How the Public Helped Historians Better Understand What Happened at Tulsa

A century after the massacre of a prosperous Black community, Smithsonian volunteers transcribed nearly 500 pages of vital records in less than 24 hours

:focal(400x240:401x241)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ed/42/ed4254a9-90e4-442f-bceb-fbdaffadb42b/nmaahc-2013_79_14c_001.jpeg)

In 1921, as May turned to June, a white mob descended on Greenwood, a prosperous African American neighborhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and killed at many as 300 people. The attack—known today as the Tulsa Race Massacre—left an additional 10,000 Black people unhoused and dozens of neighborhood churches, newspaper offices and businesses burned to the ground.

City officials and law enforcement papered over the massacre for decades. Historians all but wrote it out of Oklahoman and national history. But the truth was recorded nonetheless: In first-person accounts, interviews, photos, scrapbooks and more, Black Tulsans related scenes of graphic violence, unimaginable loss and the devastating impacts of the attack on the once-thriving Greenwood district.

Today, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) holds many of these critical primary documents in its collections. On May 17, ahead of the centennial of the massacre, the museum and the Smithsonian’s Transcription Center announced a call for volunteers to help transcribe a core selection of artifacts through an online portal.

To organizers’ surprise, volunteers responded with overwhelming enthusiasm, completing the work—including the transcription of nearly 500 pages of primary documents—in less than 24 hours. What’s more, 137 individuals who had never worked on NMAAHC transcription projects before joined the effort.

To learn more about the history of the Tulsa Race Massacre, related collections from @nmaahc, and the role that transcription plays in reparative and restorative justice work, join us for a discussion with @nmaahc Curator, Dr. Paul Gardullo, on 5/24. https://t.co/ydq71Jajvq pic.twitter.com/Etu3MEOuUr

— Smithsonian Transcription Center (@TranscribeSI) May 17, 2021

The outpouring of support for the Tulsa transcription project is “heartening,” says Paul Gardullo, a curator at NMAAHC and the director of the Center for the Study of Global Slavery.

“I didn’t even have time to repost the social media thread [calling for volunteers] before learning that the work was complete,” he adds in an email to Smithsonian magazine. (Gardullo is hosting a free Zoom webinar on the project next Monday, May 24, at 1 p.m. EST.)

