NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

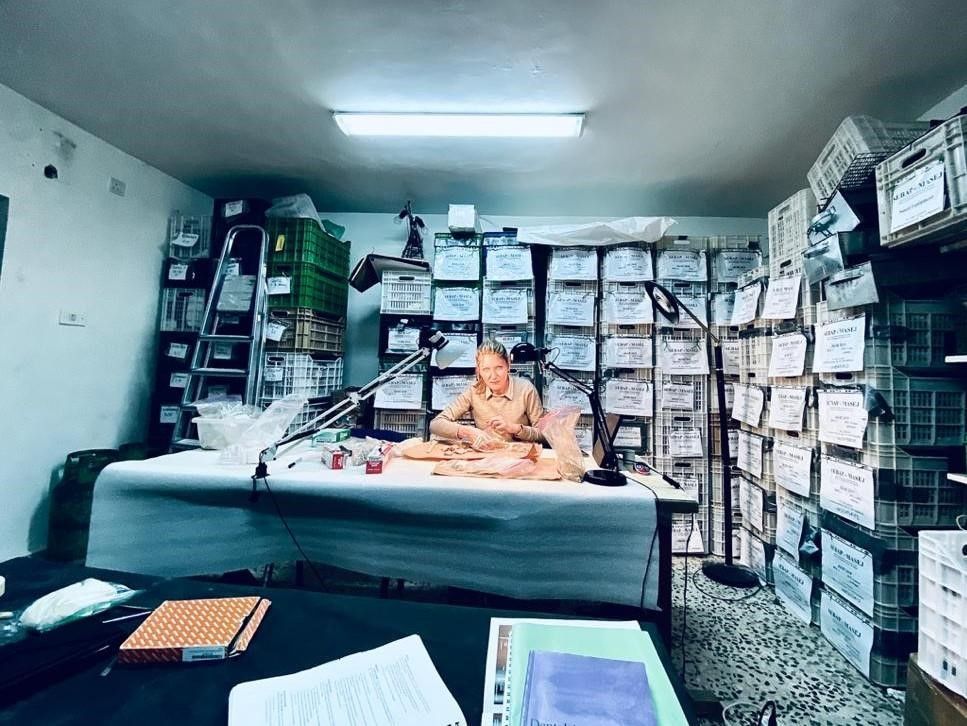

Get to Know the Scientist Studying Ancient Pathogens at the Smithsonian

Check out what an ancient pathogen expert does at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Person_Posing_for_a_Photo_with_a_Human_Skeleton_on_White_Background.jpg)

Meet a SI-entist: The Smithsonian is so much more than its world-renowned exhibits and artifacts. It is a hub of scientific exploration for hundreds of researchers from around the world. Once a month, we’ll introduce you to a Smithsonian Institution scientist (or SI-entist) and the fascinating work they do behind the scenes at the National Museum of Natural History.

When Dr. Sabrina Sholts curated the exhibition “Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World” in 2018,” she never imagined that two years later, the museum would close because of a coronavirus pandemic.

As a biological anthropologist focused on health, diseases are part of Sholts’ specialty. Sholts studies how human, animal and environmental health are connected, lately focusing on our microbiome—the communities of microorganisms that thrive on and inside our bodies – along with the pathogens that can cause illness.

Sholts tells us more about her work at the National Museum of Natural History and the “Outbreak” exhibition and gives advice to the next generation of scientists in the following interview.

Can you describe what you do as curator of biological anthropology at the museum?

I study the biological aspects of humanity – the biological molecules, structures, and interactions that are involved in being human. I’m particularly interested in health. It's fascinating how we can understand disease as an expression of how we interact with our environment — the environment being pretty much everything that's not our bodies. So from metals in our water, soil and food to microbes that are not only part of us and good for us, but also those that can be harmful.

My research can be a bit diverse, but for me, it's easy to see the themes — I'm looking at connections between human, animal and environmental health to understand how human impact on ecosystems can affect us.

What are you working on right now?

I've got a great group of students in my lab right now, Rita Austin, Andrea Eller, Audrey Lin and Anna Ragni – as well as wonderful colleagues across the museum. We're doing a few different things.

One large project that's been going on for several years is looking at indicators of health and disease in our primate collections from different human-modified environments. Andrea conceived the project, and we’re looking at how we might relate some of those conditions to changes in the microbiome.

I’m also working with Audrey and fellow curator Logan Kistler on ancient pathogen research using the museum’s vertebrate zoology collections. We’re interested in the evolutionary history of some human viruses that originate in wildlife, like the one that caused the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Some of my work is what we call bioarcheology. It’s the study of human remains in archeological contexts. I was recently in Amman with my colleagues Wael Abu Azizeh and Rémy Crassard, where I was looking at an ancient skeleton that they excavated as part of their ongoing expedition in southern Jordan. Bones and teeth can provide more information about the diet, health, and movement of people in the past.

How has your research changed since the COVID-19 pandemic?

We can’t go into the museum, we can't access specimens, we can't use our labs and we can’t go into the field. We can't do a lot of the things we've come to rely on for the research that we've been trained to do.

