Tea’s Time

The ancient drink makes a comeback

When Coca Cola and Nestlé recently unveiled their new beverage, Enviga, they confirmed the standing of Camellia sinensis, better known as the tea plant, as the comeback kid of beverages. Five thousand years after Chinese emperors claimed it as their own, 800 years after the Japanese made drinking it an art form, 340 years after the Dutch went crazy over it, 280 years after the English named a meal after it, and 234 years after the Americans heralded a revolution with it, here comes tea, reinventing itself again into a commercial power house.

U.S. sales of tea rose from about two billion dollars in 1990, to well over six billion in 2005; they could reach ten billion by 2010. Supermarkets are offering dizzying choices, teashops are sprouting all over and even Starbucks and Dunkin' Donuts, those barometers of American Zeitgeist, have come up with their own tea concoctions.

Tea's long-touted health benefits, which range from increasing mental alertness to fighting a variety of cancers, have fueled some of the upsurge, says Joseph Simrany, president of the Tea Association of the U.S.A. But a primary reason for the drink's newfound popularity is convenience. "Consumer needs change," Simrany says. "People don't have enough time, and cans and bottles are the response. These are expanding the market for tea."

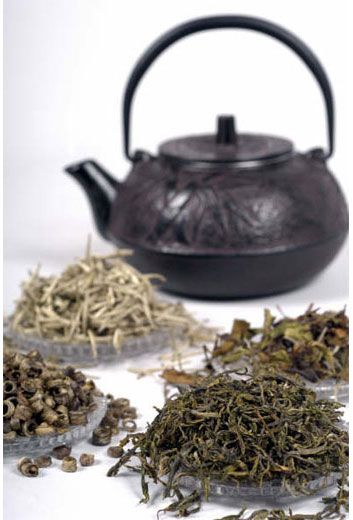

And to think that in its early days, tea was associated with the serene rites of Zen Buddhism, and that it was drunk from vessels made out of the finest earthenware, porcelain and silver then available.

Legend has it that the beverage was discovered by Chinese emperor Shen Nung around 2800 B.C., when some leaves from the tea plant fell into the water that servants were boiling for him. While the story may be apocryphal, there is no doubt about tea's influence on China's social and cultural fabric. Over successive centuries, poets and musicians extolled its benefits, potters fashioned implements for its consumption and artists painted idyllic scenes of tea partaking. In 780 A.D., the Buddhist-educated scholar Lu Yu penned Ch'a Ching, a comprehensive work on cultivating, brewing and drinking tea that became the standard for tea ceremonies in other Asian countries, especially Japan.

Although some Japanese Buddhist monks are said to have used tea as early as the 7th century to keep themselves awake during meditation—a secret learned from their Chinese counterparts—tea adulation didn't seize Japan until the 13th century, after a Zen Buddhist master brought back some tea seeds for planting.

Over the next 400 years, Zen Buddhists perfected the exquisitely ritualistic tea ceremony, cha-no-yu, (literally, hot water for tea), prescribing every aspect of the occasion from the sitting order of the participants to the implements to be used. "Tea Bowls in Bloom," a tea exhibit that runs through July 15 at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., shows how tea forged an alliance with art. It is credited with helping the Japanese discover a key aesthetic: their love of imperfection. Unlike the symmetrical, perfect teaware favored by the Chinese, the Japanese found they preferred uneven, seemingly flawed bowls and water jars—each item unique.

While it was the Portuguese who first brought tea to Europe, it was Dutch traders who turned it into a craze. In 17th-century Hague, the prosperous had tearooms in their homes and paid upwards of $100 a pound for tea, pouring their brew from Delft teapots with Chinese motifs.

In England, too, tea was initially the delight of the elite classes—so expensive that it was kept under lock and key in elegant tea caddies. As prices dropped, tea made its way down the social ladder, but it abided by the class structure. The well-to-do had "Low Tea," served mid-afternoon and accompanied by savories such as scones and dainty sandwiches; the working classes had "High Tea," their main meal, served at the end of the working day, around 6 p.m. Coffee houses (coffee arrived in England before tea) became tea shops, so busy that patrons had to pay a little something extra to get served—thus tips were born.

Not surprisingly, Americans have had a less reverential relationship with tea. They dumped 300 cases of it in Boston Harbor in 1773, and moved on to invent iced tea (1904) and the tea bag (1908). Tea bags came about when the clients of tea merchant Thomas Sullivan assumed that the small silken bags in which he shipped tea were supposed to be put straight into the pot.

Does the arrival of tea-filled bottles and cans mean that this is the end of the line for traditional tea enjoyment? Hardly. Specialty teas are also booming. Tea connoisseurs are becoming as particular as wine aficionados, asking not just for generic tea but for tea from a specific country—even, a specific tea estate. Kenilworth, a black tea grown in Sri Lanka, and Makaibari, an Indian Darjeeling, are among the most popular. Also gaining a greater audience is white tea—picked before the leaves are fully opened while the buds are still covered by fine white hair, which can command prices up to $200 a pound. As Simrany says, "only one logical conclusion seems possible: The future for tea in the United States looks very hot indeed!"