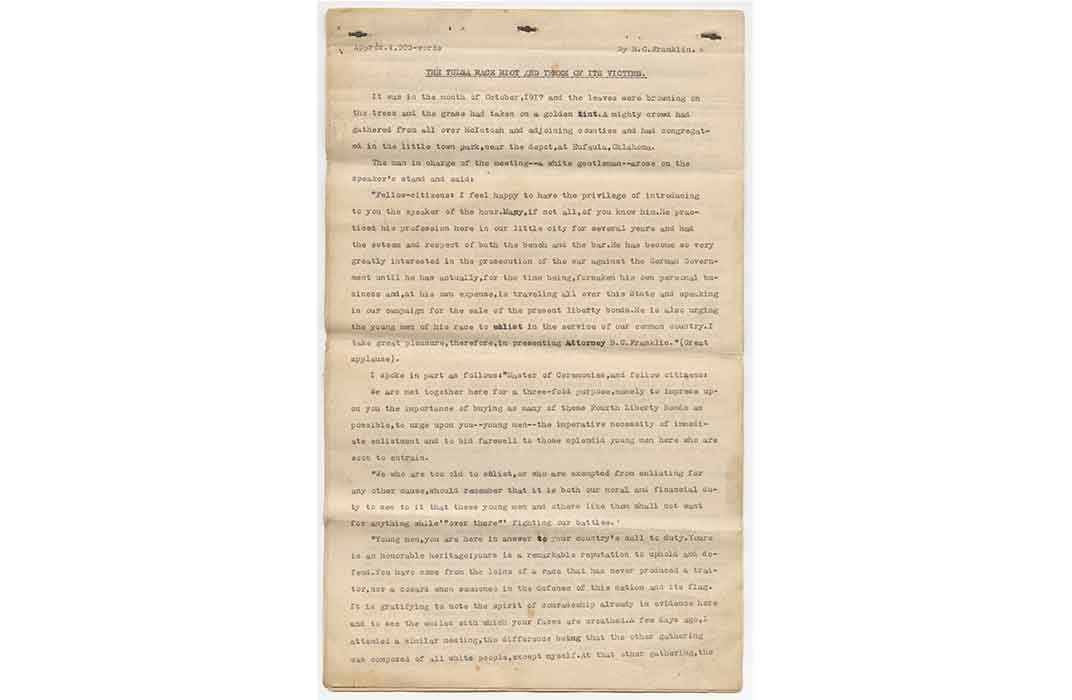

Transcription allows curators and archivists to make valuable primary documents searchable, accessible and readable to countless online users. For this project, the museum asked transcribers to pore through four collections related to the massacre, including an unpublished manuscript by Buck Colbert “B.C.” Franklin (1879–1960), a Black attorney whose home and office were destroyed by the 1921 mob.

In the immediate aftermath of the massacre, Franklin worked out of a tent, fighting racist zoning laws that were designed to prevent Tulsa’s Black residents from rebuilding their homes. He typed this manuscript on the occasion of the massacre’s ten-year anniversary, recording a “searing” eyewitness account of the violence, as Allison Keyes wrote for Smithsonian in 2016.

Other artifacts transcribed by volunteers include the papers of William Danforth “W.D.” Williams, who was a high school student in 1921. His parents owned the iconic Dreamland Theatre and several other Greenwood businesses, all of which were destroyed during the massacre.

Williams’ scrapbooks and records from his long career as a public school teacher speak to the enduring grief that he and his family suffered in the wake of the massacre, as well as the Black community’s resilience in the face of devastation.

“They are the kind of personal materials that humanize this history of violence, trauma and resilience,” Gardullo says.

The curator adds that NMAAHC also houses one of the biggest collections of oral histories related to the massacre. He hopes these holdings will be added to the transcription portal in the future.

For those interested in studying more primary resources related to the massacre, Gardullo points to Tulsa’s Gilcrease Museum, which recently acquired an archive of oral history material collected by Eddie Faye Gates, the longtime chair of the survivors committee of the Tulsa Race Riot Commission.

Transcribing these records can be emotionally exhausting. Readers should note that the collections contain references to racial violence, offensive terminology, and descriptions of assault and trauma. The center encourages anyone reading through the documents to “engage at the level in which they are comfortable.”

The evidence contained in these archives will shape ongoing conversations about long-sought reparations for massacre victims. Per Amy Slanchik of News on 6, the City of Tulsa is currently conducting archaeological work at the suspected site of a mass grave first discovered in late 2020.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/1c/0d1c3176-ee3f-4e0a-a18f-84dffb899ac9/tulsaraceriot1921-residentialblocksburneddown.jpeg)

On Wednesday, 107-year-old survivor Viola Fletcher—who was just 7 at the time of the massacre—testified before Congress as one of the lead plaintiffs in a reparations lawsuit filed last year against the City of Tulsa, as DeNeen L. Brown reports for the Washington Post. Previous attempts to secure reparations, including a lawsuit dismissed by the Supreme Court in 2005, have failed.

“I really believe that the work ordinary and committed people are doing in transcribing these materials related to the Tulsa Race Massacre and its reverberations to today is not purely personal or educational. It is in fact extraordinary,” Gardullo says. “Transcribers of these materials are accurately documenting and democratizing the truth and centering the stories of survivors, witnesses and their families. … [T]his should be seen as part of the practice of reparative or restorative justice work.”

In recent months, Transcription Center volunteers have demonstrated enormous enthusiasm for work related to Black history. This February, during Black History Month, citizen historians transcribed more than 2,000 pages of documents—many completed within the first 24 hours of being posted, according to Douglas Remley, a rights and reproduction specialist at NMAAHC.

Overall participation in the Transcription Center’s projects has soared during the last year, with many history enthusiasts stuck at home during the Covid-19 pandemic, says team member Courtney Bellizzi. In fiscal year 2019, 355 new volunteers participated in NMAAHC projects; in the 2020 fiscal year, by comparison, the museum gained 2,051 unique volunteers. Since October 2020, an additional 900 unique volunteers have contributed to the museum’s transcriptions.

The Smithsonian’s Transcription Center has been crowdsourcing transcription help from the public since 2013. Interested members of the public can join 50,480 “volunpeers” at transcription.si.edu and follow the center’s Twitter for updates on new projects as they launch.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)