Is Champagne Still Champagne Without Bubbles?

In a storied part of France, a group of artisan producers is making this beloved wine the old fashioned way—sans fizz

:focal(351x192:352x193)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/db/fe/dbfe3703-9bd8-4f89-bcea-72ef32c47a22/elodie-and-bernadette-marion-champagne0517.jpg)

This story originally appeared on Travel + Leisure.

“I can't stand bubbles,” announced Cédric Bouchard, a handsome winemaker who looks more like an indie rocker than the producer of some of the most rarefied champagnes in the world. Bouchard talks quickly and has a lot to say — much of it expressed in a rural French version of skater slang. As we stood sampling his wines in the frigid cellars beneath his home in Landreville, in southern Champagne, he decreed the delicate pearlescence in one of his experimental cuvées to be vachement monstre, quoi" — the Gallic equivalent of “totally gnarly.” This was a good thing, bien sûr.

Bubbles may be Bouchard’s pet peeve, but he’s been finding radical ways to discreetly incorporate them into his wines. His hallmark is a gently elegant spritziness, as opposed to the Perrier-level carbonation found in many commercial sparklers.

“Big bubbles are way too present in most champagne,” Bouchard continued. “I hate it when you get a bottle with that expansive, nasty mousse. There is no other word for it: I detest bubbles.”

Champagne, a vast region roughly an hour and a half east of Paris, has long been dominated by multinational luxury brands that sell industrially made fizz. In fact, these big houses have cornered more than 70 percent of the market, buying up grapes from vintners all over the region. Now a new generation of récoltants-manipulants (the private farmers who cultivate and keep their own grapes) is rediscovering the area’s little-known heritage of still wines. Like Bouchard, these artisan producers are creating soulful, homegrown, and, yes, sometimes bubble-free champagnes that are increasingly in demand.

Few people outside France have ever tried a sparkle-free wine from Champagne, but these still wines, known as Coteaux Champenois, aren’t hard to find locally. You can even buy them at the Autogrill rest stops on the highway that runs through the region. Unfortunately, they are rarely exported. So for wine lovers like me, part of the allure of visiting Champagne is the opportunity to sample these non-bubbly treasures.

In the time it took me to finish half a glass of Bouchard’s rosé champagne, its effervescence (which began as a very fine bead) had dissipated entirely. “That’s exactly it!” he explained, excitedly. “I like it when the bubbles are there at the beginning, in a subtle, silky way — and then, before you empty your glass, they vanish! This allows you to see that what you are drinking is truly a vin de Champagne: a wine from Champagne.”

Bouchard is adamant that his wines, like all great ones, are capable of transmitting terroir and the nuance of individual vintages. This notion is in direct opposition to the way major brands standardize their wines, creating blends of different years so that their nonvintage bottlings always taste identical. While some champagnes by the luxury brands are excellent, this isn’t necessarily true of their entry-level offerings, which account for the vast majority of champagne consumed around the world.

Bouchard’s pursuit of finessed, less bubbly wines actually dates back to an earlier era of wine making in Champagne. In fact, Louis XIV’s favorite drink was non mousseux wine from Champagne. Bubbles were considered a fault in wines until the 18th century.

The legend goes that Dom Pérignon, a monk at the St.-Pierre d’Hautvillers abbey, invented sparkling champagne by accident. “Come quickly, I am tasting the stars!” he exclaimed. The truth is that Pérignon was actually more concerned with preventing bubbles from forming, as they tend to do in this cold climate.

Champagne is a chilly place, even in springtime. Upon my arrival, I noticed that everybody was wearing scarves. The region’s famed underground cellars, so vast that you can ride trains through the labyrinthine tunnels, are frigid year-round. Champagne is, after all, the northernmost viticultural region in France. And according to Bouchard, a frosty cellar is one of the key factors in securing the ultralight bubbles he favors in his wines — alongside low-pressure bottling and not dosing it with added sugar.

**********

Bérêche et Fils, in the hamlet of Ludes, is a prime source for bubbleless Coteaux Champenois, as well as sparkling champagnes. “I want to showcase the fact that we make wine first and bubbles second — and to give people a sense of our terroir,” explained Raphaël Bérêche as he walked me through his family’s winery. Like Bouchard, Bérêche is one of the region’s younger vintners. Bérêche’s operation is bigger than Bouchard’s, but an emphasis on precision and purity can be seen in all of the family’s cuvées, from their various excellent sparklers to their red and white Coteaux Champenois. “The challenge is to prove that still wine deserves to be made again in Champagne,” he said.

His red Coteaux Champenois is proof enough, as I discovered when he opened a bottle of his Ormes Rouge Les Montées. The wine is a refreshingly light-bodied Pinot Noir blend with notes of spices and strawberries. His white Coteaux Champenois is just as good, with more than a passing resemblance to white Burgundy. As we tasted, he showed me an old advertisement for his family’s 1928 and 1929 vintages, including "Vin Brut de Champagne non Mousseux.” It was yet another reminder that still wines aren’t novelties here.

