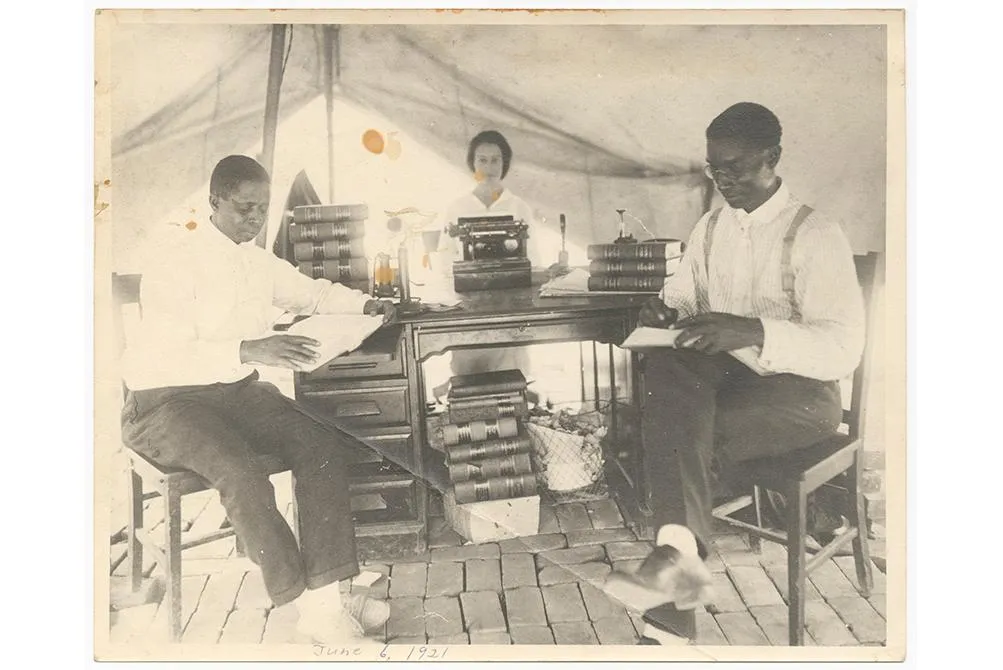

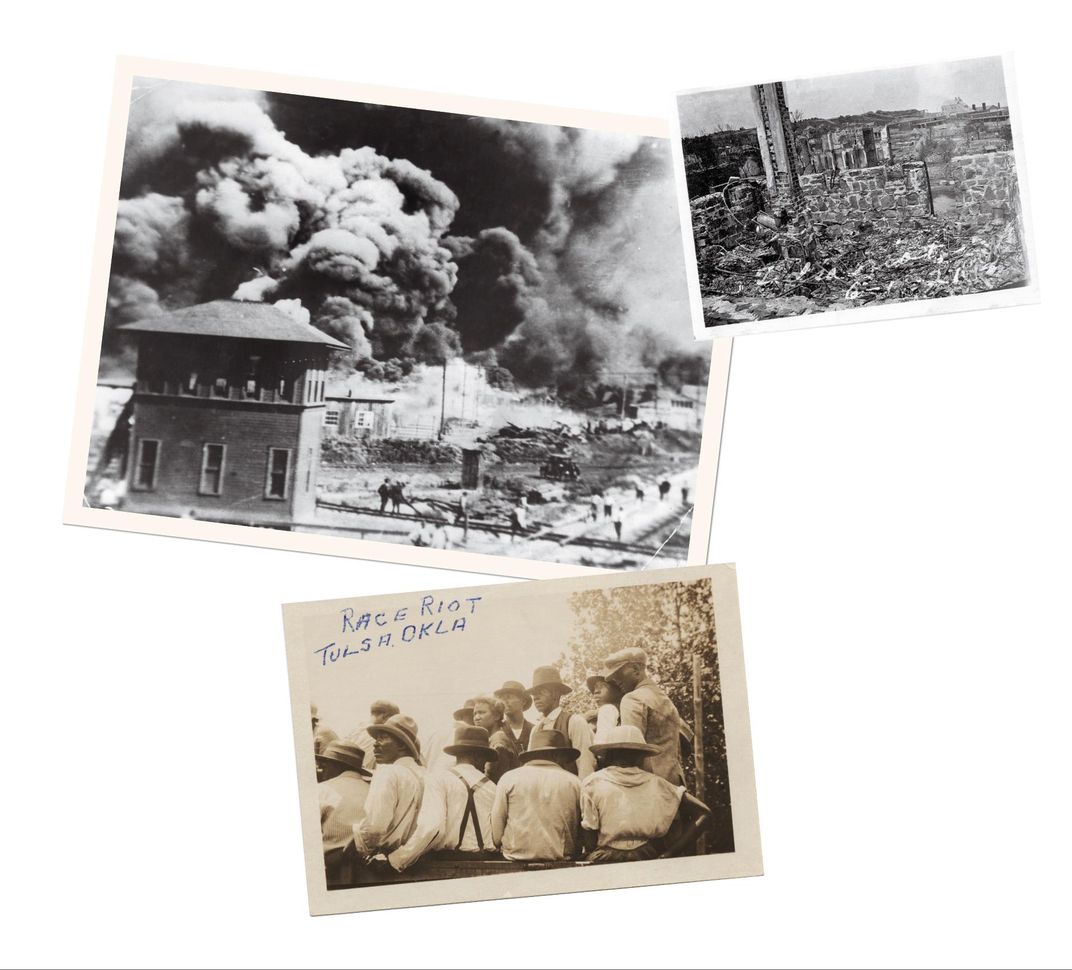

At 5:08 a.m. on June 1, 1921, a whistle pierced the predawn quiet of Tulsa, Oklahoma. There was disagreement later about whether the sound came from a steam engine on the railroad tracks or from a factory in the center of the booming oil town, but there was no doubting its meaning. It was the signal for as many as 10,000 armed white Tulsans, some dressed in Army uniforms from their service in World War I, to attack the place known as Greenwood, the city’s uniquely prosperous African American community. “From every place of shelter up and down the tracks came screaming, shouting men to join in the rush toward the Negro section,” a white witness named Choc Phillips later remembered. By dawn, “machine guns were sweeping the valley with their murderous fire,” recalled a Greenwood resident named Dimple Bush. “Old women and men and children were running and screaming everywhere.”

