NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

10 Popular Scientific Discoveries from 2019

Celebrate the new year with some of our most popular scientific discoveries from 2019.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Anna_Phillips_-_IMG_0033_resized.jpg)

This year was full of exciting research and discoveries at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. From tripling the number of known electric eels to uncovering how humans changed nature across millennia, our researchers addressed fundamental questions, sparked curiosity and showed the beauty and wonder of our planet with their research. Here are some of our most popular discoveries from 2019.

1. Humans first caused environmental change earlier than we thought

We transform our environment by building roads, airports and cities. This isn’t new. But, according to a new study published in Science, we’ve been doing it longer than we thought.

Smithsonian scientists Torben Rick and Daniel Rogers were part of a group of more than 100 archaeologists who used crowd-sourced information to discover that, by 3,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers, pastoralists and farmers had already significantly transformed the planet. This is much earlier than scientists previously thought and challenges the idea that large-scale, human-caused environmental change is a recent occurrence.

2. Scientists triple number of known electric eels

Despite human-caused environmental change, scientists continue to discover new species – renewing the charge for biodiversity conservation around the world.

In a shocking discovery reported in Nature Communications, C. David de Santana – a research associate in the museum’s division of fishes – and collaborators described two new species of electric eel in the Amazon basin. One of the eels, Electrophorus voltai, can discharge up to 860 Volts of electricity – making it the strongest known bioelectric generator. The finding reveals how much remains to be discovered in the Amazon.

3. Meteorite that killed the dinosaurs changed the oceans too

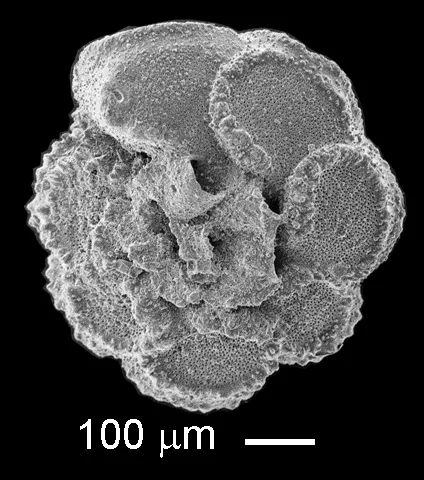

The best way to learn what the future has in store for us is to look to the past. In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Smithsonian paleontologist Brian Huber shows how the Chicxulub impact did more than kill off nonavian dinosaurs. It changed ocean chemistry.

Huber and collaborators used boron isotopes — atoms that have different numbers of neutrons but are the same element — from the shells of small single-celled organisms called foraminifera, to measure the chemical makeup of the oceans right after the impact. It turns out that the ocean rapidly acidified. The discovery helps scientists better understand the consequences of ocean acidification in a time when modern oceans acidify from increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

4. Terrestrial life thrived after dinosaurs went extinct

For many, a new year brings new life which isn’t unlike terrestrial life after the dinosaurs went extinct.

In a breakthrough discovery reported in Science, Sant Director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History Kirk Johnson and two of the museum’s paleontologists Richard Barclay and Gussie Maccracken were part of a research team that discovered how terrestrial life thrived after the nonavian dinosaurs went extinct about 66 million years ago.

The research team studied a site in Colorado where unusually complete fossils of mammals, reptiles and plants had been found. They determined that within 100,000 years after the K-Pg extinction event which killed the dinosaurs, mammal diversity doubled, and maximum body size increased to pre-extinction levels.

Why mammals grew is unclear. But the team suspects that new plants found alongside the mammals at the Colorado site may have fueled the growth. The discovery is a glimpse into the first million years after the K-Pg extinction event and shows the true tenacity of life.

5. New species of beaked whale

As conspicuous as a whale can be, sometimes they escape science’s eyes entirely.

For years, Japanese whalers suspected there might be two different kinds of Baird’s beaked whales. They weren’t wrong. In a study published in Scientific Reports, a team of researchers - including Smithsonian scientist James Mead – described a new species of beaked whale. The new species, Berardius minimus, is different from the original Berardius bardii in that it is considerably smaller, has a shorter beak and is entirely black.