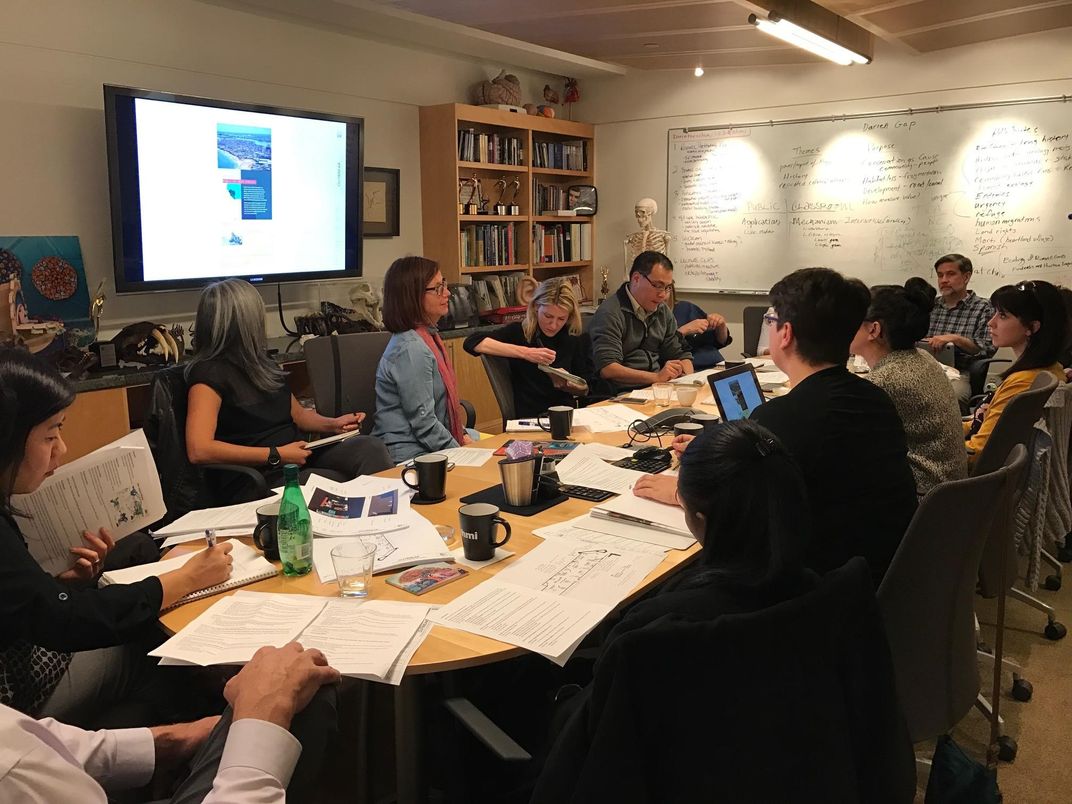

But already you see people adapting, brainstorming and really trying to work around these challenges in new ways. So we're having these virtual conversations, and thinking about how we can continue with our research in creative ways. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, I’m forming new, virtual collaborations - not just for doing science but also in communicating its role in all of this.

What excites you about working at the Smithsonian?

I've got the perfect combination of doing really exciting research, and also being able to see and experience how it can be shared. I didn't imagine when I got the job that I would become so passionate about outreach and connecting to the public through our programs and our exhibits — we can impact people in so many ways.

Do you have a favorite item in the collection or one that sticks out to you at the moment?

That's a really hard thing to ask a curator. We spend so much time researching collection items and writing papers based on our findings. Some scientists compare publishing a paper to giving birth. You can get very attached to every single one of these publications and whatever they’re about.

So we've just “birthed” another one. It’s about the cranium of a chimpanzee, which we came across in our survey of the primate collections. It's notable because there are tooth marks on it that suggest that it was chewed on by a somewhat large mammalian carnivore, maybe a leopard. Along the way, we gave it a cute name — we call it “Chimp Chomp.” The paper, literally called “A Chomped Chimp,” just came out. I have to say, seeing all the lovely photos, right now, that’s probably my favorite.

What are you most proud of accomplishing so far in your career?

I'm very proud of what we've done with the “Outbreak” exhibit. Particularly because of its “One Health” message and huge network of supporters and partners that we convened. The exhibit shows people how and why new diseases emerge and spread, and how experts work together across disciplines and countries to lower pandemic risks.

A pandemic is certainly not something that we knew would happen during the exhibit’s run. You hope an exhibit like that won’t become so relevant as it has with the COVID-19 outbreak. But I'm grateful that it’s prepared me to help the public understand what's going on right now and communicate the science of it.

What advice would you give to your younger self or to the next generation of biological anthropologists?

Appreciate the value of having someone to guide you and mentor you — someone who really cares about you. Understand its significance and carry that relationship throughout your career, if you can.

And be open-minded. Don’t be afraid to work at the intersections of where disciplines and fields traditionally divide us. Have conversations that may put you at a disadvantage in terms of what you know, or what’s familiar, but from which you can learn a lot and hear different perspectives. Embrace a broad skill set and a really diverse community of peers and partners.

Why is having a diverse community of peers important?

We need different ideas. We need to see things from every possible angle to get the most out of anything we study, learn and understand. I think that if you only interact with and listen to people who are like you, you limit the kinds of conversations you have. You’re going to miss some other valuable ways of looking at things.

Have you had any mentors or role models that helped get you where you are today? Is that something that you think about now that you’re at the top of your field?

I've had a number of really significant mentors and guides on this journey, going all the way back to even before high school. I credit them all.

When I was a student, I was operating with so much support. I had the independence to pursue something that I was interested in. That's something I try to do with my students: give them the freedom, flexibility and encouragement to really pursue their interests as they grow.

I take very seriously the privilege to be able to support such amazing young scientists and to facilitate the incredible work that they're doing and that we can do together.

Related stories:

‘One Health’ Could Prevent the Next Coronavirus Outbreak

Meet the Smithsonian’s Newest Chief Scientist

New Smithsonian Exhibit Spotlights ‘One Health’ to Reduce Pandemic Risks