The Lost Art of Molding Ice Cream Into Eagles, Tugboats and Pineapples

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, ice cream makers used metal casts to create fanciful desserts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5d/6a/5d6a2060-9289-4cbb-a737-67c3d714e5d0/ice_cream_truck.jpg)

One of the toughest summertime decisions for any kid comes when the ice cream truck pulls up: SpongeBob SquarePants, Bugs Bunny or a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle?

That modern dilemma is evidence that we still like our ice cream treats shaped into recognizable figures. But current options at the ice cream truck pale in comparison to a mostly forgotten heyday of molded and shaped ice cream in America. During the latter half of the 19th century into the first half of the 20th, it was common for people to enjoy frozen summertime treats in all sorts of shapes: turkeys, flower bouquets, melons, even George Washington’s head.

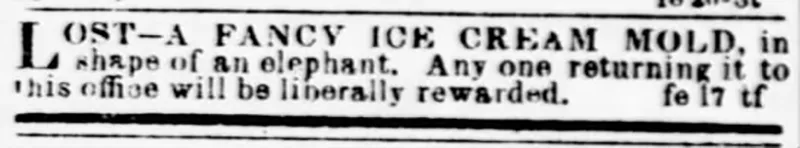

Ice cream makers treasured their molds. A bulletin in the February 22nd 1860 edition of Washington D.C.’s Evening Star reads, “LOST — A FANCY ICE CREAM MOLD, in shape of an elephant. Any one returning it to this office will be liberally rewarded.”

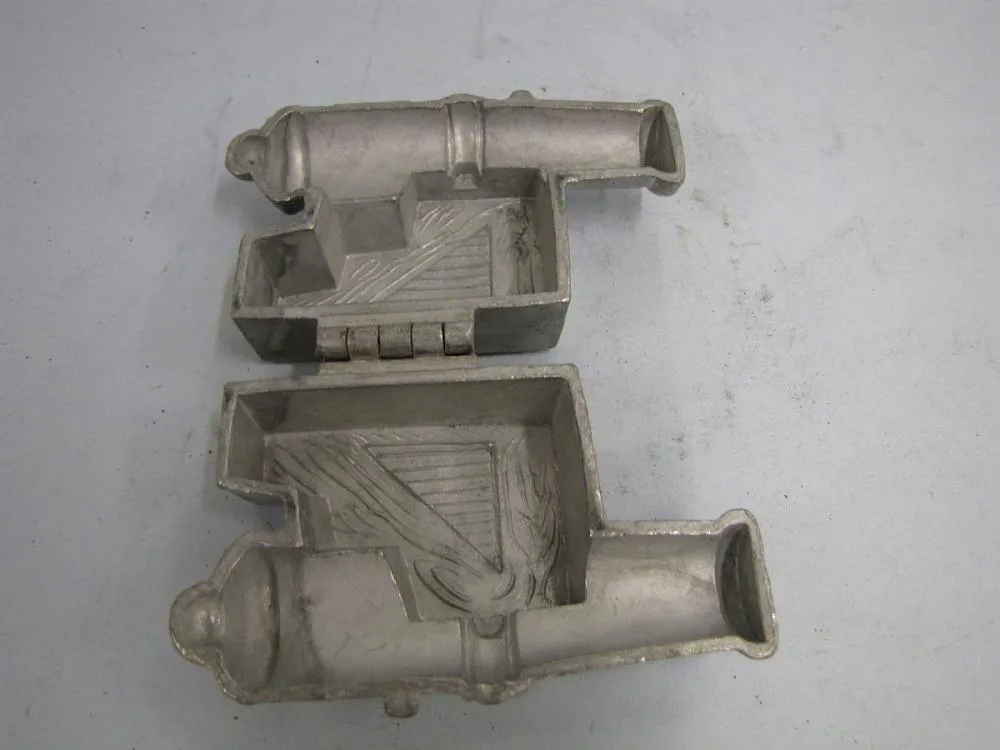

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History has one such mold in its collection. Manufactured by Eppelsheimer & Co. of New York, it’s not the missing specimen, but one produced half a century later. The elephant joins dozens of pewter molds in the museum’s trove from the 1920s and ’30s, including Uncle Sam, an eagle, a lion, a cannon and a witch on a broomstick.

“The enduring allure of ice cream was made even more delightful when molded into three-dimensional butterflies, dolphins, tugboats, political figures, and more,” says Paula Johnson, curator of food history at the museum. The collection, she says, “reflect[s] a broad enthusiasm for specialty treats.”

