He was a world traveler who rarely left home, yet he plotted a course through history for Britain. George III, who reigned from 1760 to 1820, was a pathbreaking monarch and an armchair general whose thirst for knowledge led him to collect more than 55,000 maps, charts, prints and manuals to savor in his private library. To mark the bicentennial of his death, the Royal Collection Trust has digitized George’s colorful cache of military maps and documents, some of which date back to as early as the 1500s. Some represent rough sketches. Other items include highly polished engravings, vivid orders of battle and finely drawn landscapes that depict bygone theatres of peace and war.

The maps also reveal a tantalizing new portrait of the king, reflecting what he knew of the world beyond Windsor Castle, and the making of a very modern military mind. While the American Revolution marked a turning point for empire and colonies alike, it’s worth knowing that much of George’s life was marked by war. As Britain battled through decades of fighting with European and Asian powers, George heeded the history of each win or loss. His universes of interests—astronomy and art, science and culture—all collided in the private library that he built, book by book, behind the walls of Windsor. George’s love of precision, evident in the way he dated letters down to the minute, made him ideally suited to study military history.

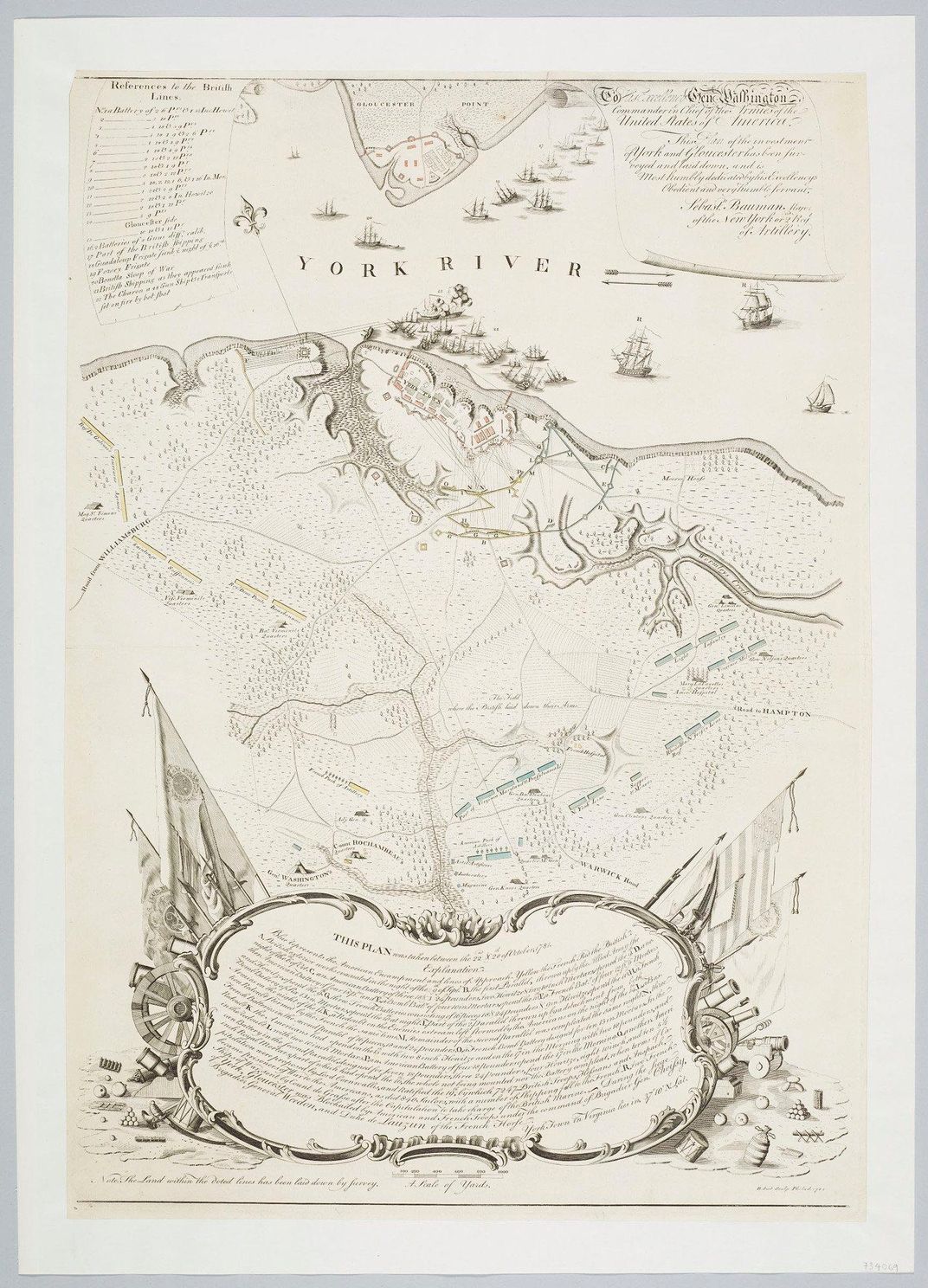

The king was, as historian Rick Atkinson observed, “a demon for details.” Poring over his maps, George counted blankets for the British soldiers facing far-off troops. He tallied cannon in the French fleet and sized up foreign uniforms. He eyed the hasty fortifications of American militia. Anxiously, he peered back at the past for Dutch naval lessons. And as he walked the halls of present-day Buckingham Palace, George glanced over the custom-built mahogany stands that held maps like this Philadelphia print of Yorktown in 1781, “The Field where the British laid down their Arms.”

Here are a few of the maps that sparked George’s imagination. You can learn more about how history remembers America’s last king–in manuscripts, memories, medals, and coins–here.

1628, Siege of Havana

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/8e/0c8e28fa-876b-4e59-99c6-0ab57381bcb7/951122-1578415861.jpg)

The king was a keen apprentice of military science from a young age. Carefully reconstructed scenes like this one by the Dutch engraver David van den Bremden, which shows the clash in the Caribbean between Spanish and Dutch fleets in the summer of 1628, gave George new ways to think about naval strategy. For an island nation, establishing maritime power was vital. Between 1660 and 1815, the British Navy vied for dominance at sea, faltering before the Dutch Navy’s prowess before finding success in a pivotal set of contests against the French. George nurtured the British Navy’s growth at home, mindful that distant battles could reshape the fate of empires.

