NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Get to Know the Scientist Reconstructing Past Ocean Temperatures

Meet the scientist reconstructing past ocean temperatures to solve today’s environmental problems.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Ocean_waves_crash_against_rocks..jpg)

Brian Huber has always been curious about the past. As a child finding arrowheads on his family’s farm, he’d wonder who made the arrowhead, what the landscape looked like at the time, and what the arrow’s target was. So, when a college a professor introduced him to paleontology, he was hooked.

Now a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, Dr. Huber uses fossils to discover clues about past environments and how organisms lived. As part of the Meet a SI-entist series, Huber tells us more about his “climate detective” work reconstructing past ocean temperatures, and what makes him optimistic for the future.

What do you do at the Smithsonian?

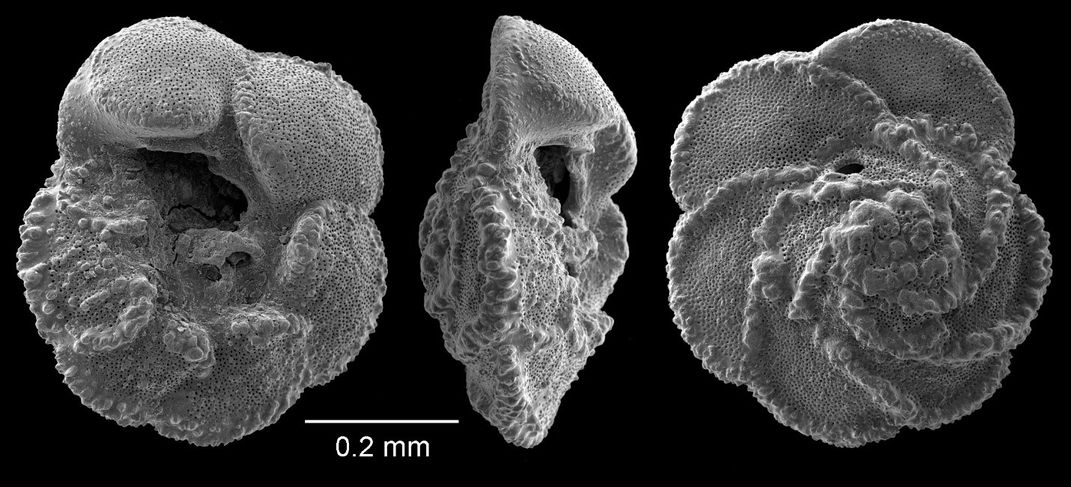

I study microscopic fossils called foraminifera, which are single-celled organisms with distinctive shells. Their fossil record goes back at least 540 million years ago to the early Cambrian period, but they still live in the ocean today. Most of my research focuses on foraminifera that lived during the Cretaceous (145–66 million years ago). I look at the evolution and extinction of different species of foraminifera and analyze the chemistry of their shells to reconstruct ocean temperatures throughout Earth’s history.

How has your work changed since COVID?

Usually, I’m busy participating in committees, mentoring interns and post-docs and involved with lots of projects—all of which take time away from research. But right now, my calendar has really cleared! Working from home has allowed me to focus on finishing up projects that have been on the back burner, like getting through a backlog of data that I haven’t had time to write up for publication. I’m currently writing a paper revising a lot of different species of foraminifera in a group that’s been poorly defined for decades. We’re naming several new species and genera.

What excites you about working at the Smithsonian?

I love the opportunity to pursue research questions using the museum’s collections and specimens I collected through my own field work. I also like helping build exhibits like the Ocean Hall and Fossil Hall and educating the public. And I really enjoy working with my colleagues, they’re a great group of very talented, enthusiastic and motivated people.

Today is World Ocean Day and the first anniversary of the opening of the National Fossil Hall. How does knowing about the ocean’s past change the way you think about its current state and its future?

The past is a framework for understanding how the natural system works today. The ocean sediment cores I’ve studied show that temperatures were very warm during the Cretaceous because of major volcanic activity that produced a lot of carbon dioxide.

CO2 is a greenhouse gas. It’s a blanket that’s kept the Earth warm for millions of years. But the rate that we are burning and releasing it into the atmosphere now is much faster than anything that’s happened before. We’ve burned 370 billion tons of CO2 since the 1850s, and half of that just since the 1970s.

We know from the past that the Earth and life are resilient. So, something will survive; the question is what. The biggest concern is how rapidly the ocean has changed, especially in the past few decades. People used to think of the ocean as too vast to be affected by what we do on land—that it would always be a reliable food source. Now, we realize that coral reefs worldwide are in peril, many fish species have been over-harvested and even accidental bycatch has caused drastic reductions among some marine life.

How do you find optimism for the future in all this adversity?

What’s amazing about humans is we seem to get ourselves out of many of the fixes that we put ourselves into. We engineer things to solve problems. The hope is that we can use technology to find a way to put the genie back in the bottle and to live lives comfortably but in a way that’s more environmentally sound.

I’m optimistic because technology and engineering keep improving the tools we use to solve questions from the past. As we learn more about the past, we better understand how Earth’s climate-ocean system worked and why some extinctions occurred, which can show us how to manage our current global environmental problems.

Another thing that gives me hope is the increasing amount of international collaboration in science. When we work together, we get multiple perspectives which helps us understand the world better. There’s a lot of exciting science going on, and the hope is that the public finds out about it and realizes how important science is in our lives—that you can’t ignore science.