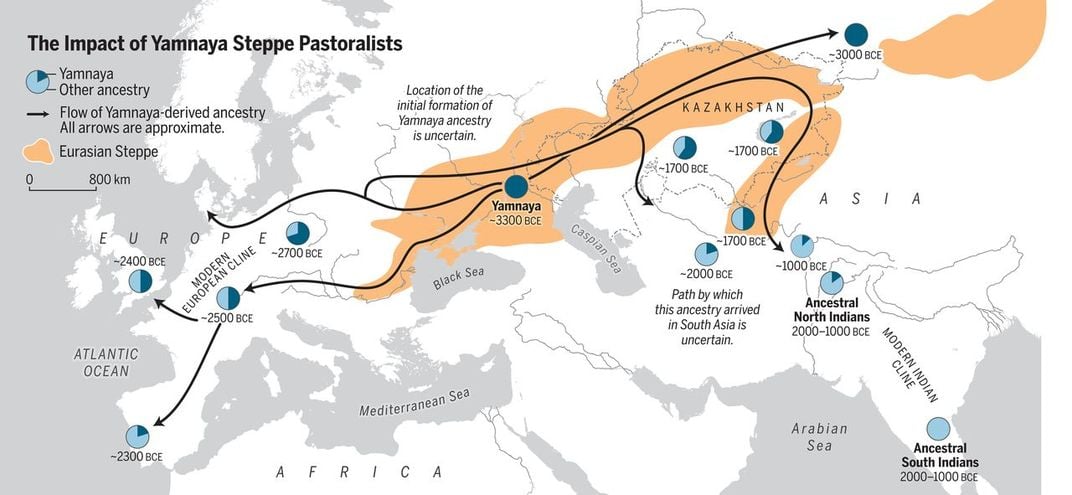

6. Humans migrated to South and Central Asia 4,000 years ago

DNA links us all together and can help us understand how human populations are related to each other.

In a new study published in Science, Smithsonian anthropologist Richard Potts and his colleagues used ancient DNA to trace modern South Asian ancestry back to early hunter-gatherers of Iran. The analysis revealed that the Eurasian Steppe population spread not only to Europe but also South and Central Asia, carrying Indo-European languages with it. The findings help scientists better understand human migration and the spread of Indo-European languages.

7. Scientists Solve Darwin’s Paradox

Charles Darwin once questioned how coral reefs could flourish in their nutrient barren waters. It was a puzzle he never figured out, eventually called Darwin’s Paradox. Now, nearly 200 years later, a team of scientists – including Smithsonian ichthyologist Carole Baldwin – may have finally put the pieces together.

In the study published in Science, Baldwin and her colleagues show that the larvae of small fishes that tend to dwell near or in the seabed — called cryptobenthic fishes — could be the previously unaccounted source of food necessary to support the great diversity of life in coral reefs.

