Why We Have Norman Van Aken to Thank for the Way We Dine Out Today

The James Beard Award winner tells us, and gives us recipes, about the early days of fusion food

:focal(571x729:572x730)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0f/44/0f447385-ddba-4390-91a0-e2d0e13326bb/no_experience_necessary_mira.jpg)

Prior to the 1980s, the American restaurant scene was dull. French cuisine dominated the menus of the country's best restaurants, reigning supreme for decades, but now the varieties of cuisines are endless, even in France. “The American food scene has changed more in the last 25 years than the last 125,” says multiple James Beard Award winner, cookbook author and radio host Chef Norman Van Aken. It is hard to think that as much a “melting pot,” “salad bowl,” or whatever other food analogy is used to describe this country, it has only been recently that its ethnic cuisines have been embraced by the oppressively high standards of the culinary world.

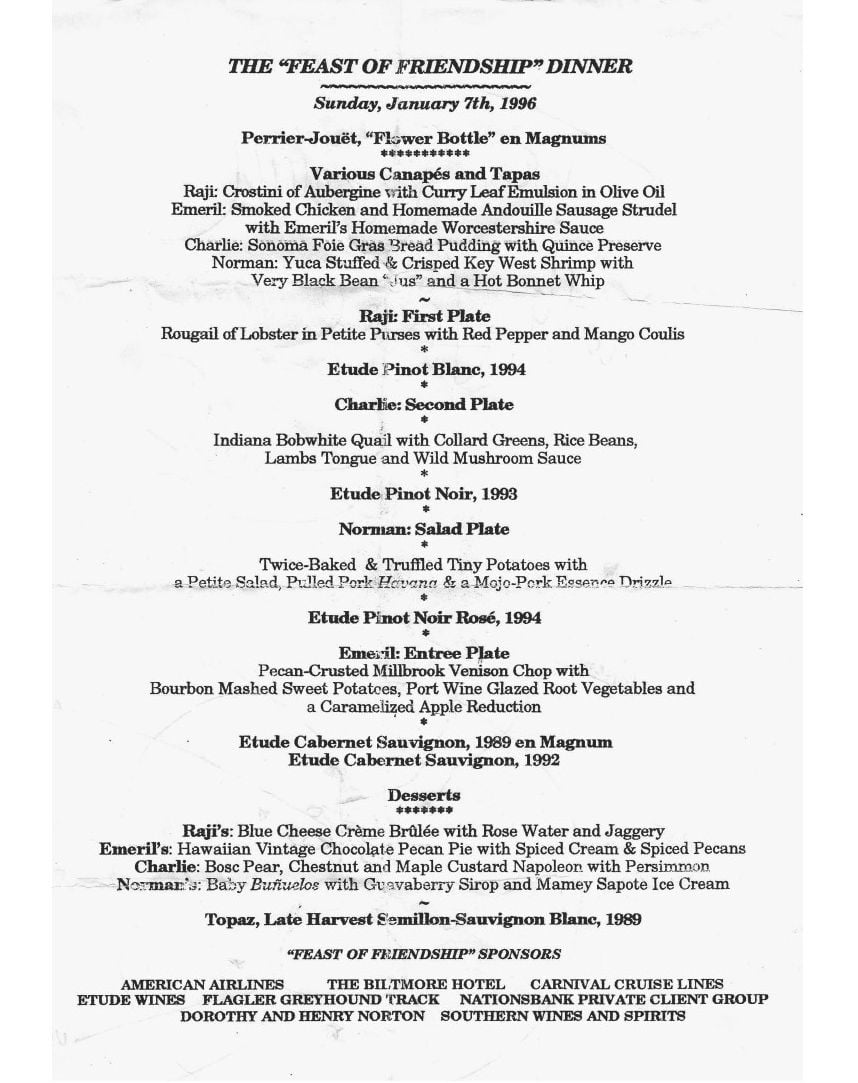

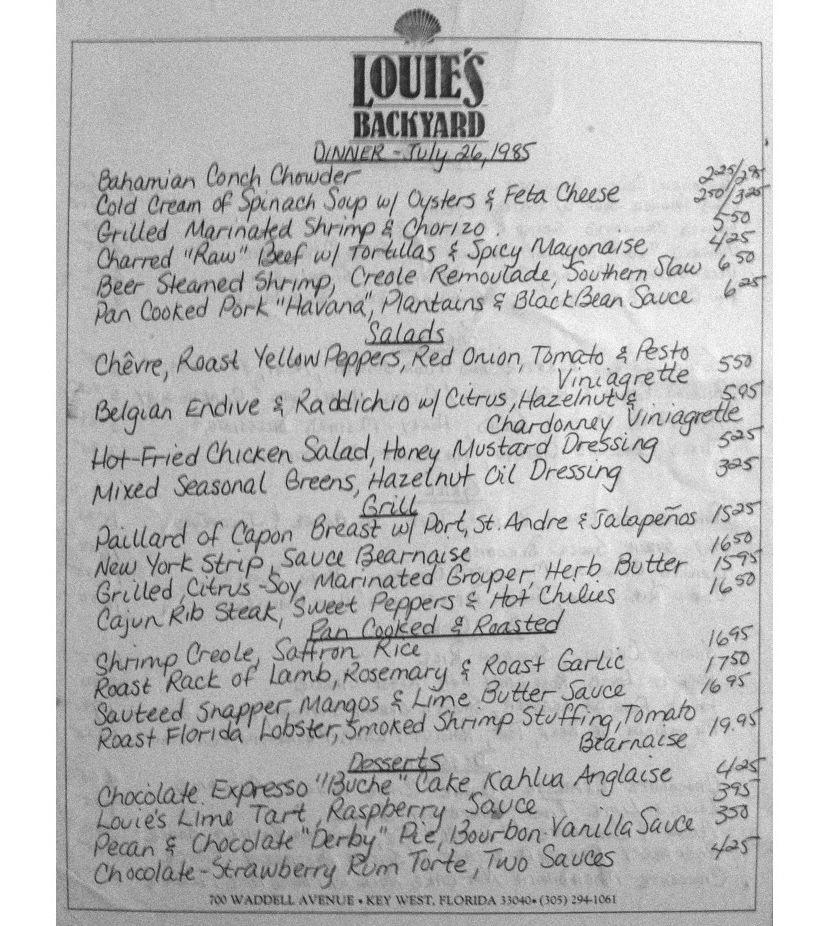

Chef Norman Van Aken is one reason why. Before the celebrity chef craze and before the start of Food Network, Van Aken was starting a revolution. He was doing something unheard of at the time, taking local ethnic flavors, merging them together at restaurants where he worked, the first being Louie's Backyard then his own MIRA. Wolfgang Puck has called him “a true pioneer of the American food movement in the 1980s.” Mario Batali has said, “the American culinary landscape would not be the same without his vision.” And the late James Beard winning chef and restaurateur Charlie Trotter named Van Aken the "Walt Whitman of American cuisine."

