Medieval Britons’ Remains Record the ‘Skeletal Trauma’ Inflicted by Inequality

New study reveals the horrific injuries sustained by lower-class members of English society

:focal(1462x292:1463x293)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6d/89/6d891362-3d17-47e2-96db-b1ae9ce40cc9/1sh-2560x1440.jpg)

From accidents to war, abuse and backbreaking labor, daily life in medieval Britain exacted a heavy physical toll on the kingdom’s citizens. Now, a new study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology suggests that the poorest members of English society bore the brunt of the trauma.

Per a statement, social inequality was literally “recorded on the bones” of lower-class medieval workers. At the same time, says lead author Jenna Dittmar, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge, “[S]evere trauma was prevalent across the social spectrum.”

During the medieval era, Dittmar concludes, “Life was toughest at the bottom—but life was tough all over.”

As Nicola Davis reports for the Guardian, the researchers based their findings on an analysis of 314 individuals, all ages 12 and over, buried in three burial sites around Cambridge between roughly 1100 and the 1530s. The team studied the fractures, breaks and injuries recorded in the remains to create a barometer of “skeletal trauma,” or measure of the hardship endured by different groups in medieval society.

Before the foundation of its famed university in 1209, Cambridge was a provincial town of about 2,500 to 4,000 artisans, friars, merchants and farm laborers of varying social status, according to the statement. X-ray analysis of the bones revealed that 44 percent of working-class people buried in a parish burial ground had bone fractures, versus 32 percent of those buried in an Augustinian friary and 27 percent of those buried near the Hospital of St. John the Evangelist. Across all remains, 40 percent of male skeletons had bone fractures, compared with just 26 percent of female skeletons.

Established at the end of the 12th century, the Hospital of St. John the Evangelist housed retired, infirmed, destitute or chronically ill Cambridge residents, operating both as a charitable refuge for the sick and a site similar to a retirement home. The hospital was dissolved in 1511 and later became St. John’s College, one of 31 colleges at the university. Archaeologists excavated the burial site while conducting renovations between 2010 and 2012.

Many of the St. John’s residents bear skeletal evidence of tuberculosis, a disease that would have prevented them from working. As Dittmar tells the Guardian, she found it surprising that just 27 percent of St. John’s residents had fractures, as hospitals are typically a place for the infirm. The researchers concluded that residents were more protected from violent mishaps than their peers—although one man buried there appears to have fractured his knee in a fall.

Life proved most difficult for the medieval people buried in the parish of All Saints by the Castle, a church founded in the tenth century and in use until 1365, when it merged with a neighboring parish after populations decreased in the wake of the bubonic plague, per the statement.

One woman buried in All Saints bears the possible indications of domestic abuse, Dittmar tells the Guardian: Her skeleton shows evidence of a broken jaw that never healed, broken ribs and a broken foot. In modern times, broken jaws in women are typically interpreted as a sign of domestic violence, Dittmar notes.

“Those buried in All Saints were among the poorest in town, and clearly more exposed to incidental injury,” says Dittmar in the statement. “At the time, the graveyard was in the hinterland where urban met rural. Men may have worked in the fields with heavy ploughs pulled by horses or oxen, or lugged stone blocks and wooden beams in the town.”

Speaking with CNN’s Amy Woodyatt, Dittmar notes that many people buried in the parish grounds would have worked as stonemasons or blacksmiths. Alongside their domestic duties, women would have tended to livestock and helped with the harvest—both physically strenuous tasks.

“Outside town, many spent dawn to dusk doing bone-crushing work in the fields or tending livestock,” Dittmar adds.

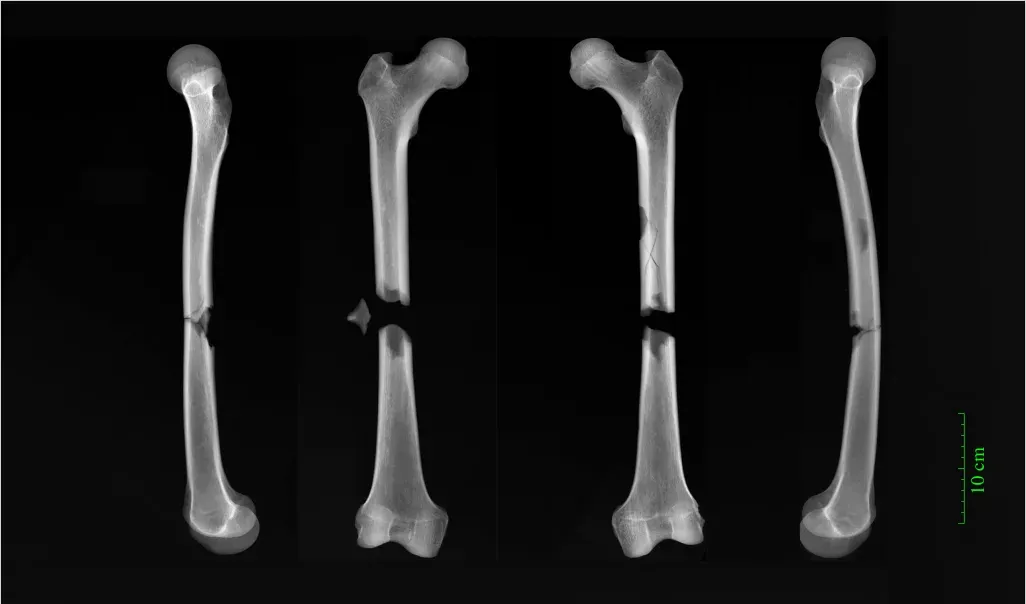

On the other end of the income spectrum, the Augustinian friary—excavated in 2016—was home to many wealthy donors, as well as members of the religious order. Though their wealth and status protected many of these people from serious bodily harm, even money wasn’t a guarantee of safety: One friar, identified by his belt buckle, was buried with two completely fractured femurs, or thigh bones.

The unlucky friar’s injuries bear a striking resemblance to the wounds sustained during car accidents today, says Dittmar in the statement.

“Our best guess [for the cause of his injuries] is a cart accident,” she concludes. “Perhaps a horse got spooked and he was struck by the wagon.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)