OFFICE OF ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS AND INTERNSHIPS

The Zine Teens Take on Girlhood

Each day, the National Museum of American History (NMAH) receives hundreds—sometimes thousands—of teenage visitors. Teens wearing bucket hats; groups in matching t-shirts; groups that are aggressively rude to staff in the elevators. But while the museum succeeds in many things, it does not necessarily engage well with youth

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/A1.1_Intro_final_SM.jpg)

Each day, the National Museum of American History (NMAH) receives hundreds—sometimes thousands—of teenage visitors. Teens wearing bucket hats; groups in matching t-shirts; groups that are aggressively rude to staff in the elevators. But while the museum succeeds in many things, it does not necessarily engage well with youth. My own survey of the museum floor demonstrated that across dozens of exhibitions and displays, only four featured stories about youth — and of these, only one was designed with youth as the primary focus.[1] The upcoming exhibition Girlhood (It’s complicated) responds to this absence, using girls as a lens through which to understand women’s history. NMAH is currently undergoing a messaging shift in an effort to establish itself as the most accessible, inclusive, and relevant history museum in the nation. It is critical that this process includes the museum’s teenage visitors. During my fellowship, I used the pre-opening of Girlhood to explore how the museum can engage better with teenage visitors about new exhibitions.

In a series of informal listening sessions held at the museum, teenagers reported wanting to see more stories about people their age represented on the museum floor — not as future important figures, but as people who are doing important things right now. Although they have often been overlooked in history books, girls have a long history of political and social action. Girls are increasingly being recognized as artists and activists and the leaders of social movements, and this exhibition celebrates the power and influence of girls on shaping American politics and communities.

My fellowship focused on direct interaction and authentic communication with teens.[2] Authentic work, as defined by the Whitney Museum’s “Room to Rise” report, involves direct interaction, collaborative projects, and reflective practices. This project took several forms. On a macro scale, I’m developing an initiative to partner with teen girl social media influencers to create exhibition preview content. On a micro scale, I partnered with a group of DC high school students to create an exhibition “zine.” In both cases, the goal was to create resources with teens, not just for them — I wanted to work with teens as active partners to create something purposeful and relevant.