During the late '70s and '80s, an exciting shift was taking place in the restaurant scene across much of the United States. Alice Waters was pioneering a cuisine native to California, Mark Miller was showcasing the Southwest's distinguished flavor, Emeril Lagasse was finding his voice in New Orleans, and a young Wolfgang Puck was infusing Asian influences with California ingredients. But Florida and much of the rest of the southeastern United States were at a standstill gastronomically. An area that is so rich in culture and full of history was just stuck in time. The foods of the Latino, Caribbean, Spanish, and African cultures that made up this region were secluded to their own subcultures. Then came Norman Van Aken, a carny, roofer, man-of-many-jobs from northern Illinois, who found his way to the eccentric island of Key West, where he would discover a new cuisine, one that would place him in an exalted group with Alice Waters, Paul Prudhomme and Mark Miller as Founders of New American Cuisine. Van Aken gave a voice to the bright cultures of the southeast in a new free verse.

In his recently published memoir, No Experience Necessary, Van Aken writes about his unconventional journey of becoming a chef and the experiences leading up to the discovery of this American cuisine. In the book, he traces his inspiration back to a moment in western Kansas where Van Aken worked laying concrete. He writes,

“One of the few moments of relief, which provided an almost hallucinatory happiness amid the blind blue of the western Kansas sky, the dull ache of our sledgehammer-shaken limbs, and the desperate hunger of grunt-labor appetites, were the chorizo-and-scrambled-egg-filled tortilla sandwiches the Mexican workers so graciously shared with us. I believe that it is the communal sharing of food in this very rustic way that laid the foundation for me to not only become a chef but to become one who was inspired by the down-to-earth foods of Latino and Caribbean people, and one without a sense that European food is inherently better.”

We sat down with Chef Norman Van Aken to discuss New World cuisine.