The trouble had begun the day before. A black teenage shoeshine boy named Dick Rowland had been arrested and charged with assaulting a white girl in an elevator of a downtown Tulsa building. Even white police detectives thought the accusation dubious. The consensus later was that whatever happened between them was innocuous, perhaps that Rowland had stepped on the toe of young Sarah Page when the elevator lurched. But that was academic after the Tulsa Tribune, one of the city’s two white newspapers, ran an incendiary editorial under a headline residents remembered as “To Lynch Negro Tonight.”

That evening, black community leaders met in the Greenwood newspaper office of A.J. Smitherman to discuss a response. Already a white mob had gathered outside the courthouse where Rowland was being held. Some African American leaders counseled patience, citing the promise of Sheriff Willard McCullough to protect Rowland. Others wouldn’t hear of it. A cadre of about 25 black residents, some in their own Army uniforms and carrying rifles, shotguns, pistols, axes, garden hoes and rakes, drove south from Greenwood and marched the final blocks to the courthouse and offered the sheriff their assistance.

At about 10:30 p.m., when a second group of 75 or so residents marched to the courthouse, an elderly white man tried to grab the gun of a black World War I veteran. A shot went off during the scuffle. Scores of other shots were fired in the panic that followed. Men, women and children dove for cover behind trees and parked cars, but as many as a dozen people of both races ended up dead.

The black marchers retreated to Greenwood. A lull set in after 2 a.m., but tensions rose in the hours of darkness. Then the whistle rang out. Armed black residents hiding on the rooftops of the sturdy brown-brick buildings lining Greenwood Avenue attempted to repel the white mob. But the mob not only had superior numbers; it also had machine guns, which were placed at elevated points on the edge of Greenwood, as well as biplanes, perhaps belonging to a local oil company, which circled overhead and rained bullets and dropped incendiaries.

(As part of our centennial coverage of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, read about how Oklahoma went from a beacon of racial progress to suppression and violence in “The Promise of Oklahoma”)

Members of the white mob, which included teenage boys and some women, went from business to business, church to church, home to home, hefting weapons, torches and containers of kerosene, rousting African American shop owners and residents and killing those who resisted and some who did not.

A white Tulsa resident named Walter Ferrell, who was a boy at the time of the massacre, recalled years later how he used to play every day with three black children who lived across the street from him on the border of Greenwood. On the morning of June 1, young Walter watched as a carload of white men entered the home of his friends. Then he heard a series of gunshots. He waited for his friends to flee from the flames engulfing their residence, but they never did. “It’s just too terrible to talk about, even decades later,” Ferrell told an interviewer in 1971.

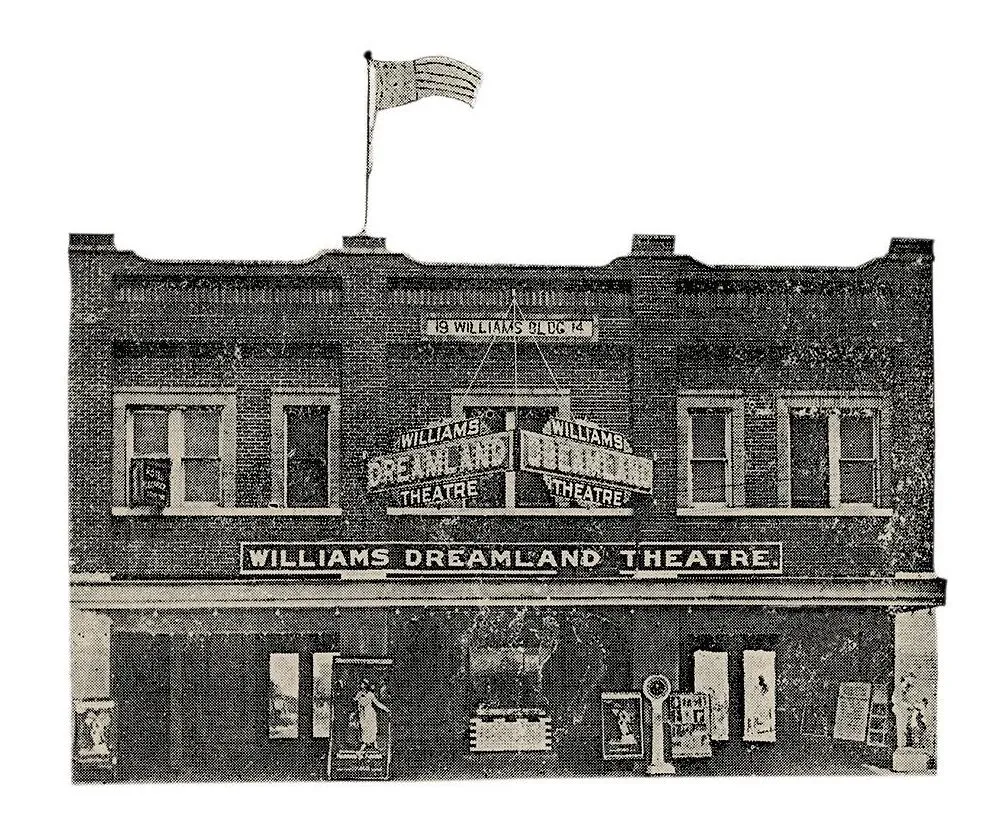

W.D. Williams was 16 years old at the time. His family owned the thriving Williams’ Confectionary at the corner of Greenwood Avenue and Archer Street. Just down the block was their Dreamland Theater.

When the attack came, W.D. Williams fought next to his father, John, who fired down at armed invaders from an upper floor of the Williams Building until the place that was both their home and place of business was overrun. When the teenager eventually surrendered, he was marched down Greenwood Avenue with his hands in the air, past his family’s flaming theater and candy store. He watched as a white looter emerged from his home with a fur coat belonging to his mother, Loula, stuffed inside a bag.

Eldoris McCondichie was 9 years old on the morning of June 1. She was roused early by her mother. “Eldoris, wake up!” she said. “We have to go! The white people are killing the colored folks!”

