A Special Delivery for the Doolittle Raiders

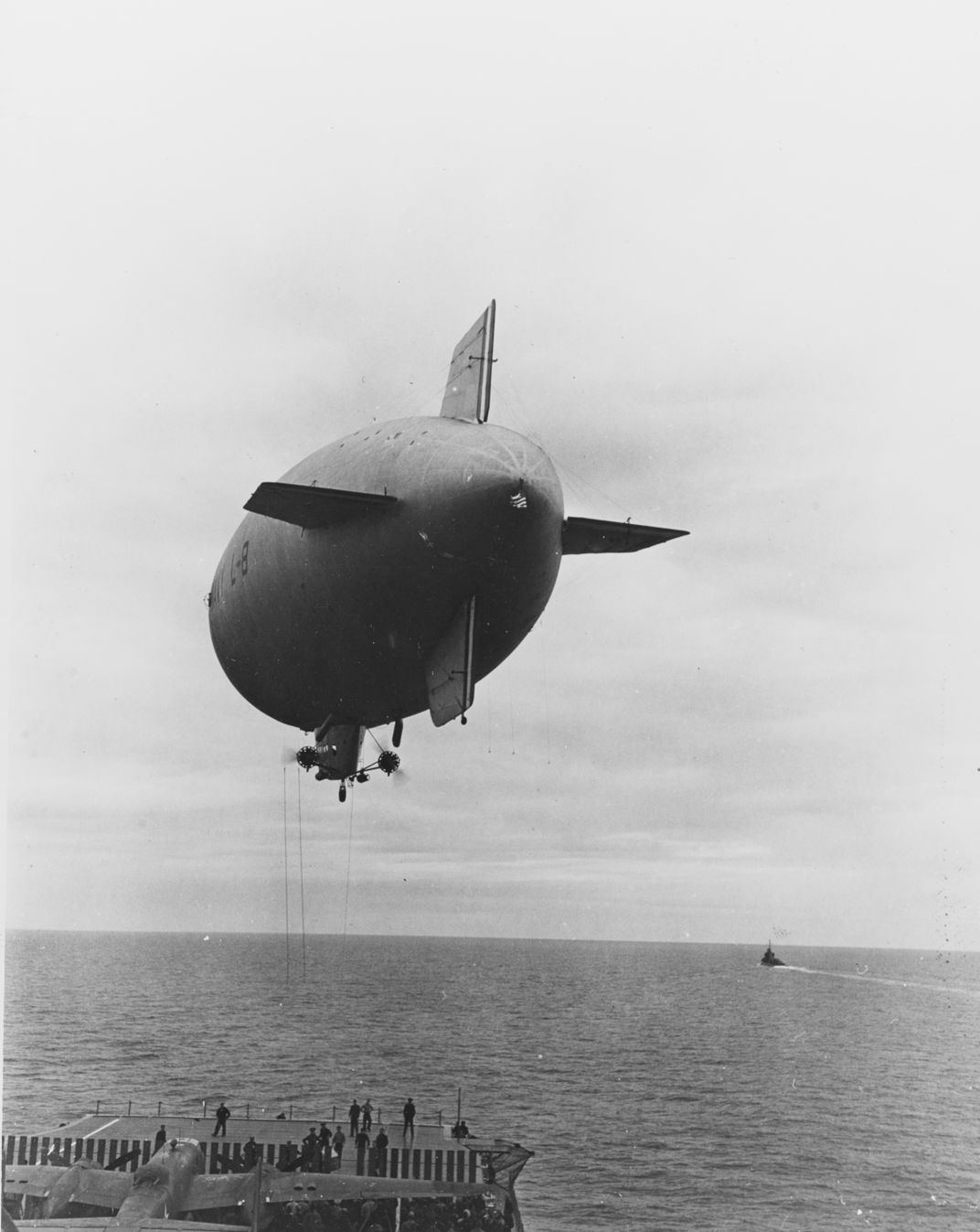

On April 2, 1942, the aircraft carrier USS Hornet was part of a secret plan to strike back at Japan. With no room for aditional airplanes to land on the flight deck filled with B-25 Mitchell bombers, the US Navy turned to the Navy blimp L-8 for a specialy delivery.