How would you define New World Cuisine?

Essentially it is the celebration of the new immigrant cultures that made Florida its home. It’s the coalescence between disparate nations, tongues, religions, backgrounds that have ideocuisine* similar to New Orleans cuisine, but different.

By the 80s, we began to see these pockets of American cuisines that have distinct voices. And it was exciting to notice that America even had a cuisine because we were told by our bosses in the European run kitchens that it didn’t. Being Americans we had a sense that we wanted to be proud too. We wanted to find things too that distinguish us in the same way that France is distinguished comparing the cuisine of Bourdeux vs. the cuisine of Paris. And, I wanted to create a response that was Florida based. I was living in Key West and in Key West you have a very strong rustic, regional, group of voices. And, being not from there, I had no outstanding allegiance to follow one voice versus the other. No one was there to push me in any particular direction, so just like listening to great bands from different backgrounds I was able to sample and fuse what I wished to.

So new world cuisine became a regional cuisine like New Orleans, the Southwest and California.

[* The word ideocuisine is used by Journalist Raymond Sokolov in his book Why We Eat What We Eat: How Columbus Changed the Way the World Eats.]

Why call it New World cuisine?

The term New World Cuisine I chose because of its capacity for breadth. When people began to hyphenate words like Flori-bbean, I said that doesn’t work because if something is coming primarily from Brazil or Argentina there is nothing in "Flori" or "bbean" that incorporates that. And, when Columbus unwittingly bumped into this landmass on his way to what he thought was Asia and India, he discovered unwittingly a new world. It was a seismic shift that’s sometimes called the Columbian exchange. It began to have its ramifications real quickly and began to change the entire planet in the way that we ate.

How did you develop New World cuisine?

I know that I was one of the first persons to take these different dishes, some of the ingredients and put them in a symbiotic relationship, which surprised the people from those specific countries. It was not a point I made with a lot of preconsciousness. I was just responding to the place. If my circumstances had taken me to Fort Lauderdale, Miami, West Palm Beach or Orlando instead of Key West, I don’t think I would have had that raw opportunity of what living in Key West had in the 1970s. There they were just trying to do their mother, father or grandparent’s food. Eating in a Cuban restaurant, Haitian restaurant or Bahamian restaurant and then coming away from those three different things and creating a response to that was my good fortune.

You are also known for coining the word “fusion” cuisine. Is New World cuisine a type of fusion?

New world cuisine is one of the spectrums of fusion cuisine. Fusion cuisine exists everywhere. And has existed everywhere long before a term that I became known for choosing ever came along. People intrinsically take with them what they have, know and love. But, then they are thrust into different circumstances (a war, a marriage) and their adaptation requires them to move forward. That creates a fusion of things.

I think people are wary of fusion cuisine in a way that it can oftentimes be an excessive invention of an overwrought mind. Someone might say, "I am going to put together blueberries and squirrel meat because nobody has ever done it." Maybe there is a reason they’ve never done it. When it is forced and it is done to surprise for the sake of surprise, it becomes something that has little value, if any. Fusion cuisine has existed to me since someone crossed the river and went to the other side. New world cuisine came about sometime during the settling of this particular region of Florida. And like any cuisine whether it is New Orleans cuisine, which moves very slowly in terms of change or what you might call California cuisine, which continues to evolve, and change, fusion cuisine is not restricted to a geographical understanding.

How did you come up with the term fusion (as it relates to cuisine)?

There is a moment where I was reading On Culture and Cuisine [by Jean-Francois Revel] where he is talking about the main thesis of the book. At one point he talks about the dialogue as a “lovers quarrel” that ends in a marriage. And I wrote in a handwritten note on the side of the book “a fusion.” I am sure I said a fusion because of the jazz terminology of fusion. It was me searching for something that was an answer to what I wanted to do with my cooking. And I was determined to go back down historically and figure out the roots of the cuisine from Florida before continental cuisine. To see if I could somehow weld together this power that I felt was there in the DNA but make it understandable to a modern guest. We do have to stay in business at some point, where the guest says, “I agree,” and is willing to come back.

I feel a lot of times in this day and age the chefs have lost that notion all together and are there just to perpetrate their mad genius. I would just as soon go to some really straight forward Brazilian restaurant and eat the soul food [rather] than someone deconstructing a navel orange.

