Welcome to Rawda

Iraqi artists find freedom of expression at this Syrian café

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/rawda2.jpg)

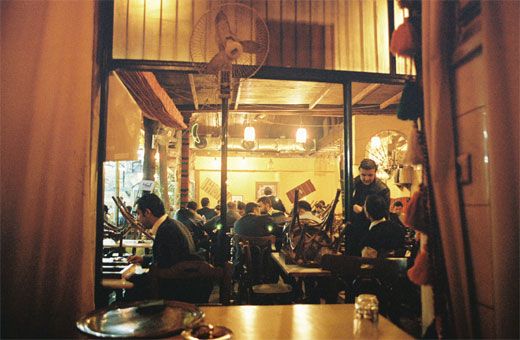

It's 8 p.m. on a Friday night at Rawda, a coffee house in the Al Sahin district of Damascus, Syria, and the regulars are filing in. They occupy chairs and tables under languid ceiling fans and a haphazardly joined ceiling of corrugated plastic sheets. Water pipes are summoned, primed and ignited, and soon the din of conversation is dueling with the clatter of dice skittering across backgammon boards.

Once a movie theater, Rawda is an enclave for artists and intellectuals in a country where dissent is regularly smothered in its crib. Lately, it has become a bosom for the dispossessed. The war in Iraq has triggered a mass exodus of refugees to neighboring Syria, and Rawda plays hosts to a growing number of them. Most are artists, orphaned by a conflict that has outlawed art.

"We can no longer work in Iraq," says Haidar Hilou, an award-winning screenwriter. "It is a nation of people with guns drawn against each other. I can't even take my son to the movies."

Some two million Iraqis have fled the sectarian violence in Iraq. They are Sunnis driven out by Shiite militias and Shias threatened by the Sunni insurgency. They include some of the country's most accomplished professionals—doctors, engineers and educators—targets in the militants' assault on the Iraqi economy.

But there is another war in Iraq, one on artistic expression and critical thought. Among the exiles slumping their way to Damascus are writers, painters, sculptors, musicians and filmmakers, who are as important to Iraq's national fiber as its white-collar elites. Rawda, which means "garden" in Arabic and was itself founded by Russian émigrés before World War II, has become their smoke-filled sanctuary.

"People from all walks of life come here," says dissident Abu Halou, who left Baghdad in the 1970s and is now the unofficial "mayor" of Syria's Iraqi diaspora. He says the owners were once offered several million U.S. dollars in Syrian pounds by a developer who wanted to turn Rawda into a shopping mall. "They turned him down," Abu Halou says, seated as always at the main entrance, where he appraises all new comers. "The family understands how important this place is to the community."

For the Iraqis, Rawda is a refuge of secularism and modernity against pathological intolerance back home. They swap tales, like the one about the Baghdadi ice merchant who was attacked for selling something that did not exist during the time of the Prophet, or the one about the motorist who was shot by a militant for carrying a spare tire—a precaution that, for the killer, betrayed an unacceptable lack of faith. In Syria, at least, the art colonists of Rawda can hone their skills while the sectarian holocaust rages next door.

"The militants believe art is taboo," says Bassam Hammad, a 34-year-old sculptor. "At least here, we can preserve the spirit of Iraq, the smells of the place. Then maybe a new school can emerge."

After the fall of Saddam Hussein, Hammad says he was cautiously optimistic about the future. But as the insurgency grew in intensity, so did proscriptions against secular expression. Liquor stores were torched, women were drenched with acid for not wearing the veil and art of any kind was declared blasphemous. In July 2005, Hammad was commissioned by a Baghdad municipal council to create a statue that would honor 35 children who were killed in a car bombing. It was destroyed by militants within two months, he says.

Though Hammad turned down two more such commissions, he began receiving death threats taped to the door of his home. He remained locked indoors for five months before he abandoned Iraq for Syria. "They made me a prisoner in my home," he says. "So I came here."

Iraq was once legendary for its pampered bourgeoisie, and its artists were no exception. Just as Saddam Hussein, a frustrated painter who fancied himself an adept playwright, subsidized Iraq's professional classes, he also gave its painters, musicians and sculptors generous stipends. They were allowed to keep whatever money they could make selling their work, tax-free, and the state would often buy what was left over from gallery exhibitions. Like athletes from the old Soviet Union, young students were tested for artistic aptitude and the brightest ones were given scholarships to study art and design, including at the Saddam Center for the Arts, Mesopotamia's own Sorbonne. Iraqi art festivals would attract artists from all over the Middle East.

In a surreal counterpoint worthy of a Dali landscape, Baghdad under Saddam was a hothouse for aestheticism and culture. "It was so easy to be an artist then," says Shakr Al Alousi, a painter who left Baghdad after his house was destroyed during an American bombing raid. "It was a golden age for us, providing you stayed away from politics."

Filmmaker Ziad Turki and some friends enter Rawda and take their positions in one of the naves that abut the main courtyard. At 43, Turki was born too late to experience modern Iraq's artistic apex. A veteran of several battles during the Iraq-Iran war, he remembers only the deprivation of the embargo that was imposed on Iraq following its 1990 invasion of Kuwait. Turki studied cinematography at the Art Academy of Baghdad and after graduating made a series of short films with friends, including Haider Hilou.

In July 2003, they began producing a movie about the U.S. invasion and the insurgency that followed. They used rolls of 35-millimeter Kodak film that was 22 years older than its expiration date and shot it with a borrowed camera. Whenever firefights erupted and car bombs exploded, says Turki, the crew would grab their gear and compete with news teams for footage. Everyone on the project was a volunteer, and only two of the players had any acting experience. Post-production work took place in Germany with the help of an Iraqi friend who was studying there.

Turki called his movie Underexposed. "It's about what is going on inside all Iraqis," he says, "the pain and anguish no one ever sees." The film cost $32,000 to make and it won the 2005 award for best Asian feature film at the Singapore International Film Festival. (Critics hailed the production's realistic, granular feel, says Turki, which he attributes to that outdated Kodak film.)

Syria once had a thriving movie industry, but it was claimed decades ago by cycles of war and autocracy. There is little for a filmmaker to do in Damascus, even celebrated ones like Turki and Hilou. They are currently producing short documentaries about refugees, if nothing else, to lubricate their skills. Turki draws inspiration from Francis Ford Coppola but models himself on the great Italian directors like Federico Felinni and Luigi Comencini, who could finesse powerful emotions from small, austere films. "As a third-world country, we will never make high-tech blockbusters," Turki says between tokes from a water pipe. "Our movies will be simple, spare. The point is that they be powerful and truthful."

Turki fled Iraq in November 2006 after militant set fire to his home. Like his fellow émigrés, he is grateful to Syria for allowing him in. (Neighboring Jordan, also home to about a million Iraqi exiles, is turning many away at the border.) But he's not sure where he'll end up. "Frankly, I don't know where I'll be tomorrow," he says.

Tonight at least, there is Rawda, proudly anachronistic, an old-world coffee house in one of the planet's final Starbucks-free frontiers. It may seem strange that refugee artists would find asylum in an authoritarian state like Syria, but perversity is one of the Arab world's most abundant resource these days. A war that was waged, retroactively at least, in the name of liberty and peace has made a neighboring autocracy look like an oasis.

"Art requires freedom of expression," says Hammad, the sculptor. "If we can't have it in Iraq, then at least we can create art in exile."

Stephen J. Glain is a Washington, D.C.-based contributing editor to Newsweek International.