How the Nazi Regime Upended the Lives of These Bavarian Villagers

A new book draws on long-overlooked sources to chronicle how Oberstdorf’s residents navigated the rise—and dictatorship—of Adolf Hitler

:focal(640x451:641x452)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8f/91/8f912ab2-9ecb-49e8-bfa4-d17b4dc69df8/16_leni_and_julius_lowin_with_ernest_junger_in_oberstdorf.jpg)

On the evening of March 5, 1933, the inhabitants of Oberstdorf, a Bavarian village some 100 miles southwest of Munich, began making their way to the marketplace, eager to hear what their mayor had to say about the federal election held earlier that day. The National Socialist German Workers’ Party (also known as the Nazi Party) had wrested control of the government; little did the villagers know it would be the last truly democratic election Germany would see for 13 years.

Among the crowd, there was a palpable sense of anticipation as everyone, warmly wrapped against the cold night air, waited for events to unfold. Many of those present no doubt chatted to their friends about the sight they had witnessed the night before, when, as a prelude to the election, numerous bonfires had been lit in the mountains: Nazi supporters had ignited a huge swastika formed of flickering flares high up on the Himmelschrofen mountain.

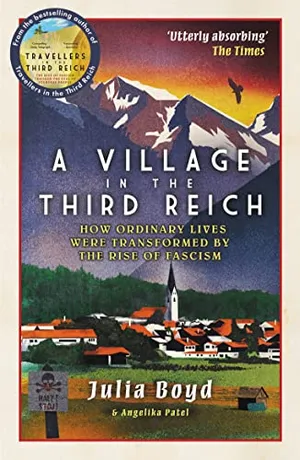

A Village in the Third Reich: How Ordinary Lives Were Transformed by the Rise of Fascism

An intimate portrait of German life during World War II, shining a light on ordinary people living in a picturesque Bavarian village under Nazi rule

It was not quite five weeks since January 30, when Adolf Hitler had been sworn in as Germany’s new chancellor, but it was clear to everybody—even in this far-off Alpine village—that the political landscape had changed.

Shortly after 8 p.m., the faint sound of beating drums grew louder as a unit of paramilitary storm troopers marched into the marketplace, carrying torches and shouting out party slogans. The villagers had long since become accustomed to the presence of these noisy brownshirts on their streets, even if they did not necessarily approve. But if the trappings of the Nazi Party were not to everyone’s taste, Hitler’s message and style of leadership had caught the imagination of enough of the electorate to result in Oberstdorf casting more votes for the Nazis than for any other party.

Dominated by the church of St. John the Baptist, its spire visible for miles around, the marketplace was also where the largely Catholic Oberstdorfers came to remember their fallen soldiers at memorials to the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and 1871 and to World War I, the latter housed in a small chapel next to the church. In the middle of the square stood two flagpoles, one flying the black, white and red flag of the old German Empire and the other a Nazi swastika.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/59/63/596320e4-4d29-497f-94f0-739c78a43d21/oberstdorf_2.jpg)

The crowd fell silent as a gun salute marked the official start of the rally. Then, an “outsider”—a relative newcomer to Oberstdorf—stepped onto the podium, causing surprise among the villagers who had been expecting their mayor to speak. For those not already in the know, it was soon apparent that this man was the village’s new National Socialist leader.

Later, as the crowd dispersed and returned to the warmth and security of home, even those villagers who had voted for Hitler wondered exactly what the future held in store.

Why study the lives of the Oberstdorf villagers? It’s through their records that historians understand how the genocidal dictatorship of Hitler’s Nazi Germany happened, how fascism gains power and how attacks on the most vulnerable populations eventually affect the most comfortable. In learning about these experiences, those facing authoritarianism today, in all its contours, may recognize that in a fascist regime, the benefits of being at the top are short-lived, and eventually, everyone suffers.