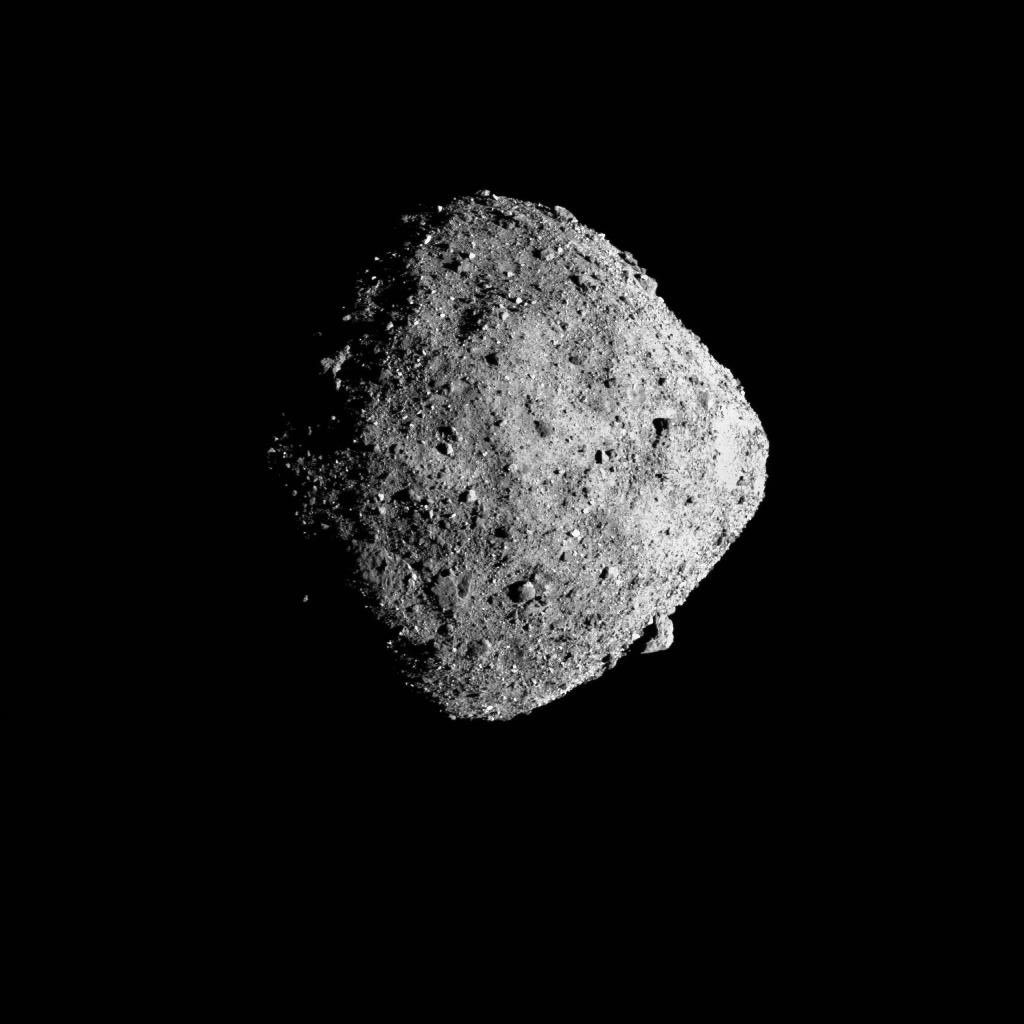

8. Asteroid sheds rocks

It looks like we’re not the only ones shedding pounds in pursuit of a new year’s resolution.

According to a study published in Science, researchers working on NASA’s OSIRIS-REx project – including Smithsonian scientist Erica Jawin – discovered that the asteroid Bennu ejects rocks from its surface into space. Why this is happening remains a mystery, but the research team thinks it could be from temperature changes causing fractures in rocks on the asteroid’s surface. In any case, the findings confirm that Bennu is an active asteroid.