That non-fizzy champagne has such a long, if largely forgotten, history is part of the reason this region is returning to its roots. The one snag with Coteaux Champenois is that it needs to be grown on the best, sunniest slopes — premium real estate. As a result, still wines can end up costing as much as high-end bubbly champagne. “There really isn’t a huge market for these still wines,” Bérêche admitted, “but that’s not the point. The point is to show what our landscape is capable of. Plus, like mousseux champagne, it’s really good with food.”

Many of the restaurants in and around Reims, the region’s largest city, are now showcasing these still wines along with the traditional champagnes. The Michelin three-starred restaurant in the Assiette Champenoise hotel offers more than 1,000 different champagnes (with all levels of bubbliness) to pair with its particularly haute cuisine: truffles, langoustines, foie gras, and sea urchin. Rich food like this needs soaring acidity — which you find both in champagne and in Coteaux Champenois.

Nearby, at Racine restaurant, where Japanese chef Kazuyuki Tanaka prepares refined, artful dishes, the sommelier recommended I try a glass of Mouzon Leroux’s L’Atavique champagne with the deconstructed flower-scallop-cucumber dish I was eating. The bottle’s label explained its philosophy: “Atavism: the reappearance, in a descendant, of characteristics that belonged to an ancestor.” This was a champagne made with the very intention to keep alive the qualities of champagne from the past — and it paired spectacularly well with my meal. It was simultaneously old-fashioned and forward-thinking, as earthy as it was elevated.

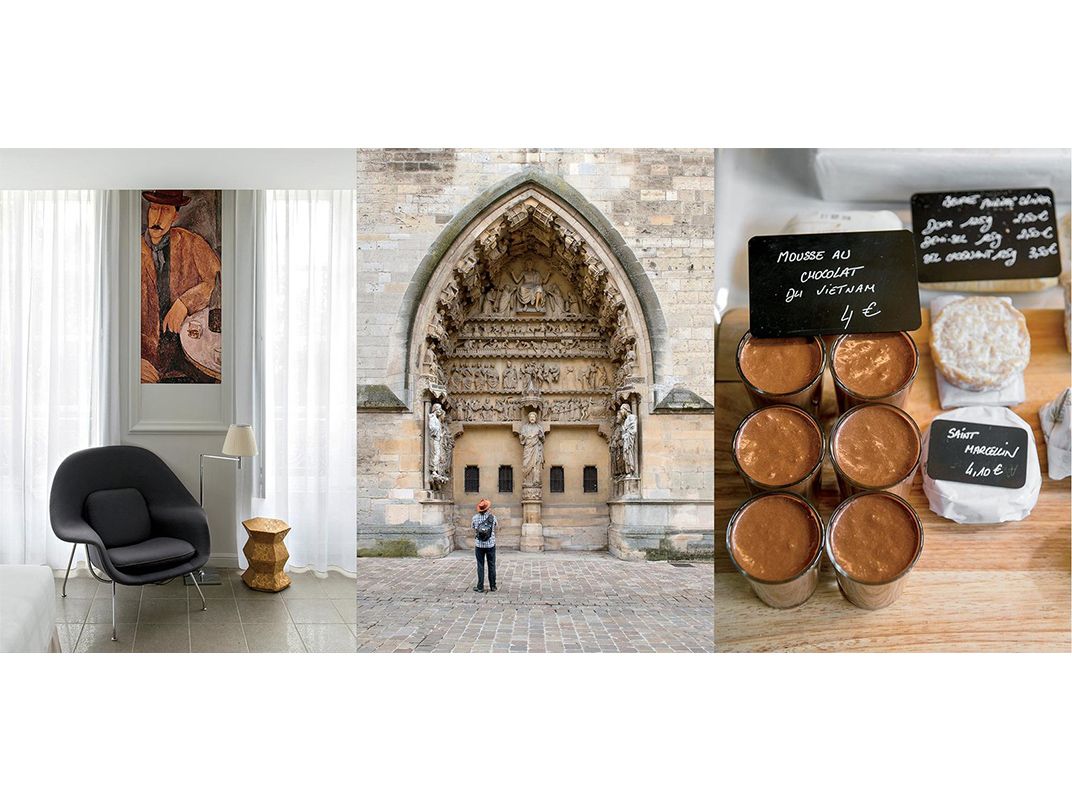

“I don’t offer any of the grandes marques here,” explained Aline Serva, the stylish owner of L’Épicerie au Bon Manger, referring to the big brands of champagne. Her grocery store has several tables where you can sit and wash down smoked salmon, Basque charcuterie, and sustainably farmed caviar with a bottle of Coteaux Champenois from her well-curated selection. Serva also highlights a number of women-run Champagne domaines in her selections — a natural choice, since Champagne today has a strong female wine-making presence, including producers such as Marie-Noëlle Ledru, Marie-Courtin, and Marion-Bosser.