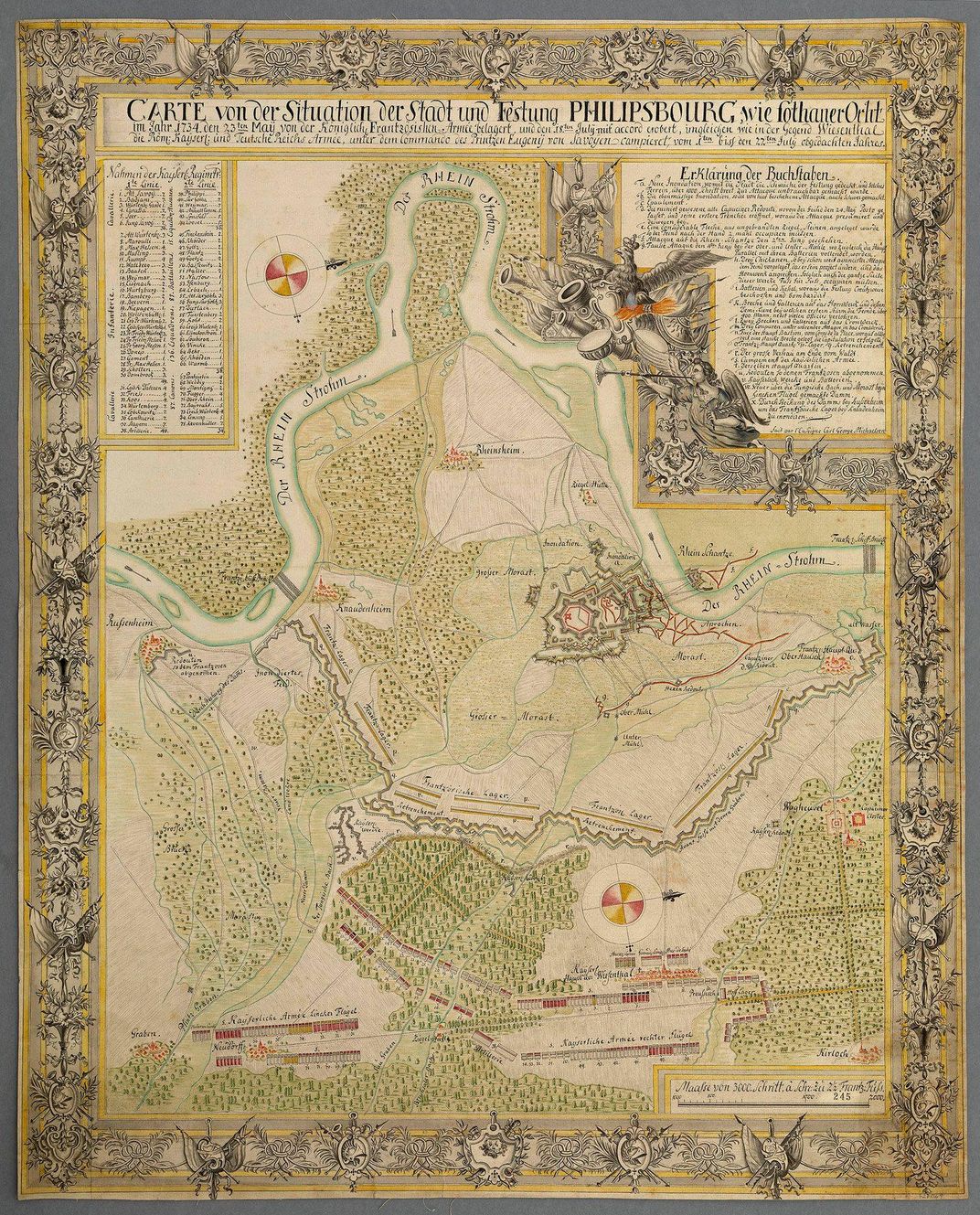

1734, War of the Polish Succession

French victories and defeats, in particular, drew George’s eye as he deepened his appreciation for military arts. Created in pencil and watercolor, then spread across seven separate pieces of paper, this ca. 1734 map recreates the French siege on Philippsburg from May 23 to July 18, 1734. Zoom in for the delicate detail of the topography and the French camps. This map tells of a draining win for the French. Some 60,000 men marched on the Austrian-held fortress, fruitlessly, until a relief column of 35,000 more joined what became a month-long siege, and the fort surrendered. To George’s mind, the onslaught revealed how French generals chose to split their forces and changed their siege tactics over time. Other Philippsburg maps in his trove zigged and zagged with lines of mortar and cannon fire, tracing the siege’s action from day to day.