While it is impossible to pinpoint the first instance of ice cream being molded into a shape, recipe books describe ice creams made to look like fruits, vegetables, meats and cheeses in mid-18th century Europe. In addition to being molded into various shapes, the ice creams were flavored with ingredients to match the coloring of the objects they were meant to imitate (an ice cream made to look like an artichoke could be flavored with pistachio for its green hue, for example). If additional enhancements were needed, the creations were painted with food coloring.

Hannah Spiegelman, an ice cream historian and founder of the blog A Sweet History, traces the practice of molding frozen cream back to Medieval and Renaissance traditions of shaping sweets. “It all stems from the aristocracy[’s] desire for novelty and spectacle with a meal,” she says, “and having a visual hunger be satisfied as well.”

The results were so realistic that hosts would use them to play practical jokes on their dinner guests. “You would put out these ice creams in the shape of fruits or asparagus, as a kind of joke to the person you were serving,” says Jeri Quinzio, author of Of Sugar and Snow: A History of Ice Cream Making, “and there are stories about people being so surprised, you know, ‘I thought that was a peach, and it turned out to be ice cream.’”

The practice traveled across the Atlantic and is recorded in America as early as George Washington’s presidency. Washington was famously a lover of ice cream, and according to Mount Vernon, the household purchased two ice cream molds in May 1792 for $2.50 and another in June 1795 for $7. The shapes of these molds are unknown, but Anne Funderburg, author of Chocolate, Strawberry Vanilla: A History of American Ice Cream, posits they could have been large pyramids or towers, which were fashionable at the time.

It was in the mid-19th century when confectioners, caterers, restaurants, home cooks and even wholesale suppliers popularized the molds. At the time, ice cream was a centerpiece of social gathering. Ice cream gardens and parlors were popular, especially among women, as social norms didn’t permit them to frequent bars like their male counterparts. The growing Temperance Movement allowed ice cream treats, especially ice cream sodas, to gain an even more prominent place in American life, serving as an alternative to alcohol, a trend that lasted through Prohibition.

Fancy, molded ice creams weren’t for everybody. The ingredients for the frozen dessert were expensive, namely salt and sugar, and a lot of care and time had to be put into shaping the cream and making sure it froze and remained frozen. The beautifully plated desserts were then consumed in high-class social settings like pleasure gardens, expensive restaurants, banquets and dinner parties.

In cities, street vendors sold cheaper ice cream with lower quality ingredients, often called “hokey-pokey” (for reasons not entirely known) to poorer classes, but without any of the elaborate presentation that the wealthy enjoyed. This was before the cone, the ice cream sandwich and ice cream bars, so vendors would simply scoop the treat into a shared cup and when one customer was finished, they would give it back to the vendor who would use it to serve the next guest.

