Customized Pasta Shapes as Designed by You or Even an Architect

Coming soon to a table near you: print-on-demand pasta

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/a8/7ca81d5d-5c79-4c18-b09f-ae19aa0bbe7f/architect-pasta-2.png)

Grocery store shelves everywhere are filled with dozens of different shapes and sizes of pasta, but if Barilla has their say, penne, rotini, and farfalle will be joined by roses, fossilized dolphin skulls, and Venus de Milos (de Mili?) - or any other weird or beautiful shape you can think of for that matter. According to The Guardian, the pasta giant is exploring the use of 3D printers to create customized pasta shapes. And why not? We're already 3D printing guns, human ears, even houses. By that comparison, printed pasta seems rather pedestrian.

Though they're only in the early phases of their research, Barilla hopes to one day have the capability to print 20 pieces of pasta in two minutes. The pasta printers seem to be targeted for high-end commercial kitchens but might end up in your home too. So instead of filling your pantry with blue boxes, you can fill it with Barilla's proprietary pasta print cartridges. No word yet on 3D printed meatballs, atlthough I hear Keurig is looking to branch out into broths and sauces (really!). Welcome to the future, where all your food comes in cartridges. Bon Appetit!

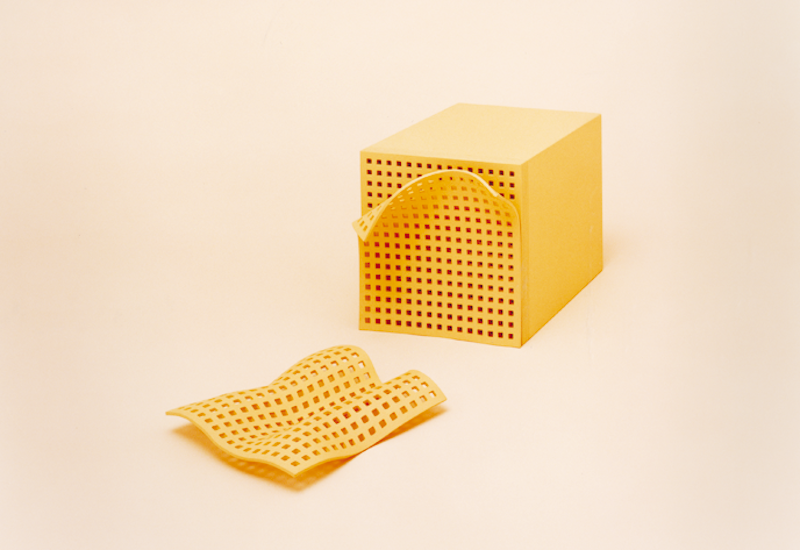

On a more optimistic note, this futuristic designer pasta reminds me of the Architects’ Macaroni Exhibition, a show curated by Muji art director Kenya Hara in 1995.

Sponsored by the Japan Institute of Architects, the Architects’ Macaroni Exhibition was an effort to showcase the talent of 20 Japanese architects in a way that can be clearly understood by the general public: macaroni design. For Hara, the show was an early and sincere effort to design food. Cooking could be considered a form of design, and even some basic foodstuffs could perhaps thought of as “designed” in its preparation. As Hara notes, “macaroni is an object has has already undergone some preparation, so because we’re just giving form to a powdered material, it doesn’t really matter what shape we give it. Therefore, the process of shaping it can be called design.” Hara wondered why, if macaroni is designed, it’s hasn’t changed . Why are there only a few traditional preparations? Why aren’t there macaroni trends? Could Kraft or Barilla come out with a new model every year (something other than novelty cartoon shapes, that is)? These are the questions Hara hoped his exhibit might answer.

While creating their designs, which were modeled at twenty times the size of an actual noodle, the architects had to address classic pasta problems like heat conduction, sauce application, and ease of production. But they were also challenged to avoid anything resembling the simple, traditional shapes we’re all familiar with. Each macaroni design was paired with a recipe created specifically to complement the noodles particular idiosyncrasies.

While the exhibition was popular, no manufacturers were enticed to commercially produce any of the macaroni shapes. This is largely because the shapes were just too idiosyncratic. Hara admits that he over-romanticized pasta design in relation to the absolute juggernaut that is the commerical pasta industry. "The various gaps between my expectations and reality included the mammoth quantity prodcued and the degree of elaboration and exactitude in planning," Hara wrote in his book Designing Design. "A design that is fairly good but not excellent will never motivate the dynamics of commercial produciton or the market." Good advice for designing anything, really. As it turns out, the traditional pasta shapes we all know and love may seem "boring" to some, but they're incredibly sophisticated designs that earned their place on your plate - at least until the Pastajet hits the market.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)