OFFICE OF ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS AND INTERNSHIPS

Steeped in Memory: Amelia Joe-Chandler’s Hogan Teapot at NMAI

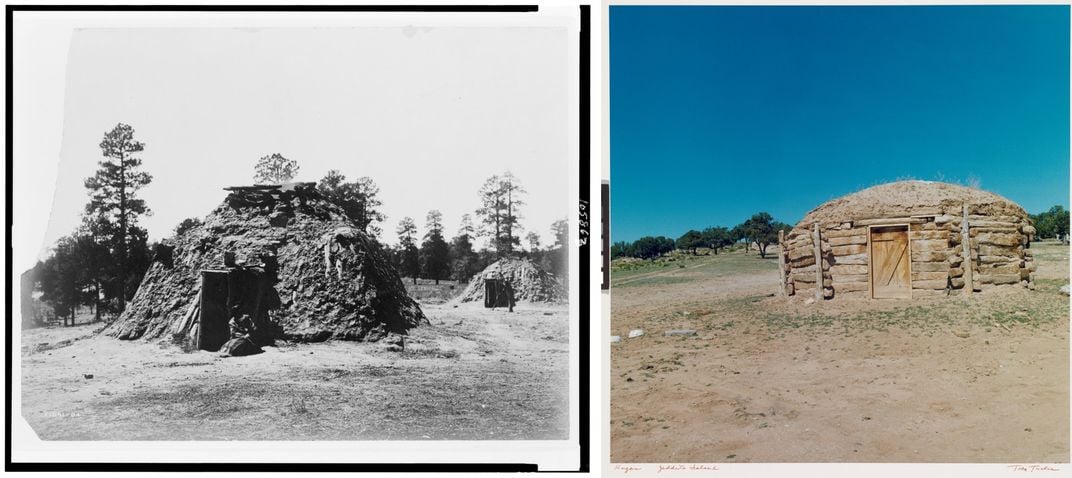

Nestled in an archival box in the storage vaults of the National Museum of the American Indian, I encountered a small, copper sculpture that points to an entirely different sense of place. Hogan Teapot (2013) by Diné (Navajo) artist Amelia Joe-Chandler is a living homage to the idea of home—particularly her family’s home in Dinétah, the ancestral homelands of the Navajo Nation in the American Southwest. The brilliancy of the copper recalls the traditional form of the hogan, a dome-shaped structure with a log or stone framework that is traditionally covered with mud that hardens like rock. With a door outlined in silver on the side, the lid handle as a stove pipe, and a cast tree and two small sheep as the handle, Joe-Chandler’s sculpture changes the ubiquitous form of the teapot into a site of personal encounter through these allusions to her family’s home.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Teapot.2013.hand_PRIMARY.JPG)

Nestled in an archival box in the storage vaults of the National Museum of the American Indian, I encountered a small, copper sculpture that points to an entirely different sense of place. Hogan Teapot (2013) by Diné (Navajo) artist Amelia Joe-Chandler is a living homage to the idea of home—particularly her family’s home in Dinétah, the ancestral homelands of the Navajo Nation in the American Southwest. The brilliancy of the copper recalls the traditional form of the hogan, a dome-shaped structure with a log or stone framework that is traditionally covered with mud that hardens like rock. With a door outlined in silver on the side, the lid handle as a stove pipe, and a cast tree and two small sheep as the handle, Joe-Chandler’s sculpture changes the ubiquitous form of the teapot into a site of personal encounter through these allusions to her family’s home.