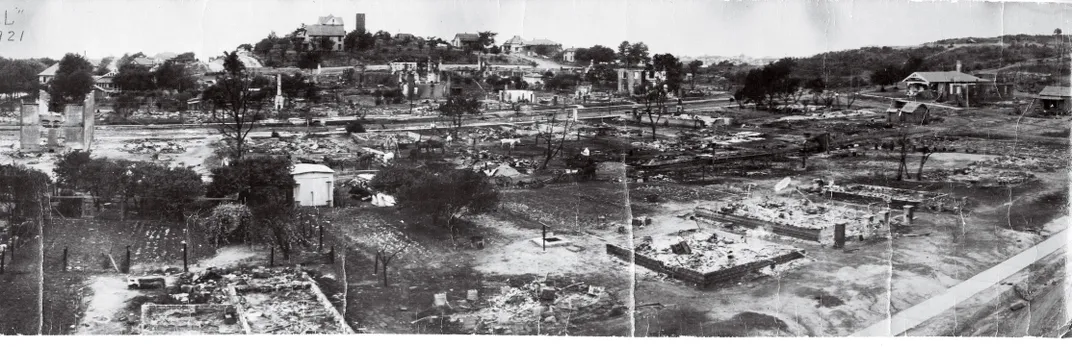

On a morning nearly 80 years later, as I sat in her Tulsa living room, McCondichie remembered how she and her parents joined a long line of black people headed north along the railroad tracks, away from the advancing mob. Many were dressed only in nightclothes, clutching pets and family Bibles. She recalled that a plane appeared, buzzing low and spraying bullets, causing her to pull away from her father and flee into a chicken coop. Her father pulled her out and back into the line of refugees. McCondichie and her family returned to Greenwood a few days later and found their home among the few still standing, but almost everything else within eyesight had been reduced to piles of charred wood and rubble. “By now, I know better than to talk about that day without holding a few of these,” she said, rising to take a handful of tissues.

After the fires burned out, Greenwood, known at the time as the Negro Wall Street of America, on account of its affluence, resembled a city flattened by a massive bomb. The mob had burned more than 1,100 homes (215 more were looted but not burned), five hotels, 31 restaurants, four drugstores, eight doctors’ offices, a new school, two dozen grocery stores, Greenwood’s hospital, its public library and a dozen churches. In all, 35 square blocks were destroyed. Most of the area’s 10,000 residents were left homeless. Estimates of losses in property and personal assets, by today’s standards, range from $20 million to more than $200 million.

A white Tulsa girl named Ruth Sigler Avery recalled a grim scene: “cattle trucks heavily laden with bloody, dead, black bodies,” Avery wrote decades later in an unfinished memoir. “Some were naked, some dressed only in pants....They looked like they had been thrown upon the truck beds haphazardly for arms and legs were sticking out through the slats....On the second truck, lying spread-eagled atop the high pile of corpses, I saw the body of a little black boy, barefooted, just about my age....Suddenly, the truck hit a manhole in the street. His head rolled over, facing me, staring as though he had been frightened to death.”

There is no complete tally of how many were killed. The best estimates put the number at as many as 300 people, the vast majority of them black. The exact number of casualties—and the location of their remains—may never be known. Many Greenwood families simply never saw or heard from their loved ones again, and were condemned to live with uncertainty about their fate.

That was the first act of Tulsa’s willful forgetting: to bury the truth of what had happened.

I first learned about the massacre 21 years ago, as a reporter at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, from a wire-service story about the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. The commission was created in 1997 by the State Legislature to document an event that few people knew much about, apart from elderly survivors and those they had entrusted with their memories.

I was incredulous. How could I not have known about something so horrible? I went to Tulsa to report on the massacre, and on that first trip and many that followed, I met with survivors such as Eldoris McCondichie and Kinney Booker and George Monroe, who were children during the massacre. I heard descendants compare Greenwood households to those of Holocaust survivors; black children and grandchildren sensed a darkness but could only guess at the source of it. I spoke with a white historian named Scott Ellsworth, who had made uncovering the truth about what happened his life’s work. And I sat down with Tulsa’s Don Ross, a black Oklahoma state representative and a civil rights activist who had introduced the resolution to create the government commission along with a state senator named Maxine Horner.

On my first night in Tulsa, Ross and I had taken a table at a Chinese restaurant and were looking at menus when I asked what I thought was an innocent question: “What was it like for African Americans after the Civil War?”

Ross brought his fist down on our table, loud enough to draw glances from people seated nearby. “How can you not know these things?” he asked, his voice rising. “And you’re one of the educated whites. If we can’t count on you to understand, who can we count on?”

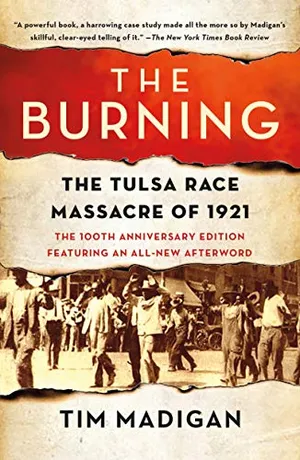

I spent much of the next year immersing myself in the story of the massacre and our country’s racial history, and went on to write a book about it, The Burning, published in 2001. I had been further astounded to learn that what happened in Tulsa was unique only in its scope. In the years leading to 1921, white mobs murdered African Americans on dozens of occasions, in Chicago, Atlanta, Duluth, Charleston and elsewhere.

I also learned that at first Tulsa’s white leaders were contrite. “Tulsa can only redeem herself from the country-wide shame and humiliation into which she is today plunged by complete restitution and rehabilitation of the destroyed black belt,” former mayor Loyal J. Martin said days after the massacre. “The rest of the United States must know that the real citizenship of Tulsa weeps at this unspeakable crime.” But, by July, the city had proposed building a new railroad station and white-owned manufacturing plants where Greenwood homes and businesses had stood. The Tulsa City Commission passed a new fire ordinance mandating that residential buildings be constructed with fireproof materials—an ostensible safety measure that had the effect of making it too expensive for many black families to rebuild. It was only when black lawyers rushed to block the ordinance in court that Greenwood could begin to come back to life.

Then, in a matter of months, once reporters for national newspapers disappeared, the massacre disappeared with it, vanishing almost completely for more than half a century. The history has remained hard to find, as if the events are too horrible to look at, and the depredations too great to comprehend.

I returned to the subject in recent months, as the 100-year anniversary drew near. I found that even at this time of social unrest much has changed since I learned about the massacre 21 years ago. Events have forced this forgotten history into the nation’s consciousness, and there is a new willingness to confront it.