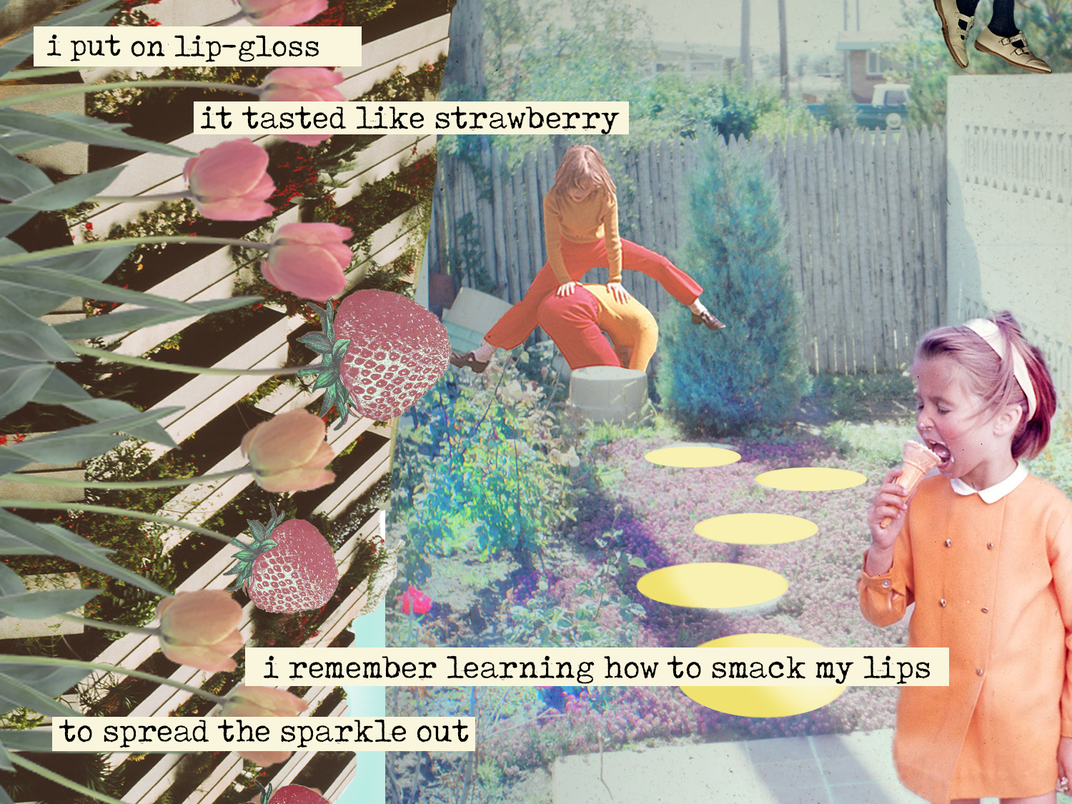

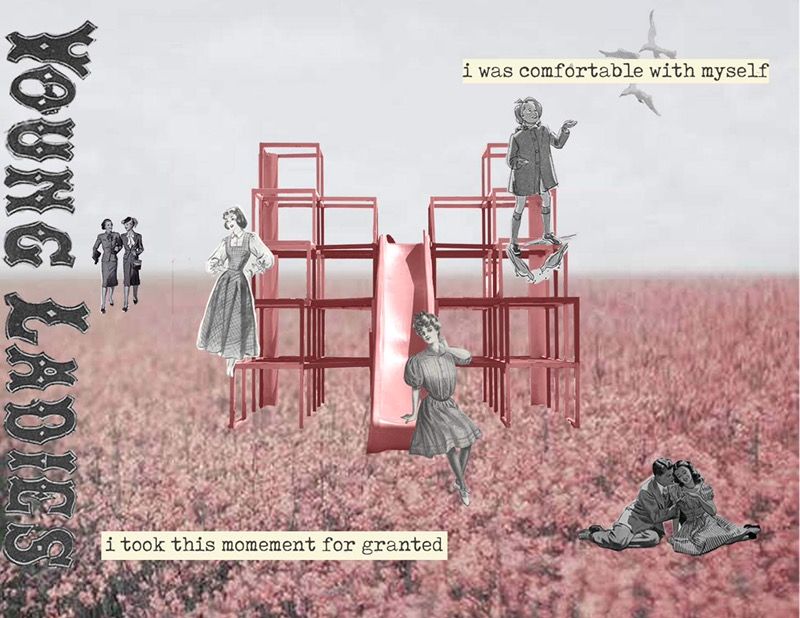

Since February, I’ve been conducting a series of zine workshops with a group of six high school students at DC charter School Without Walls. (Briefly, a zine is a noncommercial, often self-published or online publication usually devoted to specialized or unconventional subject matter. Zines have historically been created and distributed by girls, people of color, and other marginalized groups to create their own information channels as publishing is often controlled by older, white men. Zines are often, though not always, folded in a particular way that creates a booklet from a single sheet of paper without necessitating staples). Girlhood is designed to look and feel like a zine, so I decided to partner with a group of actual teen girls to create a companion zine for the exhibition. It was important to me that teens be at the center of creating exhibition resources for other teens in a youth-focused exhibition — they are able to communicate with other teens on a peer-to-peer level.

I provided historical background on the stories and objects from the exhibition — the zine is grounded in the way that the history of girlhood interacts with the students’ contemporary experiences as girls. We also visited the zine collection at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. This visit provided both thematic and aesthetic inspiration — zines ranged from pocket-sized single sheets of paper to professionally printed booklets, and from penciled stick figures to photo-copier collages to oil paint. The group decided on collage as their medium, to maximize cohesion, and pulled from historic advertisements and magazines to create the spreads in Photoshop.

Throughout the process, I was struck by how thorough and thoughtful my students were with the subject material. They were conscious of the intersections between race, class, and gender identity in ways that I certainly wasn’t as a teenager. The group was very aware of being mostly white and cis-gendered, and decided to conduct interviews with their peers to gain a fuller picture of girlhood experiences. They created a series of 14 interview questions, ranging from “What’s your favorite thing about yourself?” to “When do you think your childhood ended?” Using quotes and recurring images pulled from the responses, they collaged together the pages of the zine.

But what struck me the most was the way the group split up the zine into life “stages” — each spread represents a different stage in a girl’s life. The girls split the zine into “childhood,” “in-between time” (late elementary and middle school), and adolescence (the “right now”). Everything else—the entirety of life beyond high school—was just “the future.”

To many teens, almost all of the stories told on the museum floor are about people in the “future” stage. While these stories are of course important to tell, teens’ lived experiences often go unrepresented. NMAH wants to become the most accessible, inclusive, and relevant history museum in the nation over the next 10 years — but if the museum does not work to include youth perspectives and programming at every level, it will never feel relevant to a large swath of our visitors. Youth is an incredibly dynamic time in the formation of civic identity and sense of self. The museum has a unique ability to promote learning and civic engagement, and thus has a responsibility to engage the next generation of Americans about our history.

Working better with teenagers doesn’t begin and end with one group of students or one exhibition. Girlhood will be on display at the museum for two years and then travel the country with the Smithsonian Travelling Exhibition Service. It’s clear that the museum can do more to engage young people. The museum’s existing youth engagement efforts are amazing: the annual youth summit draws thousands of attendees around a historic theme, interactives in Unity Square give young people the words for hard conversations. I’m amazed by the exhibition resource my zine teens created — they made something that their peers would respond to instead of adults guessing what teenagers might want and creating it for them. Teens are capable of a lot more than we often give them credit for, and sustained youth engagement is critical to the future of the museum.

[1] The exhibition Unity Square features the iconic Greensboro Lunch Counter and tells the story of the student sit-in protests that spurred on the civil-rights movement. Interactives throughout the exhibition emphasize civic engagement and were designed with middle and high-schoolers as the primary intended audience.

[2] The Whitney Museum’s “Room to Rise” report demonstrates that direct interaction with teens in museum settings has a significant impact on measures of civic engagement. These findings have been replicated in a SOAR study on visitor interaction with Unity Square.