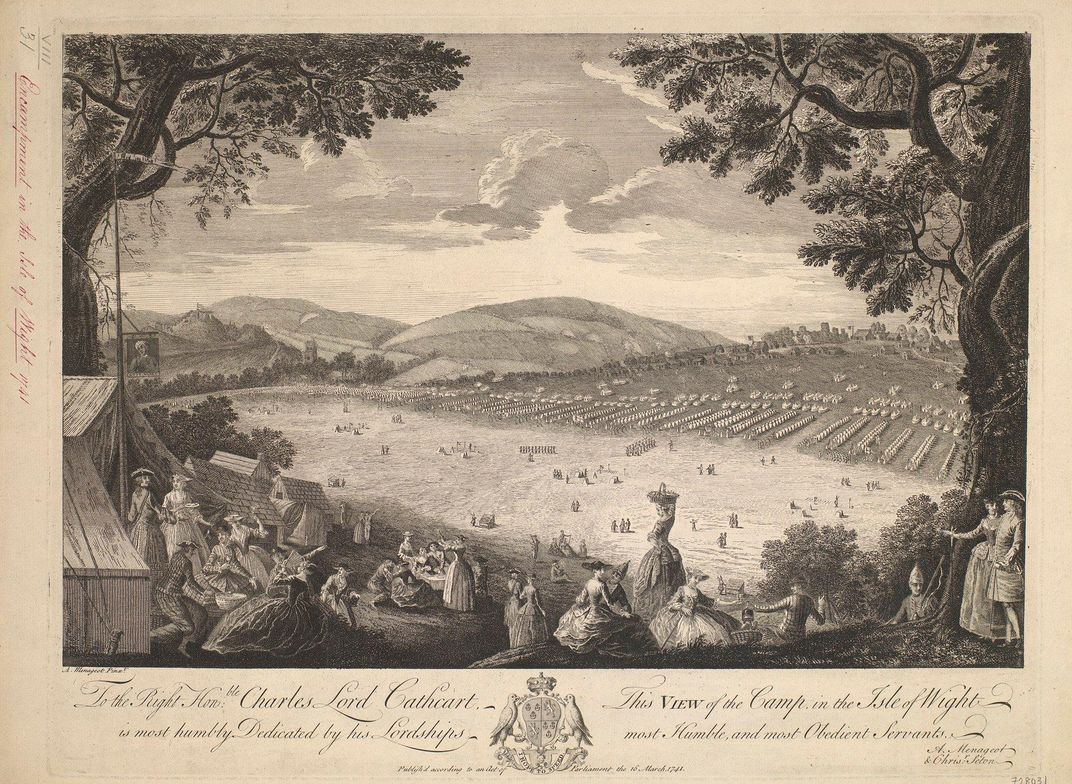

1740, Encampment at Newport, Isle of Wight

Not all of George III’s military maps trove was centered on war. Brief moments of peace and calm bubble up, too. Published in tandem with a plan for the encampment, this etching features elegantly dressed women and men lingering over their picnics. Leisurely, they soak in a scenic view of the soldiers’ tents laid out neatly below. As scholars think about the social history of the military, and how the enlisted men interacted with society, it’s fascinating to consider George’s perspective and encounters with his troops. The king loved touring his fleet at Portsmouth and dining aboard ship with officers. George envisioned army and navy alike as cultural institutions that protected British prosperity and symbolized world power.

