the history of the so-called “Berlin 202.”

“Paintings, Politics and the Monuments Men: The Berlin Masterpieces in America” opens today and runs through October 3. Per a statement, the show will not travel anywhere else. Four of the original “202” are featured, including Sandro Botticelli’s Ideal Portrait of a Lady (1475–80), on loan from Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie, and Fra Filippo Lippi’s Madonna and Child (1440), on loan from the National Gallery in D.C., as Susan Stamberg reports for NPR.

The exhibition’s timeline begins in early 1945, when Allied and Soviet forces advanced into Germany during the final months of World War II. As they moved forward, troops came face to face with the full scale of Nazi atrocities, foremost among them concentration camps and mass graves of genocide victims.

Allied forces also recovered some of the staggering amounts of cultural heritage that the Nazis had systematically looted and hidden in secret locations around the country. These works included famous gems like the Ghent Altarpiece, the paintings of so-called “degenerate” modern artists and art created by Jewish people murdered during the Holocaust.

Crucial to cultural restoration efforts were the “Monuments Men,” a group of roughly 350 men and women who comprised a special Allied unit dedicated to preserving European heritage under threat during the war. Formally known as the Monuments, Fine Art, and Archives program, the unit consisted of art scholars, curators and academics, writes Tana Weingartner for WVXU. The team relocated millions of artworks to safe locations and protected iconic paintings such as Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper from bombing raids.

“Without the [Monuments Men], a lot of the most important treasures of European culture would be lost,” art historian Lynn H. Nicholas told Smithsonian magazine’s Jim Morrison in 2014. “They did an extraordinary amount of work protecting and securing these things.” (The group’s efforts later inspired a 2014 movie starring George Clooney.)

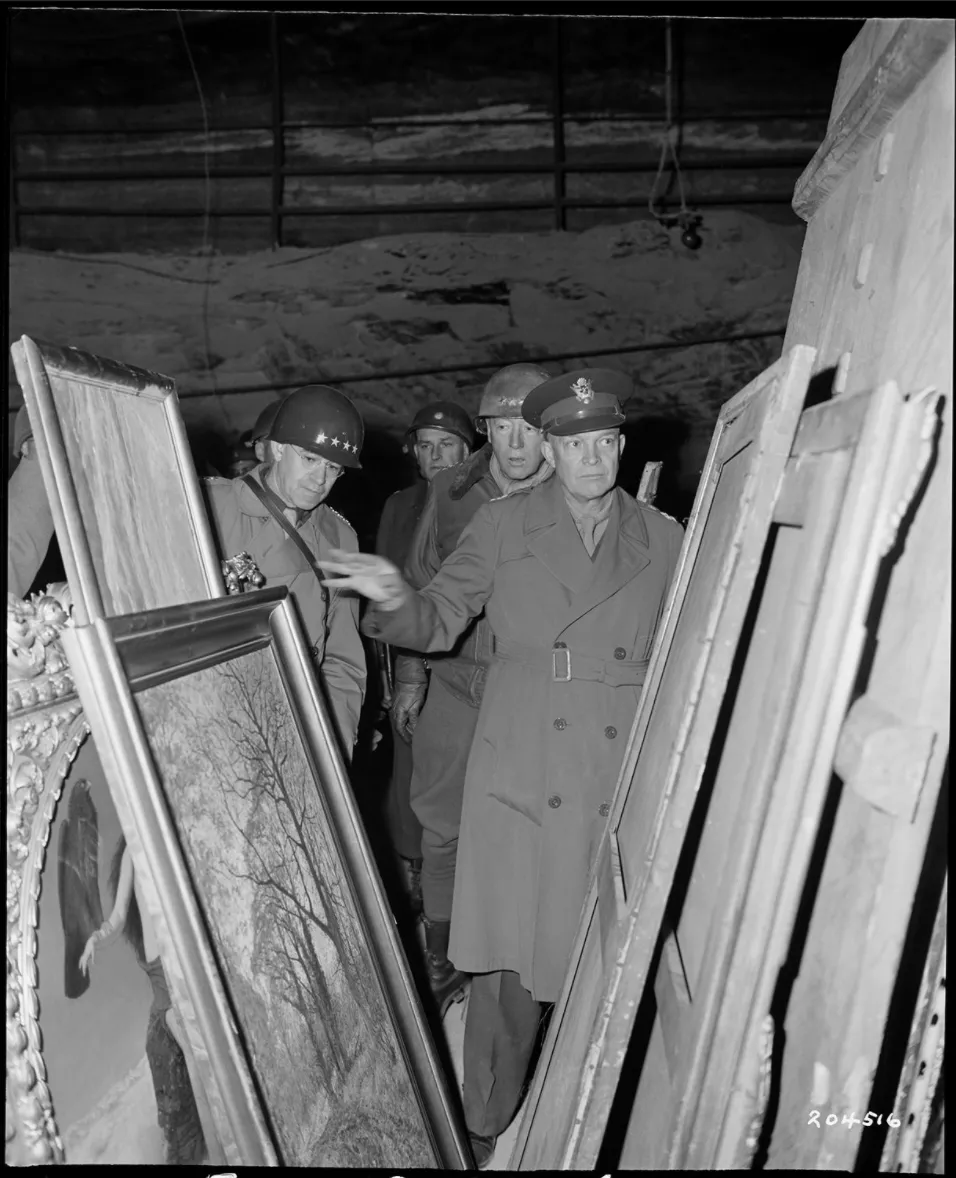

The U.S. Army discovered one trove of hidden artwork in a Merkers salt mine, where crates of paintings were stashed alongside rows of gold. Future president Dwight D. Eisenhower, then a top general, went into the mines himself to inspect the loot; later, the Monuments Men packaged and moved the artworks to a storage depot in Wiesbaden.

Most of the paintings discovered in the salt mine were soon returned to their former owners. But Eisenhower decided to temporarily ship 202 of the works to America—ostensibly for “safekeeping,” according to the Art Newspaper. Comprised mostly of Old Master art from the 16th through 18th centuries, these paintings went on to tour a host of major American museums.

Eisenhower’s decision faced pushback from a group of Monuments Men led by Wiesbaden storage unit director Walter I. Farmer. An Ohio native, Farmer risked being court-martialed when he led 32 of his colleagues in writing a letter protesting the move, noting that the unnecessary transport could seriously damage the valuable art, as Cliff Radel reported for the Cincinnati Enquirer in 2014. Farmer would later describe the choice as “plunder,” per the Art Newspaper.

In their letter, the signees argued that the 202 Berlin artworks should be immediately returned to the rightful possession of the Prussian state and German people. Known today as the Wiesbaden Manifesto, the missive “may have been the only collective act of protest by U.S. officers in World War II,” according to the statement.

Museum leaders in the U.S. likewise protested the display of the works. Congress eventually passed a bill sending the works on tour in 1948, as Karen Chernick reported for Smithsonian in 2019.

The U.S. Army faced “competing desires to do the right thing in terms of international diplomacy and cultural patronage,” Bell told Smithsonian in 2019. “[T]here’s the desire to preserve the paintings, and then there’s also the public demand. This is a collection that most Americans would never be able to see, and that’s when Congress got involved and legislated that they needed to go on this tour.”

In the statement, Bell adds, “This exhibition offers a valuable look into a landmark event in the history of art and twentieth-century geopolitics. The fate of the ‘Berlin 202’ and the broader context of how art was used in the World War II era has affected how we think about ownership and value and cultural patrimony, and how we look at art today.”

“Paintings, Politics and the Monuments Men: The Berlin Masterpieces in America” is on view at the Cincinnati Art Museum in Ohio through October 3.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)