Phil Armstrong is the project director for the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, an organization working with the city and other partners to plan a ten-day commemoration scheduled to begin May 26. Armstrong’s office is near the intersection of Greenwood Avenue and Archer Street, long known as Deep Greenwood. Construction workers there are now putting the finishing touches on Greenwood Rising, a gleaming new history center that will be dedicated on June 2. A quotation will adorn one exterior wall, words chosen in a poll of the community. “We had about five different quotes—from Martin Luther King Jr., from Desmond Tutu, from the black historian John Hope Franklin,” Armstrong told me. “But this quote from James Baldwin far and away had the most votes: ‘Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.’”

* * *

The conspiracy of silence that prevailed for so long was practiced on a vast scale. But one day in the late 1950s, at Tulsa’s Booker T. Washington High School, during a meeting of the yearbook staff, W.D. Williams, a history teacher, could hold his tongue no longer. “When I was a junior at Washington High, the prom never happened, because there was a riot, and the whites came over the tracks and wiped out Greenwood,” Williams told a roomful of students. “In fact, this building was one of the few that wasn’t burned, so they turned it into a hospital for colored folks. In those days, there were probably Negroes moaning and bleeding and dying in this very room. The whites over yonder burned Greenwood down, and with almost no help from anybody, the Negroes built it back to what it was.”

In the back of the room, a young pool hustler named Don Ross jumped up from his seat. “Mr. Williams, I don’t believe that,” Ross remembered saying. “I don’t think you could burn this town down and have nobody know nothing about it.”

The next day, the teacher showed the teenager a scrapbook filled with photographs of charred corpses and burned-out buildings. Williams soon introduced Ross to others who had lived through the massacre. As they drove one night to meet another survivor, Ross summoned the nerve to ask Williams how such a thing could have remained a secret. “Because the killers are still in charge in this town, boy,” Williams answered. “Now you understand why anyone who lived through this once damn sure doesn’t want to live through it all again. If you ask a Negro about the riot, he’ll tell you what happened if he knows who you are. But everyone’s real careful about what they say. I hear the same is true for white folks, though I suspect their reasons are different. They’re not afraid—just embarrassed. Or if they are afraid, it’s not of dying. It’s of going to jail.”

The historian Scott Ellsworth showed up at W.D. Williams’ home in North Tulsa, the historically black part of the city that includes the Greenwood district, in August of 1975. Ellsworth had heard whispers about the massacre while growing up in Tulsa in the 1960s, and he still didn’t understand how an incident on a Tulsa elevator could lead to the destruction of an entire community. It was Ruth Sigler Avery who suggested talking with Williams. “He had been looking all his life to tell his story, waiting for a professor from Howard University or Ohio State or a reporter from Ebony, and nobody ever came,” Ellsworth told me last year. “He sure wasn’t waiting for me.” At Williams’ kitchen table, Ellsworth laid out a painstakingly drawn map of Greenwood as it existed in 1921. “He is now wide-eyed, in a trance, because this is a map of his childhood,” Ellsworth recalled. “Then he looks up and says, ‘Tell me what you want to know.’ I had made the cut with him. That was the moment when we saved the history of the riot.”

At the time, the event in Tulsa was known, to the extent it was known at all, as a “race riot”—always a gross misnomer. “Facts mattered to W.D. Williams,” Ellsworth told me. “I don’t recall any particular emotionality or outward catharsis on his part. Sitting there at his kitchen table, he was completely changing the narrative that had held sway for more than a half century. And he wanted to make sure that I got it right.”

That interview was the first of dozens Ellsworth conducted with massacre survivors and witnesses, conversations that became the heart of his groundbreaking book, Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, published by LSU Press in 1982. “It had an underground existence,” Ellsworth said of his book. “Every year it was one of the most stolen books from the Tulsa library system. Every year I would send them a new box.” (Ellsworth’s long-awaited follow-up, The Ground Breaking, will be published this May.)

In 1995, thanks to Death in a Promised Land, an awareness of the massacre went more mainstream, after an Army veteran named Timothy McVeigh detonated a bomb outside a federal building in downtown Oklahoma City. The attack killed 168 people, including 19 children attending a day care center in the building. Nearly 600 other people were injured. The national news media descended on the city to cover what was described as the worst act of domestic terrorism in American history.

Don Ross, by then a state legislator who for years had represented the district that included Greenwood, believed that America’s worst domestic atrocity had happened 74 years earlier, in Tulsa. A few days after the Oklahoma City bombing, Ross met with Bryant Gumbel, host of NBC’s “Today” show, and handed him a copy of Death in a Promised Land. “Today” went on to produce a segment about the massacre for its 75th anniversary the following year. Amid the publicity that followed, Ross co-sponsored the resolution in the Oklahoma Legislature that led to the Tulsa Race Riot Commission.

The 11-member commission had two main advisers: John Hope Franklin, a revered African American historian and a Tulsa native, and Scott Ellsworth. When, two years later, the commission announced that it would begin investigating possible sites of mass graves, the public response was enormous, as if the pent-up pain of keeping such secrets had finally exploded into the daylight. Hundreds of people contacted commission investigators, many of them wanting to share personal memories of the massacre and how it had affected their families over the years. The commission discovered reams of government and legal documents that had been hidden away for decades. “Each opened an avenue into another corner of history,” Danney Goble, a historian, wrote in the commission’s final report.

The commission concluded there was no doubt white Tulsa officials were to blame for the massacre; they not only failed to prevent the bloodshed but had also deputized white civilians who took part in the burning and killing. And yet not one white person was brought to justice for the atrocities. The commission’s 200-page report was submitted to state and city officials on February 28, 2001. The “silence is shattered, utterly and permanently shattered,” Goble wrote. “Whatever else this commission has achieved or will achieve, it already has made that possible.”

Even so, there remains an unmistakable sense among Tulsa’s black community that important steps were left untaken. The commission recommended financial reparations for survivors and their descendants, a suggestion that state and local officials rejected. As Tulsa prepares to commemorate the 100-year anniversary of the massacre, the question of restitution remains unanswered.