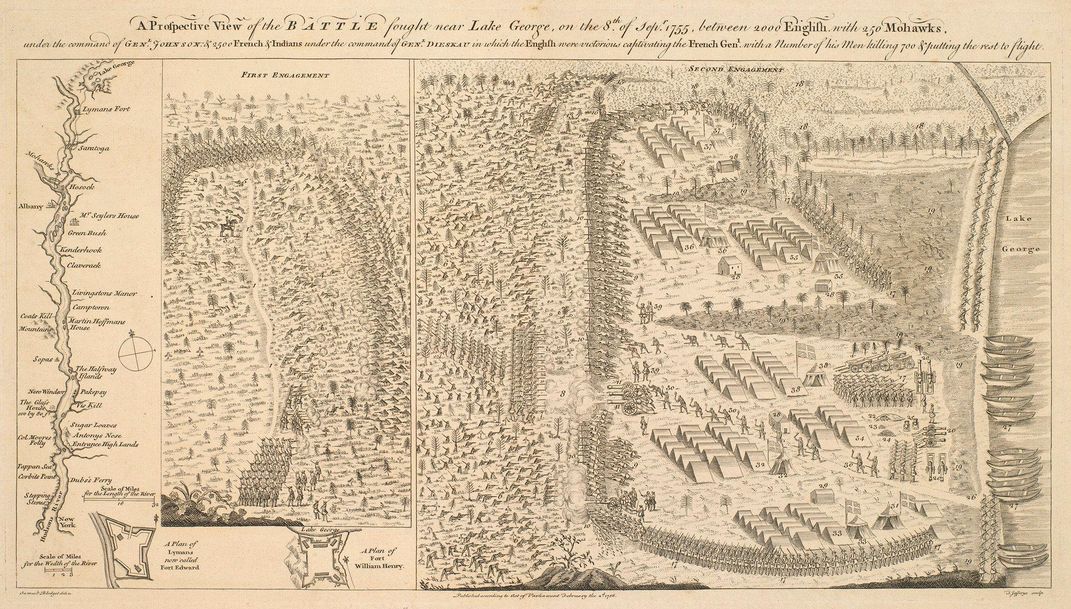

1755, Seven Years’ War

At the age of 22, George inherited the throne and a kingdom at war. As he fretted from the south of England, this conflict ripped Europe in two and wrenched North America through multiple waves of imperial violence. At Lake George, New York, British, French, Native, and Canadian forces clashed repeatedly, culminating in a British victory and marking a major turning point in the war. Noted cartographer Thomas Jefferys, appointed as George III’s geographer in 1760, produced this map, entitled “A Prospective View of the BATTLE fought near Lake George, on the 8.th of Sep.r 1755, between 2000 English with 250 Mohawks, / under the command of GEN.L JOHNSON: & 2500 French & Indians under the command of GEN.L DIESKAU.” For George, the Seven Years’ War (known as the French and Indian War in the U.S.) also meant a political prizefight at home. Wary of a Spanish alliance with France, he tangled with minister William Pitt the Elder, who sought to stretch British naval resources and widen the war’s scope—a move that led to Pitt’s ouster. George never set foot in New York, but this map likely staked out a personal and political achievement in his memory.