What are you most proud of accomplishing so far in your career?

At a pretty early stage of my career, I found evidence for extremely warm temperatures around Antarctica during the Cretaceous. My argument was dismissed as too unlikely to have been real, but over my career, more fossil and chemical evidence have shown that there actually was a time when Antarctica was covered by forests and temperatures remained above freezing even during months of polar darkness.

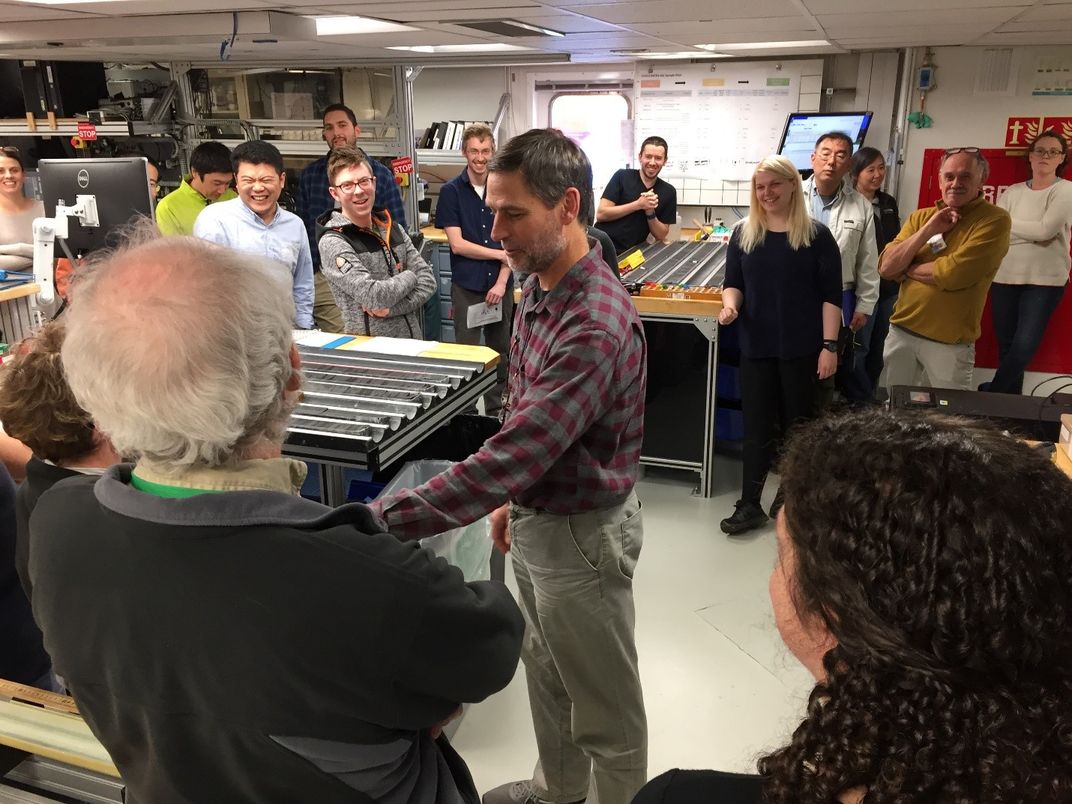

So, it’s been my quest to build out the ocean’s temperature history further and further back into the Cretaceous. Answering that question has taken me to all kinds of places, including an ocean drill ship to get sediment cores to help construct ocean temperature records. In 2017, I was Co-Chief Scientist on a two-month-long ocean drilling expedition with 30 scientists from 15 different countries, and I’m excited to continue working on deep-sea samples that will reveal previously unknown details of Earth’s past. The amount of really incredible science that has come out of that International Ocean Discovery Program is just amazing, and I have especially enjoyed the collaborations and friendships that last long after people sail together. It’s like my experience being one of the lead curators on the museum's Sant Ocean Hall—our core exhibit team still gets together once or twice a year.

What advice would you give to the next generation of scientists?

Find something that excites you. What makes you curious? Maybe you’re more analytical or you like solving puzzles, using statistics or math. Just find something you’re interested in to motivate you.

Be open to asking questions and following up. Talk to the professor after class and say, “I wasn’t sure about this, can you explain more?” or “I’ve been wondering about this, I’m really excited about this, what can I do to find out more?” These days there’s so much online, there are all kinds of ways to dive in.

Finally, getting your research out there is really important—not just publishing, but also going to meetings and interacting with people in and outside your field. One of the most gratifying things in my career has been seeing how paleontology went from a pretty narrowly focused science to one that is really collaborative. Be open to collaboration because you’re not going to solve problems by yourself, there’s a lot of different angles that these things need to be tackled from.

Meet a SI-entist: The Smithsonian is so much more than its world-renowned exhibits and artifacts. It is a hub of scientific exploration for hundreds of researchers from around the world. Once a month, we’ll introduce you to a Smithsonian Institution scientist (or SI-entist) and the fascinating work they do behind the scenes at the National Museum of Natural History.

Related stories:

Meet the Scientist Studying How Organisms Become Fossils

Get to Know the Scientist Studying Ancient Pathogens at the Smithsonian

Leading Scientists Convene to Chart 500M Years of Global Climate Change

Here's How Scientists Reconstruct Earth's Past Climates