:focal(500x375:501x376)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/USAF-92991AC.jpg)

On April 2, 1942, the aircraft carrier USS Hornet left the port in San Francisco Bay carrying a unique cargo of 16 US Army Air Forces B-25 Mitchell bombers. The task force was part of a secret plan to strike back at Japan and accomplish one goal: vengeance for the attack on Pearl Harbor which killed 2,390 Americans, crippled numerous ships of the US fleet, and destroyed several others including the USS Arizona. The mission would come to be known as the Doolittle Raid. Before the fleet could get too far from the shores of the United States, the USS Hornet received a special delivery critical to the mission. With the room on the flight deck taken up by large bombers, the delivery came via a unique vehicle: Navy blimp L-8.

American military and political leaders realized shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor that the US military would need to strike back as quickly as possible against Japan in order to boost morale on the home front. In January 1942, military planners developed the “Joint Army-Navy Bombing Project,” in which Army Air Forces medium bombers would launch from a Navy aircraft carrier after they crossed the Pacific Ocean to be within range of Japan. It was determined that the B-25 medium bomber would offer the best chance of success, with the ability to take off within the length of the carrier flight deck and the range to reach Japan and beyond if launched 500 miles east of Tokyo.

Once the mission was set, aircraft and crews needed to prepare for the special attack, all while keeping the strictest secrecy. Lt. Col. James Doolittle was chosen to lead the attack and command the Army Air Force elements of the mission. B-25 aircraft from the 17th Bombardment Group were modified for the mission, including the addition of extra fuel tanks as well as the removal of several machine guns and any unnecessary equipment in order to lighten the aircraft. Volunteer crews began extensive training under Navy instruction at Eglin Field, Florida, to prepare for the many challenges the mission posed, such as preparing to take the bombers off from the deck of an aircraft carrier, flying at night, and low-altitude flying and bombing. After reaching the West Coast, the USS Hornet was loaded with the 16 modified B-25 aircraft, and the crews and their aircraft set sail toward Japan.

The success of the mission greatly depended on the US Navy and US Army Air Forces working together, as well as the rigorous training and bravery of all involved. One other factor, however, greatly assisted with the success of the mission. Modifications to the B-25 bombers needed for the flight were not complete when they were loaded onto the USS Hornet. The bombers took up the entire flight deck, meaning parts could not be flown to the carrier by plane. The Navy turned to the lighter-than-air fleet in order to deliver 300 pounds of fragile navigator’s domes needed to finish the modifications while en route to Japan. When the war first broke out, the US Navy purchased several small advertising blimps from Goodyear, including the Goodyear Ranger (NC-10A). The Ranger was redesignated L-8, and it would perform the critical supply drop to the USS Hornet only a few days after the aircraft carrier set sail. The L-8 is currently on display at the National Naval Aviation Museum, and is similar in design to the National Air and Space Museum’s C-49 control car which served as L-5 during World War II.

