How Art and Metaphor Help Students Unpack Complex Ideas

Smithsonian educators share how they frame artworks to explore complex ideas with students.

:focal(990x620:991x621)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/SAAM-2017.40_1.jpg)

Smithsonian educators share how they frame artworks to explore complex ideas with students.

As educators at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery, we use artworks as windows onto big ideas and scaffolds upon which to build understanding of complex issues. We often invite learners to think about these artworks metaphorically.

Metaphors simultaneously make the familiar unfamiliar and make more familiar certain unfamiliar things. They become powerful learning tools when we, standing alongside learners whose perspectives differ from our own, are stretched to find commonalities amongst our varied interpretations of these artworks. In so doing, we all see the organizing structures underpinning them more clearly. To explore this idea, we offer you two artworks that might initially seem dissimilar yet can be connected when we view them as metaphors for community.

Theaster Gates’s Ground rules. Free throw feels instantly familiar, and yet simultaneously disorienting. As you look at it closely, you realize it’s made of wooden floorboards that have been scratched, scuffed, and dented, speckled with colorful pieces of tape. You might begin to visualize the fast-moving sneakers that might have created those scuffs over many years and remember the gym classes of your youth. The boards have been shuffled, however, and any boundaries once defined by the tape are obscured.

Gates created this artwork in 2015 using gymnasium floorboards salvaged from decommissioned high school buildings in his home city of Chicago. Dozens of public schools in Chicago, deemed “underperforming,” have been closed as part of reform efforts in recent years. These closures disproportionately affected schools in under resourced, predominantly African American neighborhoods.

Considering this piece metaphorically opens up several intriguing lines of thinking. What does a school gym represent in American culture? We might think of it as a place where we learn to work together as a team, play by a shared set of rules, and gather to show support for our school and community. When a community loses a space like this, what happens to the people and neighborhood it once served? These questions allow us to make connections to social issues that are anything but simple.

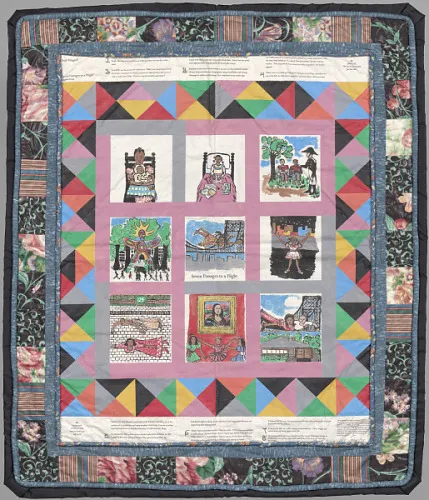

Next, take a close look at Faith Ringgold’s 1998 self-portrait quilt and accompanying artist’s book, Seven Passages to a Flight. Draw your attention to the visual elements of this self-portrait — the fabric, colors, patterns, writing, and small vignettes. What themes emerge as you observe this artwork? In order to convey her own experiences and those of other African American women in her story quilts, Ringgold drew inspiration from Tibetan "tanka" paintings, African piece work, and black American quilting traditions. In this artwork, the artist explores African American histories through recognizable faces, such as Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson, and autobiographical memories of her childhood in Harlem, NY, combining actual events, fantasy, and history.

An activist for racial and gender equality, Ringgold depicts herself flying as a metaphor for overcoming the challenges she had encountered as a Black woman. She hopes others will make personal connections in order to find their own story. The bridge, which she could see from her tar-covered Harlem rooftop, symbolizes opportunity. "Anyone can fly," she writes in her children’s book, Tar Beach. "All you have to do is have somewhere to go that you can’t get to any other way." The imagery of flying, Ringgold has explained, "is about achieving a seemingly impossible goal with no more guarantee of success than an avowed commitment to do it."

Ringgold’s quilted works call our attention to tradition, warmth, and family spaces. In them, she literally sews together scenes that build a story of aspiration and self-determination. She passes this legacy on to younger generations.

In comparison, Gates’s repurposed and jumbled floorboards serve to highlight the absence of the children they once supported, and the loss of a space where those children learned to become teammates and leaders.

In each of these artworks, the artists have taken small pieces and assembled them into something wholly different. Each material is imbued with its own distinct history that the artist uses to add depth of meaning to the finished work. When we look at these two works together through the lens of metaphor, we’re challenged to consider what makes a nurturing community, and the complexities of sustaining it. We may bring our own personal experiences to bear, then spiral our thinking outward to the wider world.

Transfer is a pedagogical ideal that helps students take the learning and thinking they’ve done in the classroom (or museum) with them into the real world. Metaphors prime our brains to seek similarities and structures while giving us permission to envision something entirely new. Making best use of artworks’ open-endedness, they free us to explore multiple interpretations while also challenging us to think critically and flexibly.

Learning in this way is quite like life: when presented with a messy and possibly contradictory knot of opinions and requests, we (hopefully) turn to one another and collaboratively chart a course based on our lived experience, prior knowledge, and reading of the land around us.