* * *

One gray afternoon last fall, I stood at the intersection of Greenwood and Archer. It was a cold day, with low clouds and the occasional spit of rain. A red construction crane towered over the intersection, where work had begun on Greenwood Rising. There was the three-story Williams Building, circa 1922, rebuilt to resemble the original. Next door was a “Black Wall Street” T-shirt and souvenir store. Farther down Greenwood Avenue was a hamburger place, a beauty salon and a real estate office. Two blocks north, I walked beneath the ugly concrete gash of a freeway overpass that has divided Tulsa’s African American community for decades. Close by was a baseball stadium, home of the Drillers, Tulsa’s minor-league team, and sprawling apartment complexes under construction. The neighborhood’s gentrification is a source of resentment among many longtime black residents.

Small bronze plaques were set into the sidewalks up and down Greenwood Avenue and Archer Street. I might have missed them entirely if passersby hadn’t pointed them out. Don Ross had been involved in putting the first one down 30 years ago; each commemorates the location of a business before June 1, 1921. The Dreamland Theater. Nails Brothers’ Shoe Shop. Dr. Richard Walker. Abbott Printing. Colored Insurance Association. Hooker Photography. C.L. Netherland, Barber. Hughes Café. Gurley Hotel. The Williams Building. Attorney I.H. Spears.

The little monuments, one after another down the street, had a stark but beautiful power. Each one noted whether or not the business had ever been revived. By my count, in just these few blocks, 49 had reopened after the massacre. Twenty-nine had not.

The Heart of Black Tulsa

Editor's Note, May 11, 2021: A previous version of this map misspelled the name of T.J. Elliott. We regret the error.

Among the latter was the office of A.C. Jackson, a nationally respected physician who was shot dead outside his home as he attempted to surrender to the mob. A couple of blocks away was a marker for the Stradford Hotel, at the time the largest black-owned hotel in the United States, the culmination of a remarkable American journey that had begun in slavery. The Stradford Hotel was never rebuilt, either.

* * *

Late in his life, J.B. Stradford set down his memoirs in careful cursive, later transcribed into 32 typewritten pages. The manuscript has been handed down to six generations and counting. For those who share Stradford’s blood, it is a sacred text. “It’s like the family Magna Carta or Holy Grail or Ten Commandments,” Nate Calloway, a Los Angeles filmmaker and Stradford’s great-great-grandson, told me recently.

Calloway first read the memoirs nearly three decades ago, when he was in college, and has gone back to them many times in his effort to bring Stradford’s story to the screen. Though the memoir is closely held by the family, Calloway agreed last fall to study it again on my behalf and share some of its contents.

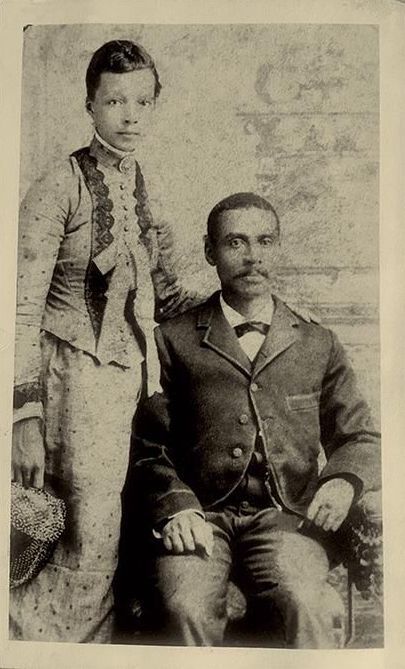

The story begins on September 10, 1861, in Versailles, Kentucky, the day John the Baptist Stradford was born. He was the son of a slave named Julius Caesar Stradford and the property of enslaver Henry Moss. The enslaver’s daughter changed the Stradford family’s trajectory by teaching J.C. to read and write. J.C. taught his children.

In 1881, not even two decades after the end of the Civil War, J.B. Stradford enrolled at Oberlin College, in Ohio, where he met the woman he would marry, Bertie Wiley. After graduation, the couple returned to Kentucky, but now the young man was a school principal and the owner of a barbershop.

Stradford’s memoir describes the chilling story of a black man accused of raping a white woman. “She was having an affair with one of her servants, and the husband walked in and caught the two of them,” Calloway said, summarizing the passage. “She yelled ‘rape.’ The black guy ran away and the whites caught him. Stradford said others in his community ran and hid, because typically what would happen is that the whites would unleash their wrath on the entire black community. But Stradford didn’t run. He intentionally went to witness the lynching. He wrote that the man was hanged up by a tree, but his neck did not snap. He suffocated. The most vivid detail was how the black man’s tongue was hanging out of his mouth.” Calloway went on, “That had a big impact on him. Moving forward, when it came to lynching, he wasn’t going to stand for it, to sit by.”

Stradford took his family to Indiana, where he opened a bicycle store as well as another barbershop. In 1899, he earned a law degree from the Indianapolis College of Law, later absorbed by Indiana University. Then, early in the new century, Stradford heard about the black communities springing up in what would become the state of Oklahoma. After Bertie died unexpectedly, Stradford decided to stake his claim in a former Native American trading village on the Arkansas River called Tulsa that had begun to attract oil men and entrepreneurs.

Stradford arrived on March 9, 1905. Eight months later, oil drillers hit the first gusher a few miles from the village. The Glenn Pool Oil Field would be one of the nation’s most bountiful producers of petroleum for years to come.

Tulsa became a boomtown virtually overnight. White Tulsans flush with cash needed carpenters and bricklayers, maids and cooks, gardeners and shoeshine boys. African Americans came south over the railroad tracks to fill those jobs, then took their pay home to Greenwood. An African American professional and entrepreneurial class sprang up, and no black Tulsan prospered more than J.B. Stradford. In little more than a decade, his holdings came to include 15 rental houses and a 16-room apartment building. On June 1, 1918, the Stradford Hotel opened at 301 Greenwood Avenue—three stories of brown brick, 54 guest rooms, plus offices and a drugstore, pool hall, barbershop, banquet hall and restaurant. The hotel was said to be worth $75,000, about $1 million in today’s dollars.

But for all his success and personal happiness—in Tulsa he found love again and married a woman named Augusta—there was some question about whether Stradford would live long enough to enjoy it. He and A.J. Smitherman, the editor of Greenwood’s Tulsa Star, gathered groups of men to face down lynch mobs in surrounding towns. In those days, black people were killed for much less. “It was remarkable he was able to live out his natural life,” Calloway told me. “But, then again, he almost didn’t.”