**********

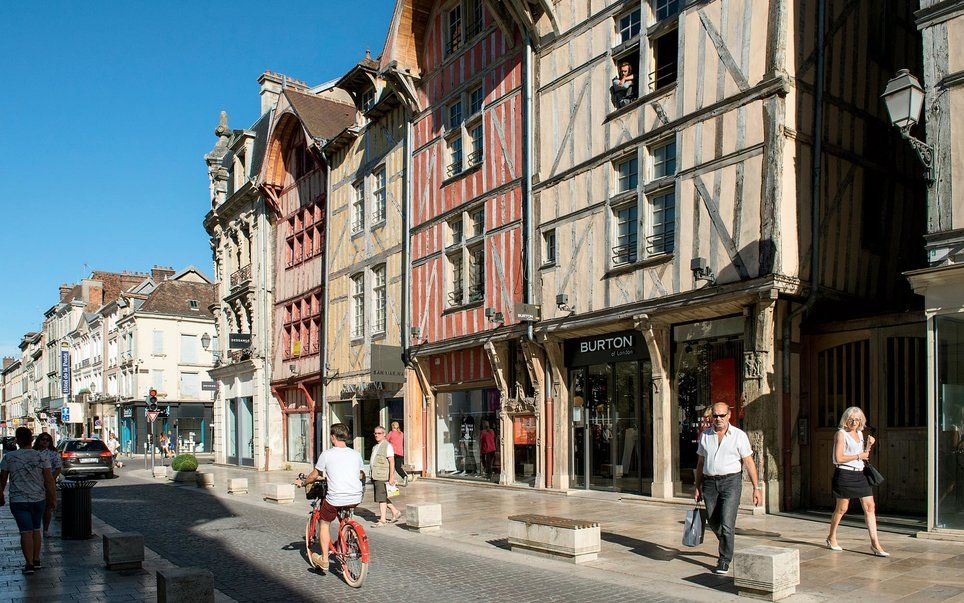

Many young winemakers hang out at Aux Crieurs de Vin, in Troyes, which is an hour and a half south of Reims, not far from Bouchard’s vineyards. Once the region’s prosperous capital, Troyes has stayed delightfully stuck in time, filled with slanting, centuries-old, half-timbered houses, giving it the feel of a Shakespearean set. Aux Crieurs de Vin specializes in no-frills French-country cuisine in a historic building in the center of town. The front section is a wine store where you can pick up a bottle of natural wine, like a Savart or a Jacques Lassaigne, to drink with your andouillette or roasted lamb in the back dining room.

Vincent Laval, who makes wine under his father’s name, Georges Laval, is one of the region’s elder statesmen. His family has been growing grapes here since at least 1694, and his father is seen as a pioneer in organic viticulture. When I visited his winery in Cumières, a village not far from Dom Pérignon’s abbey, Laval, bearded and burly, greeted me. He was eager to show me the intricacies of making his various wines and champagnes. He pointed out two kinds of vine root systems planted on the walls of his cellar. On one side were vines that had been treated with pesticides and synthetic fertilizers. Their roots were shallow, growing horizontally across the top of the soil. Next to them were vines grown organically, with roots that grew vertically, deep into the ground, in search of nutrients. “This method may produce more grapes,” he conceded, pointing at the shallow roots. “But these grapes,” he turned back to the organic roots, “have a more pronounced minerality, a greater aromatic complexity, a much stronger depth of flavor.”

He offered me some of that year’s vin clair, the freshly fermented wine destined to become champagne after undergoing the méthode champenoise to add bubbles. These still wines are different from Coteaux Champenois in the sense that they aren’t a final product. They tasted luminous, with a haunting floral perfume, somewhere between jasmine blossoms and wild irises. Vin clair transmits the essence of Champagne’s terroir, Laval explained. It’s a reminder that real champagne is an elemental thing, a gift of the soil tilled by actual craftspeople as opposed to a product necessarily destined to be marketed as a luxury good.

As good as his vin clair was, Laval stressed that it was not a finished wine. “It is still taking its form,” he explained. “And it becomes even better with bubbles. After all, bubbles are what we are!” Laval makes small quantities of all his different wines and champagnes — around 10,000 bottles a year, as compared with the 26 million bottles Moët & Chandon produces annually. And he makes his red Coteaux Champenois only in certain years. The one I was lucky enough to try had a lovely, slightly tannic, cherry-juice quality.

