How the Silk Road Created the Modern Apple

A genetic study shows how wild Kazakhstan apples dispersed by traders combined with other wild species to create today’s popular fruit

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/36/ee36eaf7-93fe-4990-9c74-9bcd54dc519d/apples.jpg)

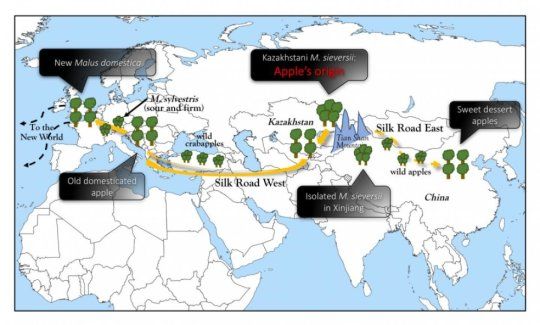

The Silk Road, the famed network of trade routes that connected China with central Asia, India, the Middle East, Turkey and Europe between 130 B.C. and 1453 A.D., was crucial for spreading technology, knowledge, political ideas and luxury goods (and a little disease as well). Now, new research shows there's something else to thank the Silk Road for: it was instrumental in the development of the modern apple, reports Nicola Davis at The Guardian.

In 2010, researchers sequencing the genome of the domestic apple, Malus Domestica found the fruit was incredibly complex with about 57,000 genes—the highest of any plant genome studied thus far. Humans, by comparison, have 19,000 genes. The studied also revealed that the primary ancestor of the domestic is a wild species, Malus sieversii. For the new study, published last week in the journal Nature Communications, researchers dove deeper into the genetic data to suss out the origin story of the cultivated apple.

According to a press release, researchers from the United States and China sequenced the genomes of 117 apples, including domestic varieties as well as crab apples and wild apples from 24 different species. They then compared the genomes to unravel the story of how all those species combined to create today’s Granny Smiths and Honeycrisps. As the researchers found, the Silk Road was an integral part of that development.

Davis reports that researchers discovered two distinct populations of Malus sieversii exist—one in the Xinjiang area of China and the other growing to the west of the Tian Shan mountains in Kazakhstan. However, the genetic data also revealed that modern cultivated apples only developed from the Malus sieversii native Kazakhstan. As traders on the Silk Road traveling to the West ate these apples, they either planted their seeds deliberately or tossed their cores onto the roadside. The apple trees that resulted cross-pollinated with local species of crabapple. The sieversii genes made these apples large and appealing, while the crab-apple genes made the flesh firmer and the taste more sour.

At the same time, Kazakhstan apples headed east as well, cross-breeding with other species, which resulted in the soft, sweet dessert apples found today in China. “The traders go across the Eurasian continent both ways,” study co-author Yang Bai, of the Boyce Thompson Institute at Cornell University, tells Davis. “They spread those ancestral seeds along their way.”

Eventually, humans began to deliberately breed apples for certain flavors and traits, leading to 7,500 types of apples, some best for baking, some great for making cider and some perfect just for chomping.

The analysis reveals that about 46 percent of the domestic apple genome comes from the Kazakhstan population of the Malus sieversii, while 21 percent comes from the European crabapple, Malus sylvestris; the other 33 percent of the domestic apple's genome comes from uncertain origins.

According to the press release, while the modern apple may contain more genomes from Malus sieversii, they are nevertheless much more similar in flavor and texture to crab apples than to their Kazakh foreapples. “For the ancestral species, Malus sieversii, the fruits are generally much larger than other wild apples. They are also soft and have a very plain flavor that people don't like much,” Bai says.

Having the genomes of so many apples will help apple breeders figure out how to produce larger, juicier, insect and disease-resistant apples more quickly. Davis reports the discovery that the Xinjiang population of Malus sieversii has not been subjected to domestication means those apples may hold a reservoir of traits that could also help improve domestic apples. “Those apples are not getting involved in any of the domestic apples – they are a lost jewel hidden there in the Xinjiang area,” Bai says.

The study will also help researchers target genes that help improve the size of apples. While it’s still years away, Bai says in the press release that in the wildest scenario breeders may be able to produce apples the size of watermelons. Which, might lead to a future full of much larger pies.