Of the todich’iinnii (Bitterwater) clan born for the hast łish nii (Mud) clan, Joe-Chandler was introduced to a range of art forms during her childhood. She learned the art of sandpainting and silversmithing from both of her parents, who produced works for local trading posts. At the age of nine, she wove a small rug over a summer. Around the age of twelve, Joe-Chandler started to work alongside her father, aiding in his jewelry production. In the 1980s, she attended New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, where she pursued a degree in arts education with a focus on metalsmithing. Having been around jewelers her whole life, she already understood how metals react: the challenges of sawing a straight line, how and when to anneal silver, the very moment when solder flows. Her metalsmithing professor, Kate Wagle, encouraged her to design pieces on a larger scale with aluminum, experimenting with textures while learning the art of hammer raising. She then pursued graduate work at Indiana University-Bloomington, where she studied the traditional techniques of Asian teapots under Professor Randy Long. According to Long, “Amelia Joe-Chandler is one [of my] most creative, original, and dedicated metalsmithing and jewelry students … When I showed slides for inspiring students to make creative teapots and I showed them some of my collection of Chinese Yixing clay teapots, Amelia was inspired to make a hogan teapot.”[1] Joe-Chandler started to develop her hogan forms through sketches, mockups, and plaster maquettes, carefully considering how to properly translate her ideas into metal. This was not only a formal challenge, but also a mode of fending off homesickness while away at school. In Indiana, she was able to think deeply about her Navajo philosophy outside of the sacred mountain range of Dinétah.

Joe-Chandler’s work is informed by the Diné concept of hózhó, the notion of internal and external balance at the center of the Navajo Philosophy of Life. This philosophy honors the connections between air, fire, water, and earth, which Joe-Chandler meditates on while thinking through her designs. Earth provides the metal, air feeds the fire to work the metal, and water cleanses and cools it. Hózhó, or “to walk in beauty” in Diné, expresses a notion of harmony and balance between and among people, animals, and the environment.[2] Through our conversations, Joe-Chandler taught me that life has both positive and negative energies, and hozhó is a state where both are in balance. “Creating hozhó means you create when you are a balanced human being, doing well, and are capable of putting that balance into the piece.” This is not just about design—or the perception of beauty in a finished artwork—but intimately connected with the process of creating, including the process of raising copper into the domed form through hammering. “Every artist puts something into their work: time, energy, sweat. Hammering is a process that reflects your thoughts; your thinking process about it.” For Joe-Chandler, objects lock memories in time—both the spiritual and the cognitive. She taught me that even anger and frustration can appear in a work if the artist is not in balance. Part of the artistic and human process is working through emotions, coming to an internal balance, and letting them go by selling or giving away the artwork. Hozhó is not just at the heart of the process; her Diné philosophy lives in the metal she has worked.

The Smithsonian’s Hogan Teapot is the very marriage of form and utility. The copper color recalls the earth tones of mud that characterize the round, traditional hogan form.[3] When Joe-Chandler cites the structural form of the traditional hogan, her reference provokes ideas beyond the visual. I asked about the meaning of the hogan and Joe-Chandler immediately placed it not in space but in time: it is the start of life—the place where one is born or a representation of the birthing process—as well as the end. It is not just a place that is made, but a place where one can always be in the state of making or becoming.

This theme of becoming is also reflected in the utility of the teapot itself, which can hold about one and a half cups of tea. The very history of tea and teapots is part of the colonial American origin story with the Boston Tea Party, the stories of the silversmith Paul Revere, and remote or distant global networks of the tea trade. Yet within the specific context of Dinétah, tea is about knowing and honoring the local. Navajo tea is deeply rooted in a sense of place and connection to the immediate land. Diné herbalists and diagnosticians possess a deep knowledge of plant life in the mountain desert—often dismissed as barren to the foreign eye—and navigate the complex ecosystem of herbs for healing. As knowledge under the care and collection of a medicine man, one often drinks herbal tea for its healing qualities, from the aching back to diabetes.[4] Special medicine hogans also operate as sites of ceremony for the curing of the body as well as a site of prayer. The hogan is not just a space of healing, but also a place where community members can come together and recount histories over a cup of tea or coffee.