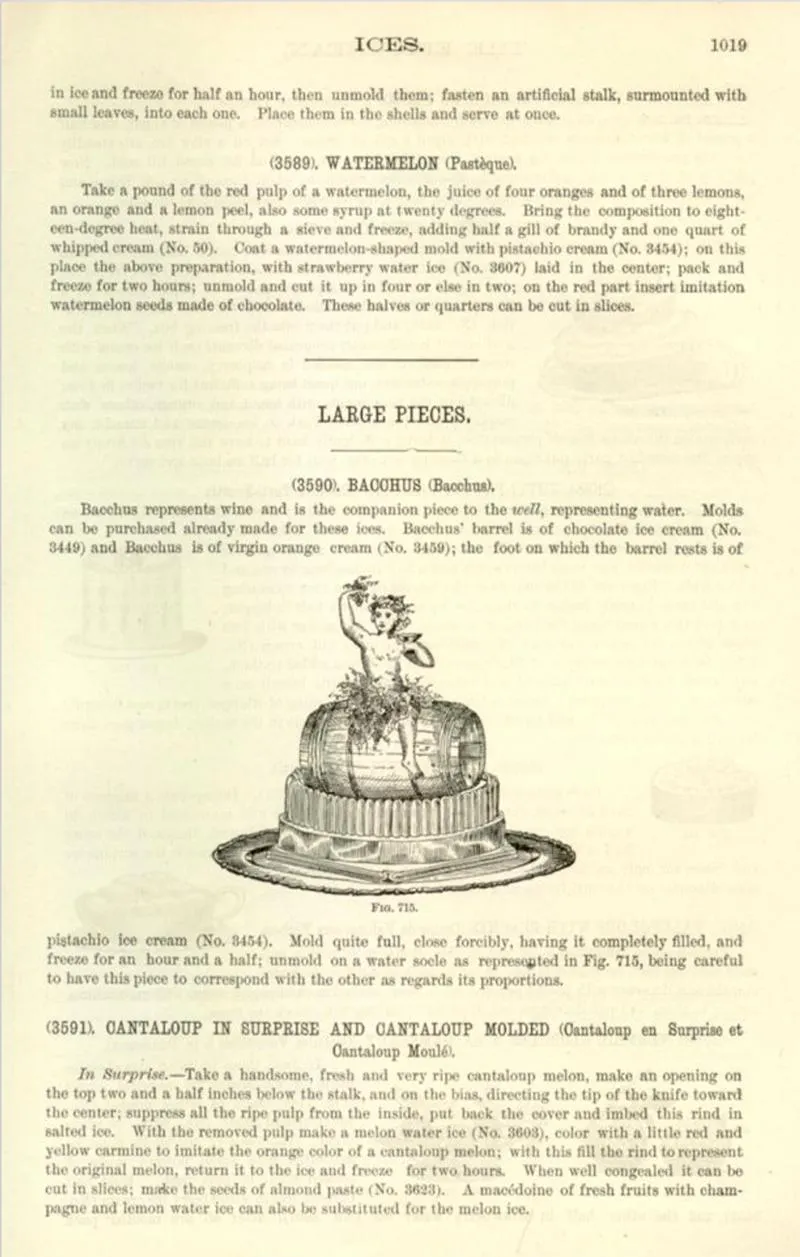

But among the elite, beautifully plated ice cream was an expectation. “If you were going to Delmonico’s [in New York City] in the late 19th century you expected something pretty spectacular whether it was ice cream or jellies or whatever it was,” says Quinzio. “Presentation was incredibly important.” An 1894 culinary oeuvre, The Epicurean, from Delmonico’s chef Charles Ranhofer outlines instructions for various molded dessert creations. Among the more modest ones are ices and ice creams shaped like a flower pot, dice, dominos, cards, strawberries, mushrooms and, of course, the oddly popular bunch of asparagus. The larger-scale masterpieces include a hen with chicks, a pineapple, a brick well and the Roman God of wine Bacchus, atop a wine barrel. For the dice, instructions say to fill two-inch cube-shaped molds with hazelnut ice cream and use “small chocolate pastilles three-sixths an inch in diameter” to create the dotted pattern. For the pineapple, pistachio ice cream is recommended for the stalk and Andalusian ice cream, “colored a reddish-yellow,” is suggested for the fruit’s meat. Like many of the dessert creations in the book, both are stuffed with alcoholic temptations: maraschino macaroons in the dice and an alcoholic mixture of the tropical fruit, biscuits and macaroons in the pineapple.

Day-to-day, molded ice cream had a less extravagant presence. In August 1895, a fashion brief in the The Philadelphia Times talks about “New and popular Ice cream molds” in the shapes of “[a] Trilby, Napoleon, Uncle Sam and the bicycle.” It notes that each caterer has a particular flavor to fill each mold.

Ice cream molds were used in households as well. A mold was a practical way to freeze ice cream, and home cooks experimented with various shapes as an impressive way to serve the treat to their guests. In the summer of 1886, a Lexington, Missouri newspaper advertised “moulded ice cream” at a local ice cream parlor for four weeks in a row. But those same editions also advertise the molds for purchase in the shapes of “pyramids, ornamented bricks, melons, horse shoes, Turk’s heads, individuals, etc.” explaining, “they will set off your table if you want to ornament it.” An 1891 frozen dessert cookbook, The Book of Ices, says molds and shapes “are made in a bewildering variety,” noting “[t]he most desirable are: A round one, an egg, or oval (cabinet pudding shape), an oblong (properly, “the brick”), the pyramid and “the rockery” (moule au rocher), an irregularly surfaced mound.”

In the early 20th century, ice cream cones and bars burst onto the scene. Good Humor trucks traveled from neighborhood to neighborhood selling ice cream on a stick and pastry cones became an easy grab-and-go option with minimal clean-up. On top of that, innovations in refrigeration and a surplus of dairy during World War I allowed ice cream prices to drop. With these convenient and affordable treats, there was less of an impetus for home cooks or restaurants to make their own ice cream desserts. Molds transitioned into novelty items with retailers advertising holiday-inspired shapes for Valentine’s Day, St. Patrick’s Day, Easter, Halloween, Thanksgiving and Christmas. Newspapers in Burlington, Vermont in 1904 advertised “[L]ilies, chickens, rabbits and little nests” for Easter. Valentine’s Day ads that ran in Salt Lake City in 1920 touted “Heart or Cupid designs,” and “Pumpkins, Apples, Turkeys, Footballs” sold for Thanksgiving in Valparaiso, Indiana in 1930.

