NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Q&A: Sea Monsters in Our Ancient Oceans Were Strangely Familiar

Stunning fossils reveal that Angola’s ancient ocean ecosystem was at once strange and familiar.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/hsj_4367.jpg)

Between 1961 and 2002, Angola was virtually inaccessible to scientists while the country struggled with war and civil unrest. Now, sixteen years after peace was achieved, never-before-seen fossils excavated from Angola’s coast will be on display in a new exhibit, called “Sea Monsters Unearthed,” which will debut at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History on November 9.

In 2005, Louis Jacobs and Michael Polcyn, paleontologists at Southern Methodist University and collaborators on the exhibition, led the first major expedition in Angola since the acceptance of the plate tectonics theory in the mid-1960s. Dubbed Projecto PaleoAngola, the expedition looked to study the effects of the opening of the South Atlantic Ocean on life over the last 130 million years. The result? Stunning fossils that reveal how the ancient South Atlantic Ocean ecosystem was at once strange and familiar.

In the following interview, Jacobs and Polcyn tell us more about Angola’s ancient ocean, what once lived there and how its fossil record offers clues for the future.

Describe the opening of the South Atlantic Ocean

The formation of the South Atlantic is a complex geological story. Africa and South America were once one large landmass. Beginning about 134 million years ago, heat from deep within the Earth caused the landmass to split in two—a theory called plate tectonics—and drift apart gradually. This made way for a new ocean crust between the continents. As the next 50 million years passed, water began to flow freely and the new ocean grew wider, leaving us with the puzzle-like fit of Africa and South America separated by the South Atlantic Ocean that we recognize today.

Unlike the ocean today, Angola’s ancient ocean was full of mosasaurs. What were these strange sea monsters?

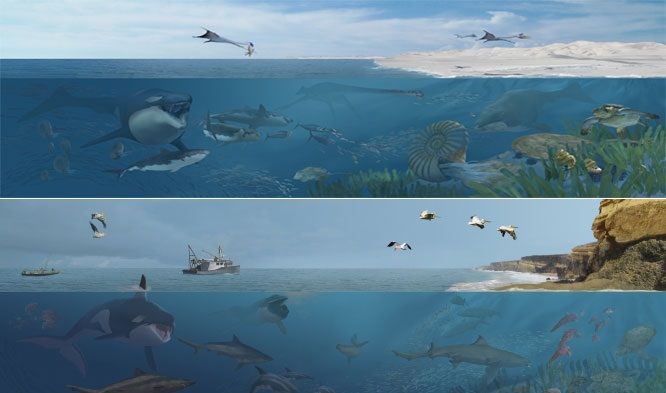

When the South Atlantic opened up, it created a new environment in which marine reptiles thrived. Mosasaurs—alongside marine turtles and plesiosaurs—were one of the major players in Angola’s Cretaceous marine ecosystem. They were giant, energetic marine reptiles that looked similar to today’s killer whales and dolphins except that the tail flukes in mosasaurs were like an upside-down shark tail.

Mosasaurs are a large and diverse group of ocean going lizards that existed for about 32 million years, going extinct with the dinosaurs. The earliest forms were small, about a yard long, but later descendants grew to 50 feet or more. Their diets varied widely from one species to the next. Some species, for example, had bulbous teeth and devoured huge oysters while others had slender teeth for snagging fish. The top predators amongst them had teeth that enabled them to eat whatever they could capture.

By the time mosasaurs went extinct about 66 million years ago, they lived around the globe in deep oceans, shallow inland seas and coastal shelves, feasting on different prey.

How do scientists know about these sea monsters?

We can’t observe mosasaurs’ behavior directly, so we study their fossils—how they look, where they were found, how old they are—to reconstruct the reptile and its environment and compare that bygone ecosystem to today’s ocean.

One of the most surprising fossils found in Angola, displayed in the exhibit as if it were in the ground, to mimick the moment it was discovered, had three other mosasaurs in its belly, providing four mosasaurs—of three different species—all for the price of one. Not only does this specimen document cannibalism, but it also shows that a diverse group of top consumers dominated the ecosystem. This indicates high productivity in this ancient community, similar to that of large marine ecosystems today.

It sounds like ancient oceans were vastly different from today’s oceans. Are there any similarities?

Cretaceous oceans certainly were different from modern oceans, especially when you compare the creatures dominating the waters. Instead of marine reptiles like mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, today’s oceans are patrolled by killer whales, dolphins, porpoises and other marine mammals.

But not all sea monsters are extinct. Sea turtles and crocodiles, the only remaining Cretaceous marine reptiles, are still around and easily recognizable. Sharks also inhabited the ancient oceans, precursors to today's larger, more ferocious eating machines known as great white sharks.

The Smithsonian has millions of fossils in its collections representing life over millions of years, including mosasaurs from different parts of the world. How do the fossils in “Sea Monsters Unearthed” fit into the broader story of life on Earth?

The fossils in the exhibition fill a large gap in the biogeography of the world. We have an idea of what life was like in Angola’s ancient ocean because these fossils provide a detailed account of the evolutionary relationships of sea monsters from the Cretaceous. Their study not only explains where mosasaurs and other ancient marine reptiles lived, how they looked and what they ate, but also helps us understand how complex geologic processes, like the shifting of tectonic plates and the opening of an ocean where there wasn’t one before, affects all life on Earth.

Does the story of life in Angola’s ancient ocean offer us any lessons for our future?

Though humans do not operate on a tectonic scale, their actions have major impacts on ocean life. Angola’s ocean is home to one of the world’s largest marine ecosystems, supplying significant amounts of food to the world. However, overfishing threatens that ecosystem and if humans continue to exploit that resource, it may take more time to recover than humans can afford.