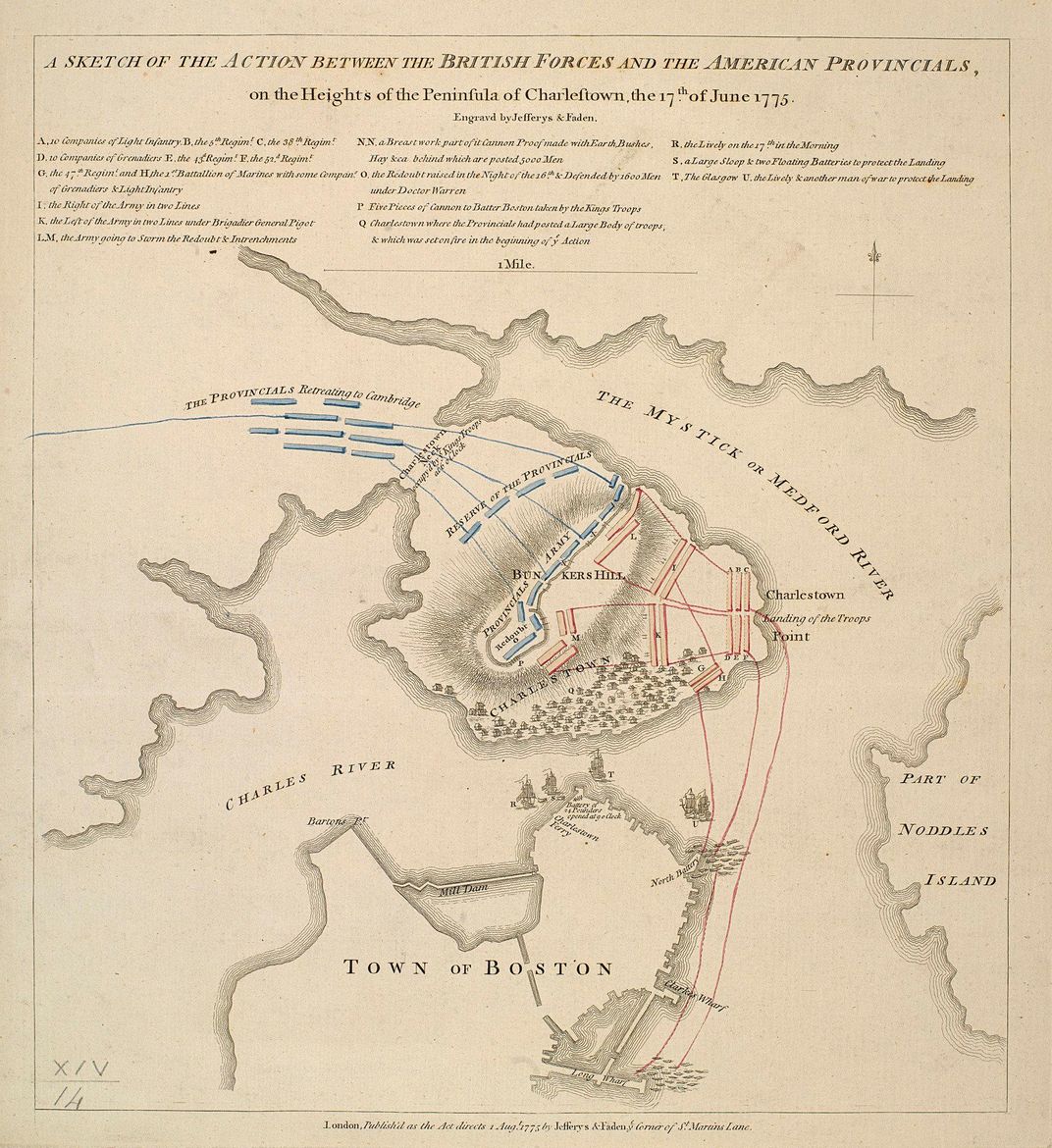

1775, Battle of Bunker Hill

How did George III get his news about the American Revolution? Maps like this one, despite their flaws, unlock some of the story. Five days after news of the Battle of Bunker Hill’s outcome reached London, mapmakers like Jefferys scurried to set it down on paper. George’s cache includes Jefferys’ effort, the earliest published plan of the battle. The mapmaker’s topography was a little off, and his drawing was less than polished, but Jefferys conveyed a significant win for the British. That victory would sour in the coming weeks. A supply shortage strained British control of Boston, and George Washington arrived in Cambridge to command the Continental Army.

1781, Battle of Yorktown

One of the most poignant entries in George III’s maps trove is this hand-colored 1781 map of Yorktown, where a combined force of 9,000 British and German troops, were defeated by an American and French army numbering 19,000 strong. Want to see where and how the Revolutionary War ended? You can find the American forces marked in blue, the French in yellow, and the British in red. A dozen copies of this rare map exist in the United States. Search for the spot on the map marked, “The Field where the British laid down their Arms.”

:focal(282x205:283x206)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7e/60/7e604afd-d9d2-4ab5-81de-023bc7266584/maps-mobile.jpg)

:focal(611x365:612x366)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/d2/f2d2127e-39bb-4f12-933b-c3f8521a62c9/maps-social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SEG_Headshot.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SEG_Headshot.jpeg)