On the night of May 31, 1921, as the confrontation between the city’s black and white communities drew near, Stradford, rather than march to the courthouse, stayed in Greenwood to be available to provide legal representation to any black residents who might be arrested. His memoir continues:

The mob organized with the agreement that at the sound of whistles from the large factories at five o’clock they were to attack the “Black Belt.” The Boy Scouts accompanied them. They were furnished with a can of kerosene oil and matches....Houses were pillaged and furniture taken away in vans. Then, the fire squad came along to light the fires.

They kept up their plundering, burning and killing until they came within two blocks of my hotel....I can’t say whose plane it was....It came sailing like a huge bird, in the direction of the hotel; about two hundred feet above the ground and just before it reached the hotel it swerved and shot bombs through the transoms and plate glass windows.

A dozen people, at least, were in the lobby. One man was shot running out and many others were wounded. All were frightened to hysteria....The men pledged to die with me, if need be, defending the hotel, but the plane episode destroyed their morale. The women, crying and pleading, said, “Let’s get out. Maybe we can save our lives.” They turned in their guns and ammunition, leaving me alone with my wife, who knew me too well. She said, “Papa, I’ll die with you.”

The mob caught one of the patrons and inquired about the number of people in the hotel and if J.B. had an arsenal. The captured patron was sent back with the message that they were officers of the law and came to take me to a place of safety. They guaranteed that my hotel would not be burned, but used for a place of refuge. I opened the door to admit them, and just at that instant, a man was running across a lot southeast of the hotel trying to make his getaway. One of the rioters fell to his knees and placed his revolver against the pillar of the building and shot at him. “You brute,” I yelled. “Don’t shoot that man.”

Just as I was getting in an automobile, the raiding squad arrived on the scene and broke open the drug store and appropriated cigars, tobacco and all the money in the cash register. The perfume they sprinkled over themselves. They filled their shirts with handkerchiefs, fine socks and silk shirts.

I saw lines of people marching with their hands above their heads and being jabbed by the guards with guns if they put their hands down. The guards acted like madmen....Oh! If only you could have seen them jumping up and down uttering words too obscene to be printed, striking and beating their prisoners.

We went out Easton Avenue. On the northwest corner of Elgin and Easton Avenues I owned eight tenement houses. As we passed, flames were leaping mountain high from my houses. In my soul, I cried for vengeance and prayed for the day to come when the wrongs that had been perpetrated against me and my people were punished.

Stradford was interned with his wife and son along with hundreds of others at Tulsa’s Convention Hall. In all, thousands of displaced Greenwood residents were herded into places such as the hall, ballpark and fairgrounds. At the convention hall, Stradford’s son overheard white officials scheming to abduct Stradford. “We will get Stradford tonight,” one of them said. “He’s been here too long...and taught the n------- they were as good as white people. We will give him a necktie party tonight.”

A white friend of the family’s agreed to help them escape. He backed his car to a side door of the convention hall and the Stradfords slipped out. J.B. Stradford crouched down in the backseat, his head in his wife’s lap as the car sped away. By the next day, the couple had made it to Independence, Kansas, where Stradford’s brother and another son were living.

In the aftermath of the massacre, at least 57 African Americans were indicted in connection with it, including Dick Rowland for attempted rape. (None were ever tried or convicted. Tulsa authorities, apparently, had little stomach for revisiting the massacre in court.) Stradford was one of the first to be charged—accused of inciting a riot.

The Tulsa police chief himself showed up at the door of Stradford’s brother in Kansas. The chief did not have an arrest warrant, and J.B. Stradford threatened to shoot the officer if he tried to enter the house. The chief retreated. Sheriff Willard McCullough later got Stradford on the telephone and asked if he would waive extradition, voluntarily turn himself in and face charges in Tulsa.

“Hell, no,” Stradford said, and hung up.

Stradford’s 29-year-old son, C.F. Stradford, had recently graduated from Columbia Law School, and was then in the early stages of what would be a long and distinguished legal career in Chicago. The son, packing a pistol, arrived in Independence and got his father on a train north. By then, J.B. Stradford knew his hotel had been destroyed by fire, his hard work and dreams vaporized.

Tulsa authorities did not pursue Stradford to Chicago. He never returned to the city where he had achieved his greatest successes, nor did he receive any financial compensation for all he had lost. Stradford wasn’t able to recreate a luxury hotel in Chicago, but in his later years he owned a candy store, a barbershop and a pool hall. Descendants say he remained embittered about the Tulsa massacre until his death in 1935, at the age of 74.

His descendants went on to become judges, doctors and lawyers, musicians and artists, entrepreneurs and activists. His granddaughter Jewel Stradford Lafontant, for example, was the first black woman to graduate from the University of Chicago Law School, in 1946, and later became the first woman and first African American to serve as a deputy solicitor general of the United States. Richard Nixon considered nominating her to the U.S. Supreme Court. Her son, John W. Rogers Jr., is an investor, philanthropist and social activist who formed what is the nation’s oldest minority-owned investment company, Chicago-based Ariel Investments.

“I feel for J.B. Stradford, overcoming all these obstacles to build a great business and see that business thriving and then overnight to see it destroyed through pure racism,” Rogers told me last year. “I can’t imagine how devastating that would be. It’s just unimaginable heartache and bitterness that comes from that.”

Stradford’s descendants also never forgot that he had technically died a fugitive, and they were determined to set that right. The fight was led by his great-grandson, a Chicago judge named Cornelius E. Toole, and by Jewel Lafontant. State Representative Don Ross also joined the effort, which resulted in a historic ceremony at the Greenwood Cultural Center in 1996, 75 years after the massacre. About 20 members of Stradford’s family gathered from around the nation to hear Oklahoma Gov. Frank Keating read an official pardon. “It was truly a homecoming of sorts,” Erin Toole Williams, Stradford’s great-great-granddaughter, told me. “None of us had ever been to Tulsa, but the welcome was so warm from the members of the Greenwood community, from other descendants of victims.” After the ceremony, officials hosted a reception. “They had enlarged photographs of lynchings and pictures of the ruins of my great-great-grandfather’s hotel,” Toole Williams said. “That just took me down. I just sobbed along with my family. It was all coming full circle, making for a very bittersweet moment.”

