NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Fish Detective Solves a Shocking Case of Mistaken Identity

Smithsonian scientist David de Santana discovered two new species of electric eels in the Amazon rainforest.

:focal(229x145:230x146)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Electrophorus_Vari_2.jpg)

Electric eels captivate imaginations. They inspire scientific advancements, like the electrical battery, and add danger in fiction by granting superpowers to villains like Electro in The Amazing Spider-Man 2. But the public and even scientists have a lot to learn about these charged creatures. Smithsonian researcher David de Santana is on a mission to investigate the mysteries surrounding them and the other electric fish they are related to.

Becoming a fish detective

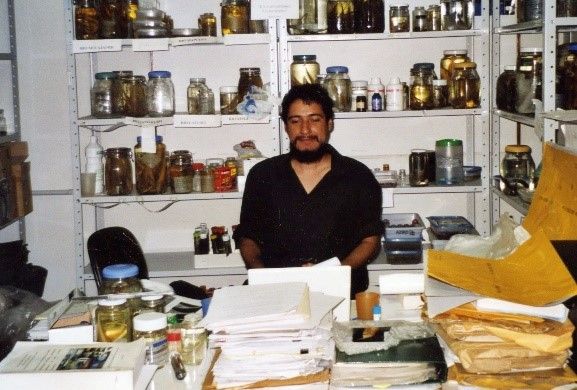

De Santana is a self-described “fish detective” who uncovers new species of South American knifefish — a group of freshwater fish that generate electricity for navigation, communication and, in the case of electric eels, for hunting and defense. His specialty grew from his childhood fascination with fish.

Growing up in Brazil, de Santana collected fish from Amazon streams on his grandparents’ farm to keep in aquariums. His curiosity never diminished, and he set his mind to a career working with fish. As he studied in college, he realized a lot about South American knifefish remained to be discovered.

“I remember I saw this report on black ghost knifefish — a very popular fish in the aquarium trade,” de Santana says. “Afterwards, I went to look up more about South American knifefishes and I couldn't find the basics, like how many species were out there or descriptions of their biology and behavior.”

So, he went searching for the elusive fish, which led him to the island of Marajó in the mouth of the Amazon River. He connected with a fisherman on the island who caught black ghost knifefish to export to aquariums. While living and working with the fisherman, de Santana caught many other electric fish that he was unable to identify based on the existing science.

That experience set him firmly on the path of studying knifefish. He eventually landed a pre-doctorial fellowship at the Smithsonian and then later a full-time, research position studying the fish. In his 16 years as an ichthyologist, de Santana has identified more than 80 new species of fish.

Rainforest for a lab

Tracking down these new species requires collaboration and grueling field work. In addition to collecting fish himself, de Santana also relies on many collaborators to send tissue samples to him at the Smithsonian. And like the fisherman on his first search for the black ghost knifefish, de Santana says that the local people are an invaluable source of information when he goes out looking for fish.

“The local people teach us a lot,” de Santana says. “It's interesting to talk with them and to listen, and to just to follow them because in the field they are the specialists.”

Even with a good team, fieldwork is challenging.

“Fieldtrips are one of hardest tasks in my work,” de Santana says. “When we go to the tropics we are in a dangerous environment.”

He says that the high temperature and humidity combined with rapidly running water or deep mud makes research difficult and tiring. In the field, De Santana often works 12 to 16 hours non-stop to collect the valuable data needed to definitively identify and document fish.

Documenting biological treasures

De Santana is currently leading a five-year project to describe species of knifefish and place them in the tree of life.

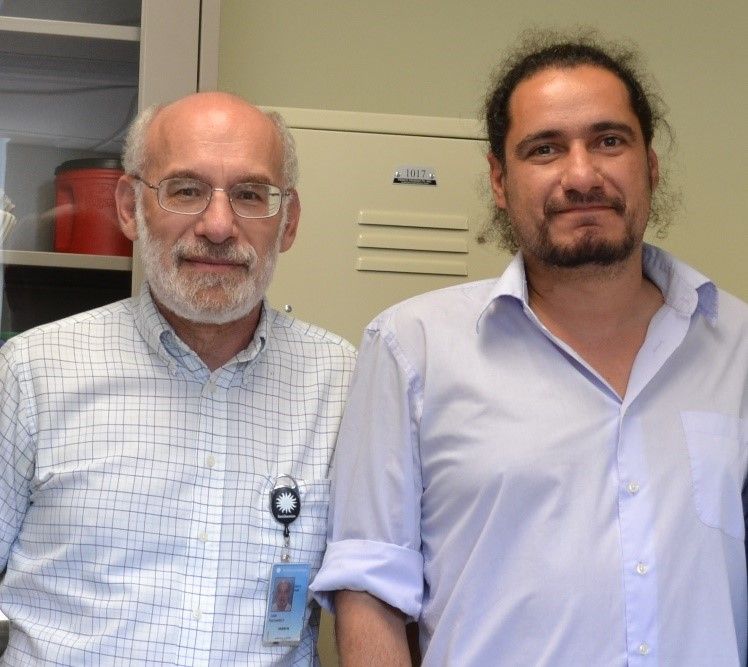

On September 10, De Santana and his colleagues described two new species of electric eel in the journal Nature Communications. One species is named Electrophorus voltai after Alessandro Volta who invented the first true electric battery with inspiration from electric eels, and the other is Electrophorus varii after de Santana’s late colleague Richard Vari.

The discovery is emblematic of the opportunities and importance of biodiversity research, even in large species that scientists thought had been understood for years.

“There are a lot of things out there to be discovered — not only in the Amazon rainforest, but the Congo rainforest and the Southeast Asia rainforest,” de Santana says. “And the human impact that you see in those regions is heartbreaking.”

He compares the destruction of these biodiversity hotspots, like the ongoing burning of the Amazon for example, to a library burning down without the books having been read. Such loss deprives us of deeper insights and valuable knowledge of the natural world that could lead to developments in medicine, technology and other societal applications. Based on his observations, de Santana thinks if current trends continue then in 50 or 60 years we will be left with mere fragments of the current wealth of biodiversity.

De Santana’s research project to explore the diversity of knifefish is planned to continue into 2022. The team aims to identify the range of voltages produced by each eel species, sequence the entire genome of Volta’s electric eel and study electric eel ecology and behavior. De Santana also expects that they will identify more distinct species during the project.

“Discovering new species is one of the more exciting parts of my work,” de Santana says. “In the case of the electric eels, discovering them and understanding the locations and environments that they live in was equally thrilling.”

Related stories:

Discovery and Danger: The Shocking Fishes of the Amazon’s Final Frontier

This Smithsonian Scientist is on a Mission to Make Leeches Less Scary

Why Aren’t St. Croix Ground Lizards on St. Croix?

Some Archaeological Dating can be as Simple as Flipping a Coin