The thing about our dishes is each one of them is its own story. It is something out of a Winesburg Ohio. I have meant there to be a very clear character. It is not about ingredients or the value of a certain ingredient. Additionally, it is a kind of a chemical understanding of the food. What does acidity do? What does fat do? What does meatiness do? And you weave them in such a way that makes them work. Yes, people may not think myrtle berries are an ideal thing to go with foie gras but it can certainly be understood that the acidity of myrtle berries are going to be effective against foie gras the same way grape jelly is effective against peanut butter. But that's one way to look at food, and I call that post historic. You are not really caring that this dish migrated from Italy or Japan. You are just looking at ingredients as if they were on the periodic table and they are going to go together because of the way you put them together. Many chefs do that, not many chefs do it successfully. That’s not enough for me. I want to walk in the steps of history and feel them because I love stories.

How do you see New World cuisine evolving?

New World Cuisine will evolve just like most cuisines have evolved. Through marriage, wars, travel, education, shifting demographics, changes in what is grown and where... all of these. But make no mistake it will happen in a much faster way due to the internet, smart phones etc. As the immigration patterns of North America become more Latin American, this will morph in both obvious and surprising ways. The growing population of Vietnamese in the Gulf region of America will be wed to a migratory Mexican and Central American population I am sure. I can't wait to taste those results...and I hope to jam right alongside!

Recipes reprinted with permission of Taylor Trade Publishing from No Experience Necessary.

Beer-Steamed Shrimp with Mojo Rojo

During the years I was looking for my culinary voice at Louie's Backyard, Janet [Van Aken's wife] was working at the other end of the island at the Half Shell Raw Bar off of Margaret Street at Land's End Village. The voices there belonged to Ron Hatfield and sweet Elayne Culpepper of the Big Coppitt Cowboy Band, who rocked that salty joint for special guests like children's author Shel Silverstein. The Half Shell served their shrimp steamed in beer or fried and served with cocktail or tartar sauce-which I loved then, and love still. For the patrons at Louie's, this was one of my riffs on those simple classics.

For the steamed shrimp:

1 tablespoon allspice berries

1/2 tablespoon black peppercorns

1/2 tablespoon mustard seed

1 teaspoon whole cloves

1 teaspoon fennel seeds

2 bay leaves, torn

4 (12-ounce) bottles of beer

1 lemon, cut into quarters

1 head garlic, cut in half, crosswise

36 large shrimp, still in the shells

Preheat a deep soup pot over medium-high heat. Add the allspice, peppercorns, mustard seed, cloves, fennel seeds and bay leaves; toast about 30 to 60 seconds. Add the beer. Squeeze the lemon quarters over the pot, toss in the squeezed lemon quarters, and add the garlic halves. When the beer comes to a boil, add the shrimp.

When the liquid returns to a boil, the shrimp should be done. Using a colander, drain the shrimp. Place them in a bowl, cover in plastic wrap, and chill in the refrigerator.

Makes 6 to 8 servings

For the Mojo Rojo:

2 red bell peppers

canola oil

6 cloves garlic, minced

1 teaspoon habañero chile, seeds and stems removed, minced

1 teaspoon cumin powder

3/4 teaspoon kosher salt

1/4 teaspoon freshly cracked black pepper, toasted

2 tablespoons sherry vinegar

1/2 cup pure olive oil

2/3 cup mayonnaise

Preheat the oven to 425 degrees F. Lightly rub the bell peppers with canola oil and place on a baking tray. Place the tray in the preheated oven for about 30 minutes, turning the peppers for even color, until well charred. When the peppers are done roasting, remove to a bowl and cover tightly with plastic wrap. Set aside to steam, about 2 minutes. When the peppers' skins are loose, remove and discard the skin, stems and seeds, and blot any liquid from the peppers.

While the peppers are roasting, in a bowl combine the remaining ingredients, except for the olive oil and mayonnaise. Add to the roasted peppers and puree in a blender or food processor, adding the oil at the end. Pulse until the mixture is fairly smooth. Season with additional salt and pepper, if desired. Whisk in the mayonnaise. Cover and store in a cool place until needed.

Makes 2 cups

To serve:

Peel and devein the shrimp; place on a plate or in a bowl with a smaller dipping cup of Mojo Rojo for each guest. Serve with fresh lemon wedges and a bottle of Caribbean hot sauce, if you need more heat.

