A Brief History of the TV Dinner

Thanksgiving’s most unexpected legacy is heating up again

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/69/1669fca7-0243-435c-b63c-55eb6be86f6a/opener.jpg)

In 1925, the Brooklyn-born entrepreneur Clarence Birdseye invented a machine for freezing packaged fish that would revolutionize the storage and preparation of food. Maxson Food Systems of Long Island used Birdseye’s technology, the double-belt freezer, to sell the first complete frozen dinners to airlines in 1945, but plans to offer those meals in supermarkets were canceled after the death of the company’s founder, William L. Maxson. Ultimately, it was the Swanson company that transformed how Americans ate dinner (and lunch)—and it all came about, the story goes, because of Thanksgiving turkey.

According to the most widely accepted account, a Swanson salesman named Gerry Thomas conceived the company’s frozen dinners in late 1953 when he saw that the company had 260 tons of frozen turkey left over after Thanksgiving, sitting in ten refrigerated railroad cars. (The train’s refrigeration worked only when the cars were moving, so Swanson had the trains travel back and forth between its Nebraska headquarters and the East Coast “until panicked executives could figure out what to do,” according to Adweek.) Thomas had the idea to add other holiday staples such as cornbread stuffing and sweet potatoes, and to serve them alongside the bird in frozen, partitioned aluminum trays designed to be heated in the oven. Betty Cronin, Swanson’s bacteriologist, helped the meals succeed with her research into how to heat the meat and vegetables at the same time while killing food-borne germs.

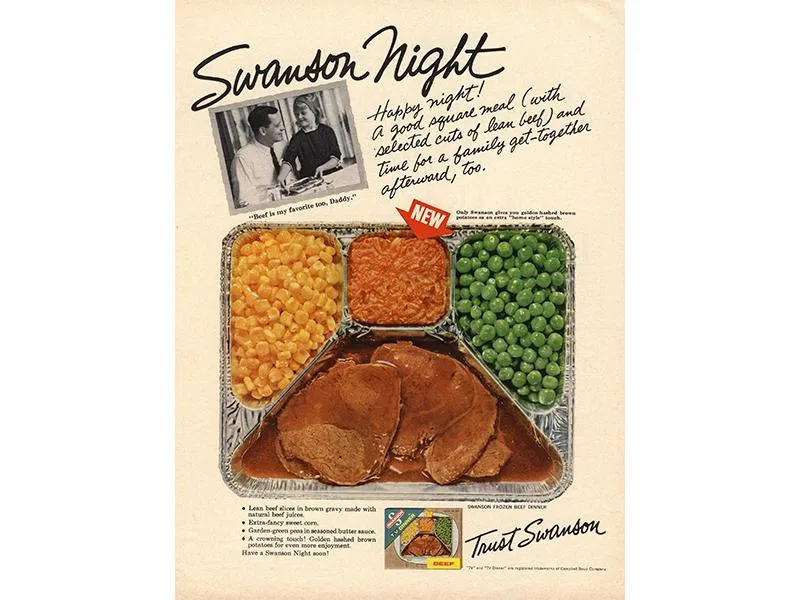

The Swanson company has offered different accounts of this history. Cronin has said that Gilbert and Clarke Swanson, sons of company founder Carl Swanson, came up with the idea for the frozen-meal-on-a-tray, and Clarke Swanson’s heirs, in turn, have disputed Thomas’ claim that he invented it. Whoever provided the spark, this new American convenience was a commercial triumph. In 1954, the first full year of production, Swanson sold ten million trays. Banquet Foods and Morton Frozen Foods soon brought out their own offerings, winning over more and more middle-class households across the country.

Whereas Maxson had called its frozen airline meals “Strato-Plates,” Swanson introduced America to its “TV dinner” (Thomas claims to have invented the name) at a time when the concept was guaranteed to be lucrative: As millions of white women entered the workforce in the early 1950s, Mom was no longer always at home to cook elaborate meals—but now the question of what to eat for dinner had a prepared answer. Some men wrote angry letters to the Swanson company complaining about the loss of home-cooked meals. For many families, though, TV dinners were just the ticket. Pop them in the oven, and 25 minutes later, you could have a full supper while enjoying the new national pastime: television.

In 1950, only 9 percent of U.S. households had television sets—but by 1955, the number had risen to more than 64 percent, and by 1960, to more than 87 percent. Swanson took full advantage of this trend, with TV advertisements that depicted elegant, modern women serving these novel meals to their families, or enjoying one themselves. “The best fried chicken I know comes with a TV dinner,” Barbra Streisand told the New Yorker in 1962.

By the 1970s, competition among the frozen food giants spurred some menu innovation, including such questionable options as Swanson’s take on a “Polynesian Style Dinner,” which doesn’t resemble any meal you will see in Polynesia. Tastemakers, of course, sniffed, like the New York Times food critic who observed in 1977 that TV dinner consumers had no taste. But perhaps that was never the main draw. “In what other way can I get...a single serving of turkey, a portion of dressing...and the potatoes, vegetable and dessert...[for] something like 69 cents?” a Shrewsbury, New Jersey, newspaper quoted one reader as saying. TV dinners had found another niche audience in dieters, who were glad for the built-in portion control.

The next big breakthrough came in 1986, with the Campbell Soup Company’s invention of microwave-safe trays, which cut meal preparation to mere minutes. Yet the ultimate convenience food was now too convenient for some diners, as one columnist lamented: “Progress is wonderful, but I will still miss those steaming, crinkly aluminum TV trays.”

With restaurants closed during Covid-19, Americans are again snapping up frozen meals, spending nearly 50 percent more on them in April 2020 over April 2019, says the American Frozen Food Institute. Specialty stores like Williams Sonoma now stock gourmet TV dinners. Ipsa Provisions, a high-end frozen-food company launched this past February in New York, specializes in “artisanal frozen dishes for a civilized meal any night of the week”—a slogan right out of the 1950s. Restaurants from Detroit to Colorado Springs to Los Angeles are offering frozen versions of their dishes for carryout, a practice that some experts predict will continue beyond the pandemic. To many Americans, the TV dinner tastes like nostalgia; to others, it still tastes like the future.

Vintage Takeout

Grab-and-go meals might be all the rage, but the ancients also craved convenience —Courtney Sexton

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sexton_Remy.jpg)