“Monday will be Armistice Day,” reads a November 1929 Fossleman’s Ice Cream Company advertisement in the The Pasadena Post. “Are you entertaining? The suggestion of ice cream moulds of a flag and Uncle Sam will be most timely.” It goes on to advertise strutting turkeys, pumpkins and apple molds for the upcoming Thanksgiving holiday.

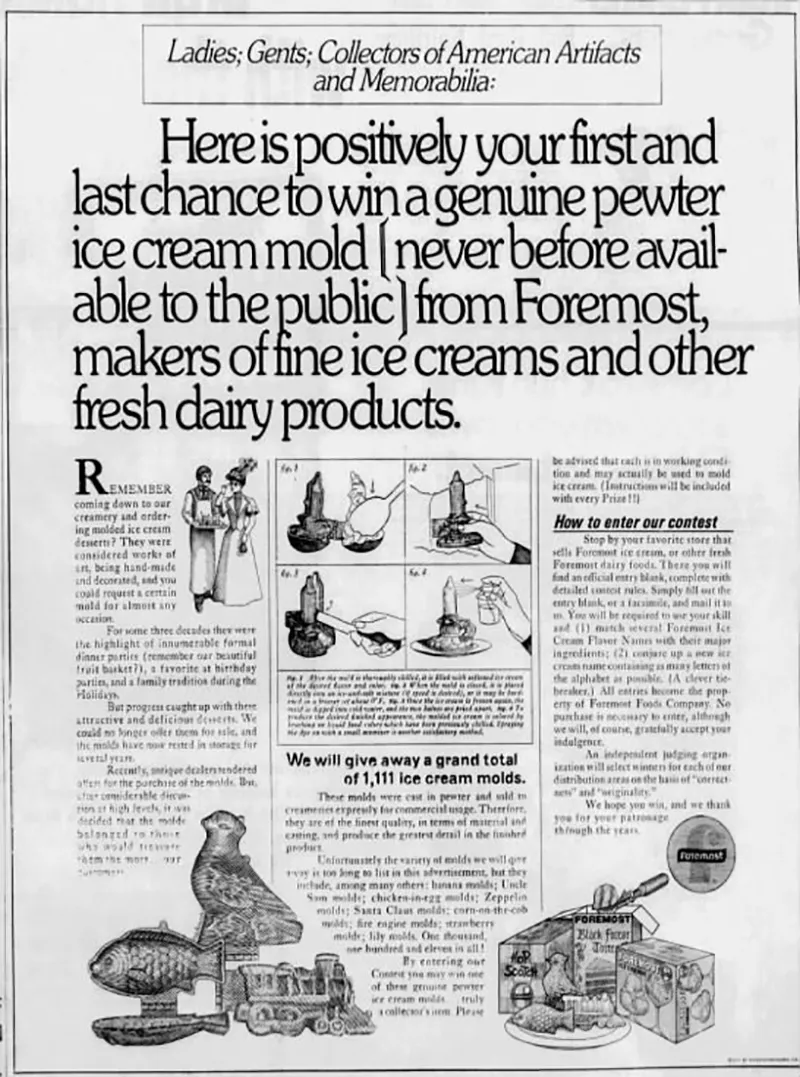

The fad lasted decades. As recently as 1965, an ice cream shop in Indianapolis, Indiana advertised Santa Claus and Christmas tree ice cream molds in the local newspaper, but that’s about when the tradition dies out. Just six years later, an ice cream manufacturer, Foremost, in Fort Worth, Texas held a contest to give away 1,111 molds that had been in storage for years. “Progress caught up with these attractive and delicious desserts and we could no longer offer them for sale,” the notice reads. The relics up for grabs included corn-on-the-cob, Uncle Sam, fire engine and Santa Claus molds.

The tradition of shaped ice cream now lives on in novelty items. In 2018, a London gelato chain’s avocado imposter gained internet fame. That same year, a cafe in Taiwan sold ice cream shaped like shar-pei puppies. Aldi grocery stores sold rose-shaped ice cream atop chocolate cones this spring. It seems we are not yet finished tricking the eye through ice cream.