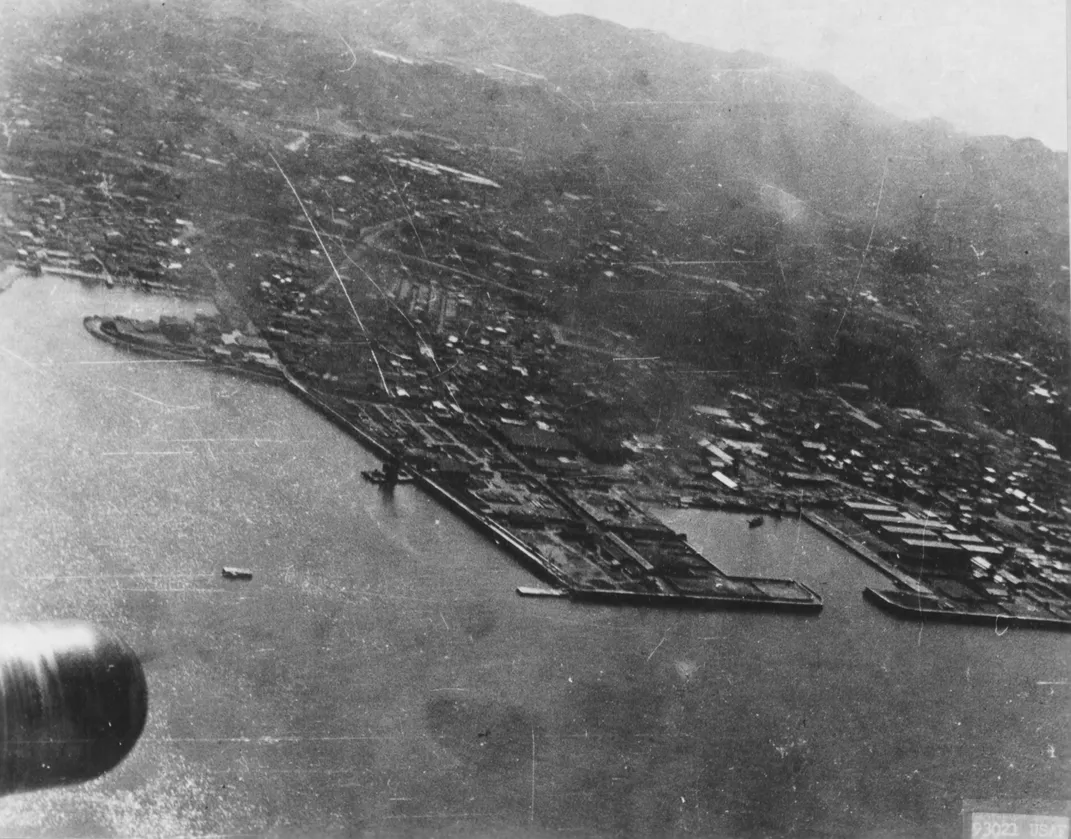

After the critical supply drop was complete, the USS Hornet continued sailing until it rendezvoused with the USS Enterprise, under the command of Vice Adm. William F. Halsey Jr., and several oilers, destroyers, and cruisers to form Task Force 18. Aircraft from the USS Enterprise provided aerial cover for the USS Hornet since the latter’s flight deck was fully loaded with the B-25 bombers. The task force sailed east until April 18, 1942, when they spotted Japanese ship No. 23 Nitto Maru. The US forces sunk the Japanese ship after a short engagement, but not before it sent contact reports back to Japan. The original plan called for the bombers to launch when the task force reached 500 miles from the target, but the alert forced the crews and ships to launch while still 650 miles from Japan. Lt. Col. James Doolittle flew the first B-25 off the deck of the Hornet, and the other 15 aircraft followed within an hour, launching off the deck and getting into flight position.

The flight of the 16 aircraft quickly set course towards Japan, where they would drop high-explosive and incendiary munitions on targets in Nagoya, Kobe, Tokyo, Yokohama, and Yokosuka. The attacks caught the Japanese by surprise and faced little opposition. Although they did not cause great damage like later attacks, the psychological impact alone was devastating to Japanese morale, while boosting American morale in the process. Fifteen of the 16 aircraft flew to China where the crews were forced to ditch their aircraft or crash land them. Three American airmen were killed during these landings, and eight were captured by Japanese forces. Of the eight captured, three were executed and one died while in captivity. Chinese civilians risked their lives to protect the American airmen, including Doolittle, and move them away from the Japanese into friendly areas. The Japanese military attacked Chinese civilians as reprisals for helping the crew, and an estimated 250,000 were killed. The crew of the final aircraft were interned in Russia after successfully flying to Vladivostok.

The US Navy lighter-than-air fleet served from the very start of the war and were vital to the war effort on the Pacific coast, in the Atlantic, as well as the Gulf of Mexico and the Mediterranean Sea. But on a clear day in April 1942, they played a small yet pivotal role in assisting the Doolittle Raiders complete one of the first American aerial attacks of World War II.