Like Laval, Domaine Jacques Selosse is renowned for the rarity — and the quality — of its bottlings. This maison is run today by sixty-something legend Anselme Selosse, a central figure in the viticultural revolution, whose wines fetch significant sums. Selosse makes a wide variety of champagne at his cellar in Avize. (It’s a family operation: his son, Guillaume, works with him at the winery while his wife, Corinne, helps run a small, elegant hotel inside the château.) A tasting here is an opportunity to experience everything that Champagne’s terroir is capable of — specific parcels, vintages, blends, and styles. Selosse surprised me by mentioning that he even makes a Coteaux Champenois, although he does it in such small batches that he ends up giving most of his bottles as gifts to friends and family.

“Our whole aim is to highlight where our wines are made,” Selosse said. “What is champagne? It is a wine from Champagne. You need to be able to taste where it is from, which means it shouldn’t be insipid or neutral. When you get a sparkling wine made by a technician you can’t tell where it was made.”

Selosse has the ability to explain Champagne’s complexities in simple terms. “The idea of terroir exists all over the whole planet,” he said as songbirds chirped away in the background. “The United States, for example, has barbecue culture. I always tell Americans to think of barbecue as a way to explain what’s happening here in Champagne. Sunday barbecue has an ambience around it, a ceremonial aspect, a way of doing it. The sauces and the rubs and the methods of marinating or smoking differ from state to state and from region to region and even from producer to producer. The same thing applies with champagne.”

Although Selosse doesn’t sell Coteaux Champenois wines — he says they’d be too expensive — I was ecstatic to taste his red wine, the Lubie rouge, when I visited. As soon as I tried it, I could tell that it is what wine used to be in Champagne: a wine for kings. It had a sensationally floral bouquet: a combination of rose, raspberry, and lychee. It was a glimpse into the past, yet as I tasted it, I also felt like I could see a future in which bubbleless champagne could become as important as it once was.

“A bubble is, in effect, a defect — but what a remarkable defect it is,” Selosse pointed out. “It’s a fault that became an accessory. And now that accident is part of the texture of our wines. It’s an espuma in the mouth, like a pillow your taste buds recline on. It’s something that gives consistency. And really, we don’t have the choice: our identity is in the bubbles.”

**********

The Details: What to Do in Today's Champagne

Hotels

Hôtel Les Avisés: A renovated 10-room château in the heart of the Côte des Blancs. Its restaurant serves traditional dishes and features an extensive wine list curated by legendary winemaker Anselme Selosse. Avize; selosse-lesavises.com; doubles from $268.

La Maison de Rhodes: This hotel is housed in a centuries-old architectural marvel and has a lovely medieval garden just a few blocks from the cathedral in Troyes. maisonderhodes.com; doubles from $224.

L’Assiette Champenoise: This property on the outskirts of Reims is popular for its Michelin-three-starred restaurant. Tinqueux; assiettechampenoise.com; doubles from $199.

Restaurants

Aux Crieurs de Vin: A natural-wine bar known for its fantastic country cooking and store stocked with plenty of organic champagnes and other French varietals. If you see a bottle of Jacques Lassaigne’s white Coteaux Champenois, get it. Troyes; auxcrieursdevin.fr.

Glue Pot: This pub is among the best places in the region to get classic bistro fare. Reims; fb.com/glue.pot; prix fixe from $13.

La Gare: This restaurant inside a former railway station in the village of Le Mesnil-sur-Oger is run by wine-making estate Robert Moncuit. Its bistro cooking is as good as its blanc de blancs. lagarelemesnil.com; prix fixe $28.

L’Épicerie au Bon Manger: Stock up on groceries and the finest artisanal champagnes after grabbing a bite to eat at Aline and Eric Serva’s store. Reims; aubonmanger.fr.

Racine: To experience thefull range of Kazuyuki Tanaka’s meticulously composed dishes, go for the $100 “Daisuki” tasting menu. racine.re; tasting menus from $75.

Wineries

Bérêche et Fils: This family-owned company’s domaine in Ludes, in the Montagne de Reims region, can be visited on Fridays at 10:30 a.m. and 4 p.m. by appointment. bereche.com.

Champagne Georges Laval: This popular domaine sits on a tiny side street in Cumières. It produces only a limited number of bottles of Coteaux Champenois a year, so make sure to snag one while you’re there. georgeslaval.fr.

Champagne Marion-Bosser: Situated next to Dom Pérignon’s abbey in Hautvillers, this domaine has a simple two-bedroom apartment available for rent by the night. champagnemarionbosser.fr.

Jacques Selosse: To do a tasting here, guests must stay at the owner’s hotel, Les Avisés, and prebook a spot at one of Anselme Selosse’s VIP tastings, which cost $32 per person and are held at 6 p.m. on Mondays and Thursdays and 11 a.m. on Saturdays. selosse-lesavises.com.

Other articles from Travel + Leisure: