NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

“All the Fun Action Happens in the Galleries and Learning Centers of a Museum”—Maria Marable-Bunch

For the close of African American History Month, and looking ahead to Smithsonian magazine’s Museum Day April 4, we talk with Maria Marable-Bunch about her formal and informal education and her career in museums. A widely respected educator—recipient of the Alliance of American Museums’ Award for Excellence in Practice—and an accomplished artist, Maria, as she prefers to be called, is one of three associate directors of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

:focal(1778x981:1779x982)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Maria_Marable-Bunch.png)

Thank you for giving the Smithsonian this interview. I think young people especially are interested in hearing about how people find fulfilling careers. If you will, start at the beginning: Where are you originally from, and what was it like growing up there?

Thank you, Dennis. I’m happy to be asked.

I was born in Birmingham, Alabama. Many of my family members still live there. Those who left were a part of the Great Migration to places like Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles seeking a better life.

My parents eventually moved to Pottstown, Pennsylvania, a small industrial town west of Philadelphia. But we lived in Birmingham through the summer of 1963, during the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s civil rights campaign, a very violent and turbulent time in that city. That was the summer of the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church where four young black girls were killed. Civil rights demonstrators were attacked with police dogs and fire hoses, and the children marched (and were attacked also) for the end of segregation and Jim Crow practices. The Birmingham Campaign was a model of nonviolent protest, and it caught world attention to racial segregation. That campaign led the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

It was very much a part of my growing up. My maternal grandmother lived across the street from the home of Fred Shuttlesworth. My father’s family lived a few houses away. Mr. Shuttlesworth was a civil rights activist who led the fight against segregation and racism as a minister in Birmingham. He was a cofounder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and helped to initiate the Birmingham Campaign. When Mr. Shuttlesworth was home visiting his family, he always came to see my grandparents and to update them on what was happening with the activist work of Martin Luther King, Jr. As a young child and into my pre-teen years, I often had the chance to join them on their porch to hear Mr. Shuttleworth share news about the movement and Dr. King’s plans.

How have those experiences shaped who you are today?

Hearing about and witnessing the civil rights movement, and experiencing segregation in Birmingham, impacted my worldview in many ways: That life is not always fair, but you can—and in some cases are obligated to—push for a better life and a better world. This is what my parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins, teachers, and neighbors taught me growing up as a child in Alabama.

That same viewpoint helped me a lot when my family moved to Pennsylvania. The North was supposed to be the land of no segregation, no discrimination. That’s another story of a time and place that did not live up to its reputation as an open and welcoming society for African Americans.

Do you have memories of being singled out because of your color?

Every day I am reminded that I am different because of the color of my skin. On the streets and the Metro, in stores, by neighbors, and even in the workplace.

What are some of the challenges of being black in America in 2020?

Let me give one broad answer: Having to remain vigilant to maintain freedoms and rights people fought for over 400 years. And the struggle continues.

Tell us about your education. What did you study in school?

Our parents also took my siblings and me to visit museums, historical sites, and national parks when we were children. This was my first introduction to the world of collections, history, art, and culture.

I enjoyed drawing as a child and took private art lessons throughout high school. It seemed natural to me to attend the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the University of the Arts. Both are in Philadelphia. The academy, which is part of the museum of the same name, is a school for the study of classical studio art—painting, sculpture, and printmaking. It’s the school artists like Thomas Eakins, Henry Ossawa Tanner, Mary Cassatt, Laura Wheeler Waring, and Barkley Hendricks attended.

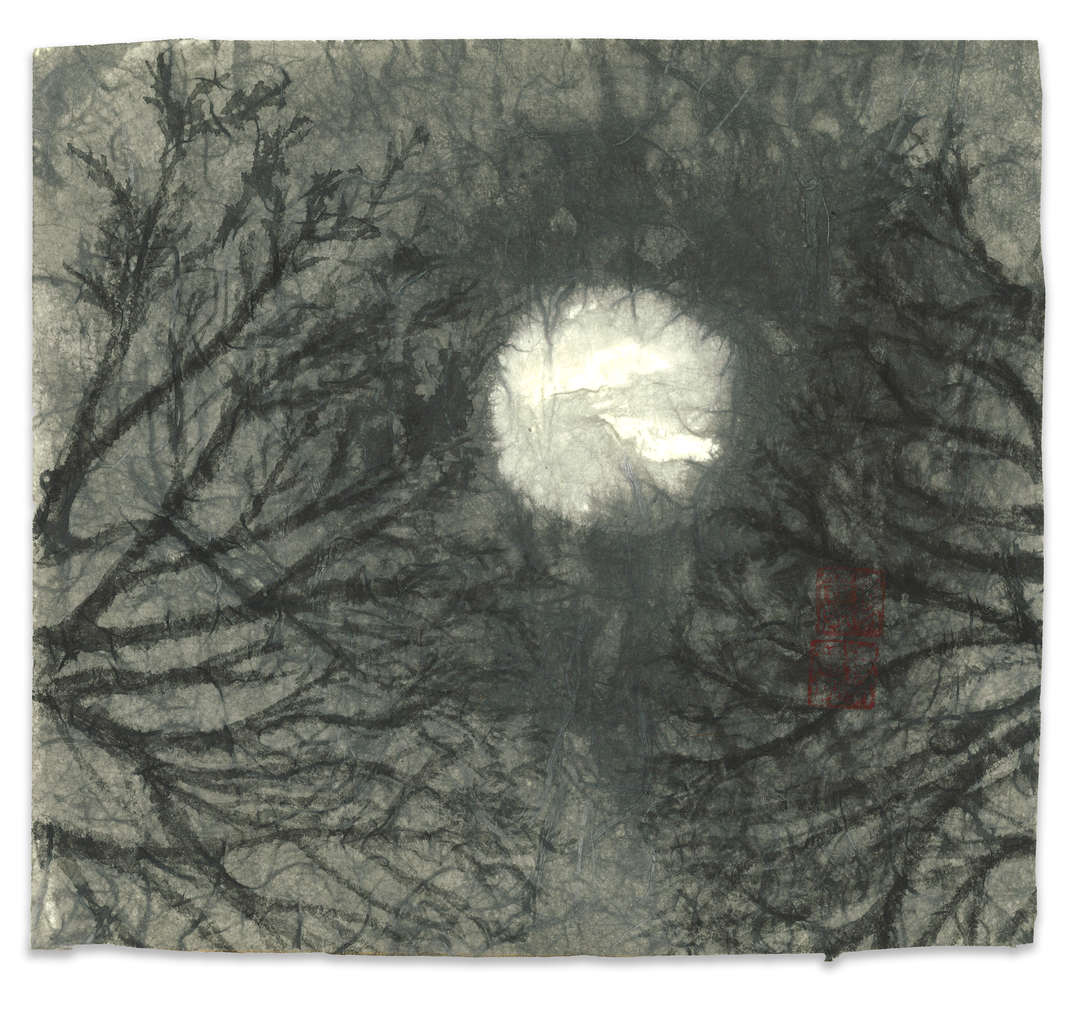

My favorite medium for painting is pastels on paper, and for printmaking, etching on copper plates. My subjects are landscapes, still life, and abstract. I also create works using Chinese brush-painting techniques.

Is art what led to your working in museums?

Yes. The museum that really launched my career was the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I interned in several of its departments, from communications to education. My work in education convinced me that that was where I most wanted to be—educating the public about the collections and sparking curiosity and wonder in children. Museums are those magical places where you can do that.

At the Philadelphia Museum of Art, I had the opportunity to work on projects like Super Sunday on the Parkway and the Mobile Art Cart. Benjamin Franklin Parkway is Philadelphia’s answer to the National Mall—one outstanding museum after another—and Super Sunday on the Parkway was a giant block party celebrating the city’s ethnic and cultural life. The Mobile Art Cart circulated in Philadelphia neighborhoods during the summer months offering art experiences for kids who might not be able to come to the museum.

I was also mentored by the most amazing group of museum educators, and they inspired me to pursue graduate school in museum education. During my graduate studies, I spent a semester interning at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. No, it’s not an art museum, but it gave me the opportunity to explore another interest of mine—flight and space exploration.

Since completing my formal education, I’ve worked at the Newark Museum, in Newark, New Jersey; the Southwest Museum, now part of the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles; Kidspace Children’s Museum, in Pasadena, California; the Smithsonian Central Office of Education; the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C.; and the Art Institute of Chicago. I’ve also worked at the US. Capitol Visitor Center and the National Archives Museum, two other places in Washington that are not usually thought of as museums, but that do offer exhibitions and visitor tours and activities.

It’s been a privilege to work in such a variety of museums—anthropologic, children’s, general history and culture, art, archival, even a historical site. The experiences I gained at each place have enabled me to build a career with a national and international reach and a focus on education.

Why are museums important?

Museums have the collections. “The stuff,” I call it. Not just art, but historic objects, photographs, archives. Bugs, frogs, mosquitoes. These things from all over the world—and beyond in the case of Air and Space—and from all periods of time make museums places to explore, use your imagination, dream, touch, smell, learn, and educate.

How did you come to join the staff of the National Museum of the American Indian?

While my work at the National Archives was fulfilling, I longed to return to working with collections of art, history, and culture. The National Museum of the American Indian offered that opportunity. I saw the position advertised on USAjobs.gov and decided to apply for it.

You’re the museum’s associate director of museum learning and programs. Education is still the work you’re most passionate about.

It is. In the early days of my career, I thought I wanted to be a museum director, but that was before I learned about museum education.

We need directors, curators, collections managers, and exhibit designers, but all the fun action happens in the galleries and learning centers of a museum. Visitor services, cultural interpretation, public programs, and education staff are the best. They bring to life all the stuff in the museum.

What is the difference between working in other museums versus working at the American Indian Museum?

The major differences are in the mission, messaging, collection, and audience. The best practices of museum education and interpretation are the same.

I’m leading a major education initiative here—Native Knowledge 360°. The museum’s goal for NK360° is to re-educate the public about Native Americans and their continued contributions to this nation—economically, socially, and in education.

Are there stereotypes you hope to break in this role?

May I give another very broad answer? Changing the narrative about Native Americans—helping people understand Native America’s history and appreciate its cultural diversity and the vibrancy of Native communities today.

Do you see challenges in working with Native communities?

Yes: Gaining communities’ trust and confidence in the work I do.

What path do you recommend for people of color who’d like to become museum professionals?

Internships are key to gaining professional experiences and skills. Networking is also key and often starts with internships, and through attending professional conferences when that’s possible. Internships and networking often lead to employment. Those are the first steps to building a career.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

I think I’ve said enough for now. Thank you for inviting me to talk about all this.

It’s been a pleasure. Thank you.

Saturday, April 4, 2020, is Museum Day, an annual celebration of boundless curiosity hosted by Smithsonian magazine. The National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., and New York City is always free, so visit us any time (except December 25). On Museum Day, take the opportunity to see participating museums and cultural institutions across the country free by presenting a Museum Day ticket. Each ticket provides free admission for two people. Some museums have limited capacity, so reserve early to have the widest choice of how to spend the day.

Where will your curiosity lead you this Museum Day? Let Smithsonian know @MuseumDay #MuseumDay #EarthOptimism.