By closely following these people as they coped with the day-to-day challenges of life under the Nazis, there emerges a real sense of how ordinary Germans supported, adapted to and outlasted a regime that, after promising them so much, in the end delivered only anguish and devastation. Their status as not a part of any group targeted by the Nazi regime ensured their survival, but their stories nonetheless tell magnitudes. Also revelatory are the chronicles of those without privileged status, who perished over the course of the 12 years the Nazis were in power.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e6/25/e6252fc9-279e-4b16-87b2-83a93f372f20/160_reichsparteitag_1109_copy.jpg)

The village lies in a part of Bavaria in a region known as the Allgäu, long recognized for the beauty of its mountains and the toughness of its people. Oberstdorf is uniquely defined by its geographical position as the most southern village in Germany. Once there, the traveler has quite literally reached the end of the road, as only footpaths lead south across the mountains to Austria.

Oberstdorf possesses a particularly well-maintained archive. It contains a wealth of detail on almost every feature of village life under the Nazis—data that in the postwar longing to forget everything to do with the Third Reich and the war and Holocaust it wrought might so easily have been “lost” or abandoned. Other important sources include local newspapers, unpublished memoirs and interviews given by the villagers themselves. Diaries and letters from private collections and documents preserved in various national, state and church archives enrich our understanding as well. Drawing on all these sources, it has been possible to create a remarkably intimate portrait of Oberstdorf during the period between 1918—the end of World War I—and the granting of full sovereign rights to West Germany in 1955.

In the village archive, we encountered foresters, priests, farmers and nuns; innkeepers, Nazi officials, veterans and party members; village councilors, mountaineers, socialists, forced laborers, schoolchildren, Jews, entrepreneurs, tourists and aristocrats. We met Theodor Weissenberger, a blind teenager condemned to die in a gas chamber at age 19 because he was living a “life unworthy of life.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/16/b7/16b7280b-f9c2-4ada-8a0f-f378dd06ec84/15_662_neu_theodorle.jpeg)

Then, of course, there are the soldiers, many of them eager to fight for a dictatorship they had been persuaded to support or simply chose never to question, others opposed to the war from the start. All of life is here: brutality and love; courage and weakness; action, apathy and grief; hope, pain, joy and despair—in other words, the shades of gray that make up real life as we know it, rather than a narrative of heroes and villains.

And as we got to know the villagers better, it came as no surprise to learn that their response to these cataclysmic events was driven as much by practical everyday concerns, the instinct to safeguard their families—from threats both real and imagined—and personal loyalties and enmities as by the great political and social issues of the time.

At the end of World War I, Germans were recovering from defeat. Despite the madness of hyperinflation caused by the punitive measures put forth by the Treaty of Versailles, Oberstdorf had, by the late 1920s, been transformed into a flourishing vacation resort. Even with a constant influx of Germans from the north, bringing with them new ideas and a fresh outlook on the world, the village’s rural roots and religious values remained at the heart of its identity.

Focused on economic recovery, Oberstdorf residents initially ignored Hitler and his new party in Munich. When in 1927, a postman tried to establish a branch of the Nazi Party in the village’s staunchly Catholic community, it was, as he later complained to propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, an uphill struggle.

Like so many of their fellow citizens, Oberstdorfers—deeply Catholic and conservative by nature—were drawn to Hitler by his promise to implement strong government, expunge the ignominy of the Treaty of Versailles, defeat communism and elevate Germany back to its prewar status. By 1930, it became clear that the people of Oberstdorf had changed their minds about National Socialism when Hitler won a plurality of votes in the September federal election.

But when the reality of Nazi rule hit the village two and a half years later, it came as a shock. The city archive holds many records that show how the fascist regime affected even those who were not Jewish, Roma, disabled or any other outsider group. National Socialism, they now discovered, was not just a system of government. It aimed to control every aspect of their lives and reshape centuries-old Catholic traditions in the Nazi image. While many villagers remained loyal to Hitler, they did not take kindly to their first Nazi mayor, who stripped them of all autonomy over their own affairs.

