Reunited And It Feels So Good

Heard Museum exhibition tells the little-known story of one of the 20th century’s greatest artists and his connection to the indigenous people of the Arctic.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/M32.jpg)

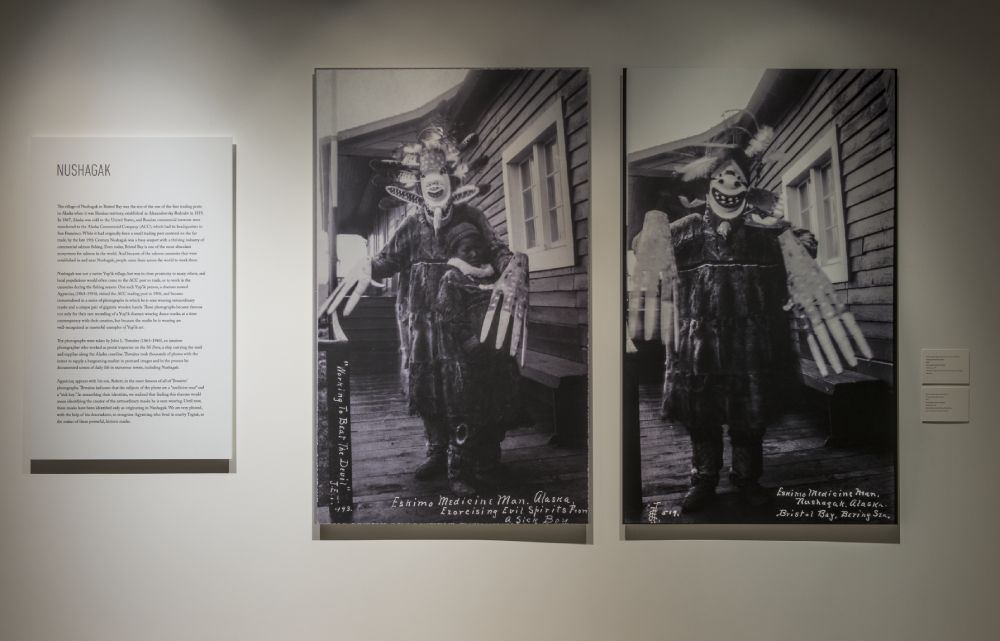

The original and groundbreaking exhibition, Yua: Henri Matisse and the Inner Arctic Spirit, organized by the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, told the little-known story of one of the 20th century’s greatest artists and his connection to the indigenous people of the Arctic. Yua is a Yup’ik (Alaska Native) word that represents the spiritual interconnectedness of all things and it runs like a thread through this vast story that spans centuries, continents, and cultures. It also captures the exhibition’s thematic essence, which is to celebrate the creative spirit that unites us all.

Henri Matisse (1869–1954) is celebrated for his sensuous approach to color and composition. But largely unknown to the general public is that in the last decade of his life, while working on his masterpiece, La Chapelle de Vence, Matisse became interested in both the physical forms and spiritual concerns of the Inuit people, which, in turn, led him to create a series of 39 individual portraits depicting Inuit faces.

These striking black-and-white images were inspired, in part, by a group of Yup’ik masks collected by Matisse’s son-in-law, Georges Duthuit. It’s remarkable to see the portraits next to the masks that inspired them and give viewers the rare chance to see masterpieces from different cultures side by side.

One of several important discoveries resulting from the research conducted for this exhibition by the co-curators, Sean Mooney and Yup’ik elder Chuna McIntyre, is that we now have names for the makers of many of the masks in the exhibition from major institutions around the world, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

The five critical loans from the National Museum of the American Indian are masks made by a shaman that we now know was called Ikamrailnguq, also known as Wassily.

Recognizing the name of the maker of these masks upends the common museum practice of simply associating an object of Native manufacture with its originating tribe. This exciting advance in scholarship encourages viewers to regard these masks in a new light: to see them not as ethnographic objects made by faceless people, but as the creative expressions of specific individuals whose work is as worthy of consideration as that of other great artists. In the exhibition, we explored for the first time the qualities that masks by Ikamrailnguq share with the work of Matisse from a Yup’ik perspective, and came to appreciate that the two artists were contemporaries.

The Ikamrailnguq masks in the exhibition were made more than 100 years ago at Napaskiak, on the Kuskokwim River in southwestern Alaska, for social gatherings and ceremonies. Masks like these were traditionally made in pairs or related groups, but due to a variety of circumstances were often separated. A critical objective of this exhibition was to reunite as many of these pairs as possible so that we might better understand the meaning of these masks. We were, for example, able to reunite a qucillgam yua mask depicting a female sandhill crane spirit from the Smithsonian with its mate, which resides in the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York, after more than 100 years apart. The emotional force in seeing them together, reunited at long last after being separated by time and great distances, was undeniable and was also history in the making.

More than 40 Yup’ik masks were featured in the exhibition, long considered icons of American Indian art for their incredible sculptural qualities, psychological complexity and otherworldly beauty. It’s unlikely that there will be an assemblage of masks like this ever again.

The Heard Museum is a proud Smithsonian Affiliate, and we’re grateful to the National Museum of the American Indian for their collaboration, which considerably strengthened our exhibition. This exhibition closed February 3, 2019.