Nate Calloway, who was born and raised in Los Angeles, made his first trip to Tulsa in 2019. On a crisp autumn afternoon, he finally stood before the commemorative plaque in the sidewalk at 301 Greenwood Avenue. The place where the Stradford Hotel once stood was a grassy lot between a church and the freeway overpass. “It was very emotional,” Calloway told me. “But you know, when I went there and I saw those plaques, I got very upset. They took away all that property from those people, property that would be worth tens of millions of dollars in today’s wealth, and they replaced it with plaques.”

Recently, Calloway searched through Tulsa property records to find out what happened to Stradford’s land after the massacre. He learned that in November 1921 Stradford sold his burned-out real estate to a white Tulsa property broker for the price of a dollar. According to later court records, the broker had agreed to sell the property and give Stradford the proceeds, but he never had. “It appears he was defrauded,” Calloway told me. “It adds insult to injury.”

* * *

Teaching the history of the massacre has been mandatory in Oklahoma’s public schools since 2002, a requirement that grew out of the work of the state commission. Last year, state officials announced that the Oklahoma Department of Education had taken it a step further, developing an in-depth curricular framework to facilitate new approaches to teaching students about the massacre. Amanda Soliván, an official for Tulsa Public Schools, cited the example of an “inquiry driven” approach that has teachers pose questions about the massacre in the classroom—for example, “Has the city of Tulsa made amends for the massacre?”—and challenges students to study primary sources and arrive at their own conclusions. “I don’t need to be lecturing students whose ancestors might have experienced the Tulsa Race Massacre,” Soliván told me. U.S. Senator James Lankford, a Republican, had been one of the new curriculum’s most vocal advocates. “A lot of things need to be done by that 100-year mark,” he said at a press conference announcing the changes. “Because quite frankly, the nation’s going to pause for a moment, and it’s going to ask, ‘What’s happened since then?’”

The new educational approach is one of several initiatives the state, the city, and their private partners are pursuing as part of a broad effort to reckon with the legacy of the massacre and, officials and community members hope, create the conditions for lasting reconciliation. The city of Tulsa is sponsoring economic development projects in North Tulsa, which includes historic Greenwood. The Greenwood Art Project selects artists whose works will be featured as part of the centennial commemoration. But, for many, the most significant major initiative has been the renewal of the search for the graves of murdered massacre victims.

Much of the civic soul-searching is being led by Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum, a Republican born and raised in the city. Last year, Bynum told me that he himself hadn’t heard anything about the massacre until a night 20 years ago, at a political forum at a library in North Tulsa. “Someone brought up that there had been a race riot, and that bombs had been dropped on residents from airplanes,” Bynum told me. “I thought that was crazy. There was no way that would have happened in Tulsa and I would not have heard about that before.”

Bynum had reason to be astonished. There was little that happened in Tulsa that his family didn’t know about, going back to 1899, when Bynum’s paternal great-great-grandfather was elected the town’s second mayor. (His maternal grandfather and an uncle have also served as mayors.) “One of the ways I confirmed that it happened was that I went and asked both of my grandfathers about it,” Bynum said. “They both had stories to tell. They weren’t alive when it happened, but their parents had told them about it, so it became clear that it was something talked about within families but never publicly.”

I asked the mayor why he thought nobody spoke about it except privately. “The civic leadership in Tulsa realized what a disgrace this was for the city, and they recognized, frankly, what a challenge it would be for our city moving forward,” he said. “Then you had succeeding generations grow up, and it wasn’t taught in schools, it wasn’t written about in newspapers.”

Even after the state commission brought national attention to the massacre, it didn’t take long for media attention to move on, especially outside of Oklahoma. Then, in the fall of 2019, HBO premiered “Watchmen,” set largely in Tulsa, which used an alternate-history conceit to explore the city’s fraught racial dynamics. The show went on to win 11 Emmys. Nicole Kassell, who directed the pilot episode, which opens with an extended sequence depicting the massacre in haunting realism, told me, “I remember hearing after the pilot aired that there had been at least 500,000 internet hits that night of people researching the massacre of Tulsa, to find out if it was real. I palpably felt that even if the show failed from that moment forward, we had done our job.”

Mayor Bynum, in our conversation, described his own reaction to “Watchmen.” “To see it portrayed in such a realistic way—it filled me with dread,” he said. “But I also am incredibly grateful. There are so many tragedies related to that event, but one of them is that the people who tried to cover this up were successful for so long. To have a show like that raise awareness of it around the world is a great accomplishment. It’s one way we can make sure that the bad guys didn’t win. We can’t bring folks back to life, but we can make sure that those who tried to cover it up were not successful.”

Bynum had announced the year before the show aired that the city would finally reopen the search for the remains of massacre victims. “What I kept coming back to was this thought: ‘That’s what you hear happens in authoritarian regimes in foreign countries,’” he said. “They erase a historical event. They have mass graves.”

The mayor asked Scott Ellsworth to join a team that also included Oklahoma state archaeologist Kary Stackelbeck and Phoebe Stubblefield, a forensic anthropologist whose great-aunt lost her home in the massacre. The professionals would also work with citizen monitors that included J. Kavin Ross, a local journalist and the son of former state representative Don Ross, and Brenda Alford, a lifelong Tulsa resident and prominent local descendant of survivors.

Alford was already an adult when she learned that her grandparents and great-grandmother had fled from the mob. When they returned to Greenwood, their homes and family businesses—a store that sold shoes and records, a taxi and limousine service, a skating rink and a dance hall—had all been destroyed. When Alford learned about the massacre, cryptic childhood memories began to make sense. “When we would pass by Oaklawn Cemetery, especially when my great-uncles came to town, the comment would always be made, ‘You know, they’re still over there,’” Alford recalled. Of the hundreds of people interviewed by the original state commission, many told stories about rumored mass grave sites handed down across generations. One location that came up over and over again was Oaklawn, the city’s public cemetery.

In July 2020, she and Kavin Ross joined the search team at Oaklawn for the first excavation. It turned up animal bones and household artifacts but no human remains. The search resumed three months later, in late October. The team had historical evidence, including death certificates from 1921, suggesting that massacre victims may have been buried in unmarked graves at another site at Oaklawn. Geophysical surveys had revealed soil anomalies that were consistent with graves. On October 20, an early swipe of a backhoe uncovered human bones. A tarp was quickly thrown up to shield the remains.