Those who actively supported National Socialism were forced to make adjustments. Anyone who stepped out of line or criticized the regime risked “protective custody” in the newly established camp for political prisoners at Dachau. As the months went by, some villagers found Nazi methods increasingly disturbing, but others, dismissing the more unpleasant rumors as foreign propaganda, remained committed to the regime.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3d/3d/3d3d771c-71ec-436d-a85d-a46c356b7dbd/nl-ahglda_0782_11-01071_copy.jpg)

After the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, sparking World War II, the villagers’ anxiety largely faded, as Germany’s military successes appeared to underpin Hitler’s promise of a quick and total victory. But documents show how their morale plummeted in the months following the failed invasion of the Soviet Union, when, apart from depressing reversals on the battlefield, the villagers also feared receiving news that a loved one was missing or had been killed or wounded. Through the unpublished diaries of a lieutenant and a sergeant who served alongside Oberstdorf’s soldiers in the 99th Regiment of the First Mountain Division, we followed the young men as they fought in Poland, France, the Soviet Union and the Balkans, right up to the final months of retreat and defeat.

Oberstdorf, despite its remoteness, was by no means isolated from the war. Not only did the villagers receive firsthand news of conditions—and atrocities—on the various battlefronts from their soldiers returning home on leave, but Dachau sub-camps and forced labor camps were also located close by. Before the Nazis ramped up their persecution of Europe’s Jews in the early 1940s, Dachau mainly housed prisoners who had told anti-regime jokes, made “defeatist” war comments or illegally slaughtered farm animals.

Dachau’s sub-camps supplied much of the workforce for the various BMW and Messerschmitt factories that sprang up in and around the village in the later stages of the war. A Waffen-SS training camp operated six miles south of the village, while a Nazi stronghold visited regularly by such leading figures as Heinrich Himmler lay only ten miles to the north. On top of all that, evacuees from bombed cities and, later, refugees fleeing the Russians more than doubled the village’s prewar population.

Numerous aspects of Oberstdorf’s Third Reich history make it an absorbing study, but one is particularly surprising. After the first Nazi mayor had been dispatched, his successor, Ludwig Fink, who was known for his robust pro-Nazi speeches, saved the lives of a number of prominent Jews living in the village. He also supported other inhabitants who found themselves on the wrong side of the Nazi legal system. Fink protected, for instance, the parents of a renowned playwright and probably tipped off a Jewish female villager when she was about to be summoned to the concentration camp Theresienstadt.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ad/79/ad79b05c-9480-4bba-a0a3-0e53d536974e/12_familienfoto_fink_rev.jpg)

A surviving list of Nazi Party members includes the names of Oberstdorf men who were also well known for their opposition or indifference to the regime. In the end, they joined the party for any number of reasons—the need to protect their jobs and families but also, sometimes, to make their lives a little easier. This is not to imply that Oberstdorf lacked dedicated Nazis, many of whom remained passionately loyal to Hitler to the end. But a system that forced everyone to conform or risk imprisonment, torture or death makes it challenge for historians to accurately assess why so many Germans—including Oberstdorfers—appear to have been complicit in the Reich’s crimes against humanity.

By putting one village under the microscope, our new book, A Village in the Third Reich, aims to contribute in some small way to our understanding of Germans’ reactions to Nazi rule. As an Oberstdorf native, co-author Angelika Patel had one motive when beginning to research the town in 2005 with the aim of answering a question: How was this possible? How was it possible that the people of her country—parents and grandparents—dragged the world and itself into a murderous abyss of war and genocide?

Why did Germans respond to Hitler in the manner that they did; how did their attitudes to the regime evolve; and, when all hope of a reinvigorated, powerful state under the Nazis had fallen apart and their country lay in ruins, of how did they work their way through to a new beginning? If Oberstdorf’s story has much to tell us, it also leaves many questions unanswered—questions that will forever remain part of the legacy of the Third Reich.

Excerpted from A Village in the Third Reich: How Ordinary Lives Were Transformed by the Rise of Fascism by Julia Boyd and Angelika Patel. Published by Pegasus Books. Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/julia_boyd.png)