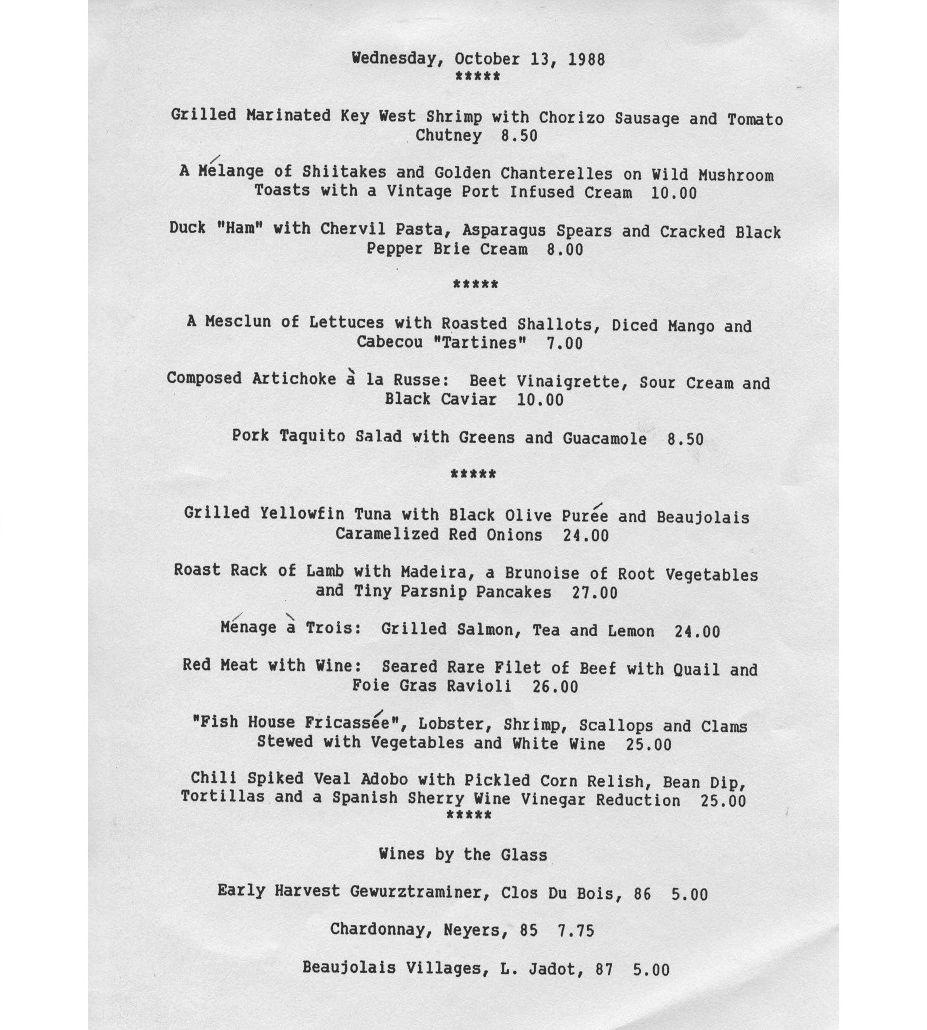

MIRA Tuna Tartare

Various tuna tartare preparations have taken over the world, but back in 1988 it was still pretty fresh territory to many diners in Key West. It was a huge success for us then and continues to be very popular to this day. We called the restaurant MIRA, which means "look" in Spanish, because we wanted our guests to enjoy not only what they could smell and taste, but also to look at each dish and enjoy what they saw. It was while working at MIRA that I wrote the treatise called "Fusion." This dish was an edible example of the very notion.

1/2 pound sushi-quality tuna, diced small

2 tablespoons finely diced onion

1/2 scallion, white part mainly, finely chopped

1 jalapeño pepper, seeds and stems removed, finely minced

1 teaspoon finely minced fresh ginger

1 teaspoon finely minced lemongrass, inner stalks

1/2 teaspoon sesame oil

1 1/2 teaspoons soy sauce

1 teaspoon mirin

1/4 teaspoon rice wine vinegar

1/4 teaspoon fish sauce (optional)

1 teaspoon minced orange zest

1 teaspoon lemon zest

kosher salt and freshly cracked black pepper, to taste

Salsa Sriracha, to taste

In a bowl, combine all the ingredients and chill, tightly covered, until you are ready to serve. There are many ways to present a tartare—I like to serve mine using Asian-style spoons or with sesame seed crackers.

Makes 1 fluid cup

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/shaylyn-headshot.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/shaylyn-headshot.jpg)