In the Smithsonian’s Hogan Teapot, two sheep are placed beside a silver tree to form the teapot’s handle. When asked about the importance of the sheep, Joe-Chandler mentioned that sheep represent security and wellbeing for a family. Sheep provide food, wool for a rug, or could be bartered in times of need. Even the traditional weaving looms used by Diné women could be created with any tree trunk. Introduced by Spanish settlers in North America, sheep have been at the center of Diné life and art, from the world-famous blankets spun from wool to a staple of the Southwestern economy that allowed the Diné to trade among the Pueblos. The need for grazing grounds operated at the center of the community’s efforts to reclaim land after the Navajo Nation’s return from the Long Walk and internment by the U.S. Government at the Bosque Redondo Reservation (1864-1868).[5] Sheep are central to Joe-Chandler’s family history. Her maternal great-grandfather was a medicine man, and her grandmother was a midwife. Many gave her grandmother a lamb after the birth of their children instead of money, because people often had none. Silver was also gifted to medicine men in the form of jewelry, adding a material meaning of wealth to the small figurines. The female weavers on her father’s side of the family work closely with sheep-herding families. Thus, the handle goes beyond ornamentation, honoring the connections and dependencies between people that have come to shape Joe-Chandler’s personal story.

Art is not only a personal form of healing and remembrance, but also Joe-Chandler’s way to help others process their own memories. Hogan Teapot provides a node of connection for others to work through the memories of love, loss, and happiness that connect us to one another across geography and time. Her teapots echo a deep commitment to revealing connections between herself and land, the artist and viewer, the server and guest, all of which speak to a fundamental sense of humanity and the basic human experience.

This blogpost was based on a phone conversation between the artist and writer on Saturday, September 5 and Saturday, September 26, 2020. Research for this piece was also supported by the Center for Craft, Creativity, and Design in Asheville, North Carolina.

[1] Randy Long, email message to author, December 3, 2020.

[2] For more on the meaning of hózhó, see Larry W. Emerson, “Diné Culture, Decolonization, and the Politics of Hózhó,” in Diné Perspectives: Revitalizing and Reclaiming Navajo Thought, ed. Lloyd L Lee and Gregory Cajete (Tuscan, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2014), 49–67; Vincent Werito, “Understanding Hózhó to Achieve Critical Consciousness: A Contemporary Diné Interpretation of the Philisophical Principles of Hózhó,” in Diné Perspectives: Revitalizing and Reclaiming Navajo Thought, ed. Lloyd L Lee and Gregory Cajete (Tuscan, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2014), 25–38; and Gary Witherspoon, Language and Art in the Navajo Universe (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1977), 151-154.

[3] Anthropologist Kerry Frances Thompson summarizes the centrality of the hogan and its connection to the concept of hózhó as follows: “A hogan is situated in a landscape given meaning and order by four sacred directions that transcend the physicality of the earthly plane. It is a sacred space in the sense that it is the physical locus from which one pursues hózhó in everyday life. One also performs the ceremonies to seek blessings and assistance from diyin dine’é, when the need arises, in a hogan. The tangible outcomes of the practice of Navajo philosophy that may be investigated archaeologically therefore include the hogan and its physical attributes.” See Kerry Frances Thompson, “Ałkidá¸á¸’ Da Hooghanée (They Used to Live Here): An Archaeological Study of Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Navajo Hogan Households and Federal Indian Policy” (Ph.D., Tuscan, AZ, The University of Arizona, 2009), 98-106

[4] For more on Navajo tea, see Charlotte J. Frisbie, Tall Woman, and Augusta Sandoval, Food Sovereignty the Navajo Way: Cooking with Tall Woman (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2018), 244-6; also see Lela Nargi, “For Navajos, Desert ‘Tea’ Fosters Kinship with Heritage and Nature,” The Salt-NPR (August 29, 2017), https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/08/29/546817827/for-navajos-desert-tea-fosters-kinship-with-heritage-and-nature.

[5] For more information on this history, I highly recommend the writings by Jennifer Nez Denetdale (Diné/Navajo), a Professor of American Studies at the University of New Mexico, particularly Reclaiming Diné History: the legacies of Navajo Chief Manuelito and Juanita (Tuscan: University of Arizona, 2008) and The Long Walk: the forced Navajo Exile (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2008).