“We went into motion very quickly,” Kary Stackelbeck, the state archaeologist, told me later. “But then it occurred to me that the monitors may not have been aware of what was happening. I took Brenda Alford to the side to quietly let her know that we had this discovery. It was that moment of just letting her know that we had remains. It was a very somber moment. We were both tearing up.”

In the coming days, at least 11 more unmarked graves were uncovered, all of them presumably containing the remains of massacre victims. Scott Ellsworth met me for dinner in Tulsa not long afterward. He told me about other possible grave sites yet to be explored and the fieldwork yet to be done. The process of analyzing the remains, possibly linking them to living relatives through DNA, arranging for proper burials, and searching for other sites is likely to go on for years. But in his nearly five decades of devotion to restoring the massacre to history, those autumn days last year at the cemetery were among the most seismic. They were also bittersweet. “I’m thinking of W.D. Williams and George Monroe, all those people I met in the ’70s,” Ellsworth told me. “I wish they could have been here to see this.”

* * *

Eldoris McCondichie, who had hidden inside a chicken coop on the morning of June 1, 1921, died in Tulsa on September 10, 2010, two days after she turned 99 years old. I have thought of her often in the years since we sat together in her Tulsa living room, discussing the horrible events of her young life.

On a sunny day last October, I waited for her granddaughter, L. Joi McCondichie, whom I had never met, at an outdoor café table on Greenwood Avenue, just across from the construction site of the Greenwood Rising history center. She showed up carrying files that documented her own attempts to organize a commemorative walk on June 1 for the 100-year anniversary of the massacre and newspaper stories that celebrated Eldoris’ life. She is a thin woman in her 50s, weakened from a spell of poor health. But where Eldoris was the picture of tranquillity, Joi could be fierce, pounding several times on her seat to emphasize a point during our long interview. In her family, Joi told me, “I was known as little Angela Davis.”

Joi had been born and raised in Tulsa, but moved to Los Angeles as a young woman to work for the federal government. She moved back to Tulsa several years ago with her son to be closer to family. Eldoris was the beloved matriarch. As a young girl, Joi remembered hearing her grandmother talk, but only in passing, about the day she had been forced to hide in a chicken coop. Eldoris never said why or from whom. It wasn’t until one day in 1999, when Joi was living in Los Angeles, that she got a call at work from a receptionist. “She said, ‘Do you know an Eldoris McCondichie?’ So I go to the front desk, and there Grandma is on the front page of the Los Angeles Times.” Joi remembered the headline exactly: “A City’s Buried Shame.” Joi and her toddler son caught the first plane back to Oklahoma.

Eldoris McCondichie was 88 years old when Joi and other similarly agitated grandchildren gathered in the den of her North Tulsa home. That day Eldoris told them, for the first time, about the lines of bedraggled refugees, the planes firing down, the wall of smoke rising from Greenwood.

“She calmed us down, not just me, but the rest of my cousins,” Joi said of her grandmother. “We were frantic and couldn’t understand, but she talked to us so calmly. She was sweet as pie. I said, ‘Why didn’t you tell us all this time, Grandma?’ And she simply looked at me and said, ‘It’s because of you, and it’s because of him.’ She pointed to the fat baby I was holding. It made me so angry—so disheartened and quite sad,” Joi continued. “I said, ‘Grandma, you should be mad. Let’s tear it down. Let’s get Johnnie Cochran in here.’

“She said, ‘I didn’t want you to carry that anger and that hate in your heart.’”

I asked Joi if her grandmother and other survivors felt relief at finally feeling safe enough to tell their stories. “Yeah, they were getting old,” she replied. “It was time. They could safely say they had won the war. They had lost the battle, but they had won the war, you see. These are the things that she told us to calm us down. She said, You can’t fight every battle. You have to win the war.”

* * *

Last year, in a report that renewed calls for reparations to be paid to Tulsa’s massacre survivors and their descendants, Human Rights Watch painted a sobering picture of what remains a segregated city. A third of North Tulsa’s 85,000 residents live in poverty, the report found—two and a half times the rate in largely white South Tulsa. Black unemployment is close to two and a half times the white rate. There are also huge disparities between life expectancy and school quality.

“I’m cutting yards today so that my son can get out of Langston University,” Joi McCondichie told me. “They didn’t give us a penny, sir, and now they’re going to make millions a year,” she said, referring to the predicted influx of tourism with the opening of Greenwood Rising.

John W. Rogers Jr., the Chicago investor and great-grandson of J.B. Stradford, spoke about the economic disadvantages that persist in black communities. “What I’ve been interested in is economic justice and in helping to solve the wealth gap in our country,” Rogers said. “I think that’s because I came from this family and from business leaders who understood that it was important for us to be able to vote, and important for us to get education and fair housing, but it was also important for us to have equal economic opportunity.”

It is against that complex backdrop that Tulsa commemorates the worst outbreak of racial violence in U.S. history. What happened in 1921 continues to reverberate in every part of the country. It’s possible to see a direct line from the enduring horror of the Tulsa Race Massacre to the outrage over the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis last year.

When we spoke last fall, Phil Armstrong, the project director for the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, shared his hopes that Greenwood Rising could become an incubator of sorts for new racial understanding. “The final chamber in Greenwood Rising is called ‘The Journey to Reconciliation,’” Armstrong said. “It’s going to be an amphitheater-style seated room. You’ve seen all this history. Now let’s sit down and have a conversation. It literally will be a room where people can have difficult conversations around race. You can change policies and laws, but until you change someone’s heart and mind, you’re never going to move forward. That’s what Greenwood Rising is all about.”

Editor's Note, March 24, 2021: A previous version of this story said that J.B. Stradford earned a law degree from Indiana University. In fact, he earned a degree from the Indianapolis College of Law, which was later absorbed by Indiana University. The story has been updated to clarify that fact. Additionally, a previous version of this map misspelled the name of T.J. Elliott. We regret the error.

Burning

An account of America’s most horrific racial massacre, told in a compelling and unflinching narrative. The Burning is essential reading as America finally comes to terms with its racial past.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/27/d5/27d50490-2c42-4ef0-82b3-9465a77eae23/mobile_opener.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a3/d4/a3d4a889-30c6-4607-b326-48bbda459097/openertulsa_v2.jpg)