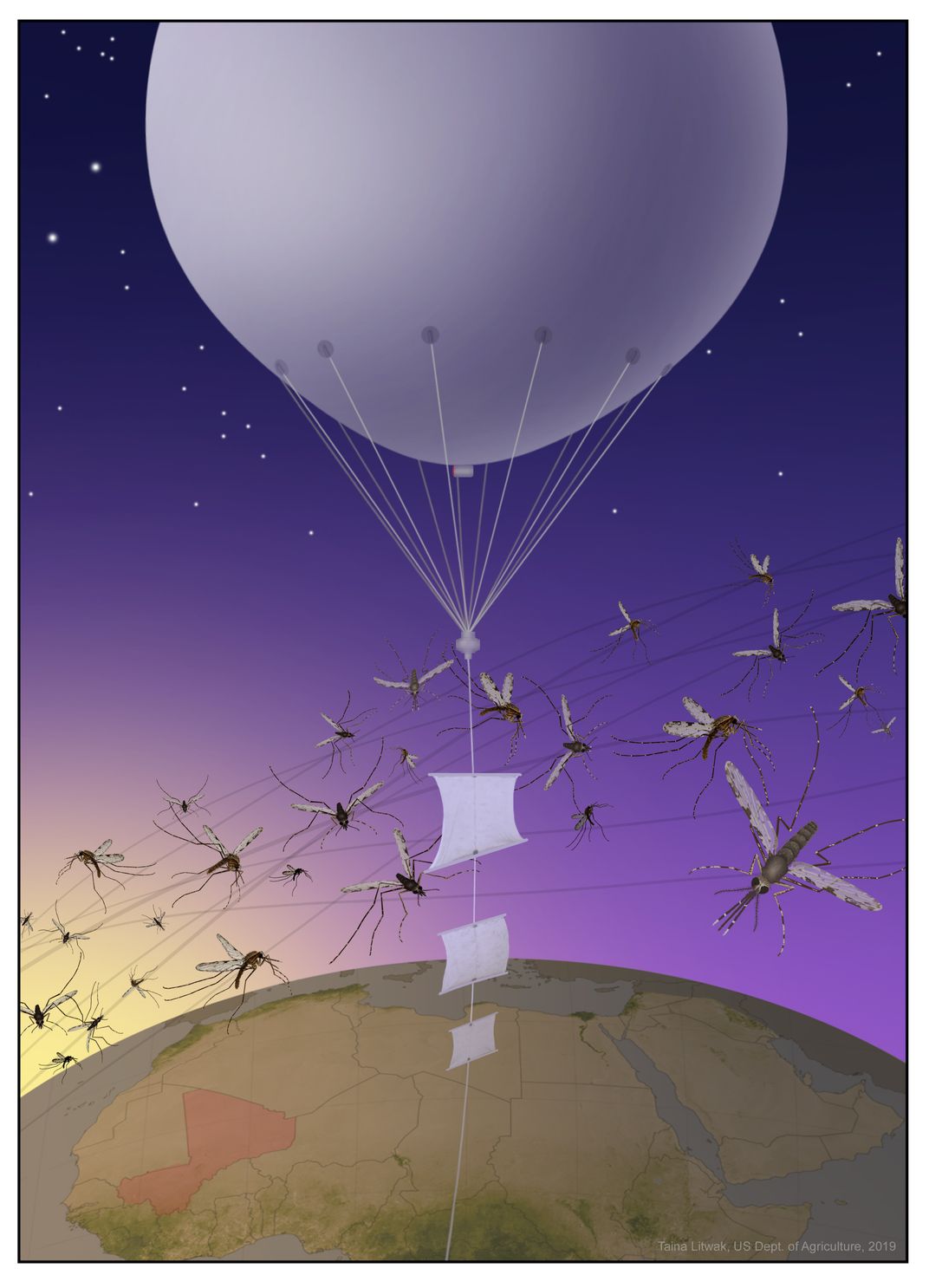

9. Malaria Mosquitos travel long distances by riding the wind

Think mosquitoes can’t be any more annoying or dangerous? Think again. According to a study published in Nature, malaria-carrying mosquitos use the wind to travel long distances and escape harsh desert conditions.

Smithsonian researchers Yvonne Linton, Lourdes Chamorro and Reed Mitchell were part of a team that analyzed thousands of mosquitos caught by hoisting sticky panels 290 meters into the air on helium balloons. They found that infected mosquitoes travelled hundreds of kilometers by riding the wind to drop themselves and their pathogens into new places. The discovery explains how malaria remains in dry environments like the Sahara Desert and could help predict and address future outbreaks of mosquito borne-diseases.

10. First North American medicinal leech described in 40 years

But not all bloodsuckers are created equally.

In a study published in the Journal of Parasitology, Anna Phillips – the Smithsonian’s curator of parasitic worms – and her team described a new species of medicinal leech found in Southern Maryland. The new leech, Macrobdella mimicus, was first thought to be a familiar species called Macrobdella decora but DNA sequencing and physical traits revealed otherwise. The discovery is the first new North American medicinal leech species described since 1975 and shows how much diversity remains to be discovered - even within 50 miles of the museum.

Related stories:

Fish Detective Solves a Shocking Case of Mistaken Identity

This Smithsonian Scientist is on a Mission to Make Leeches Less Scary

Check Out Some of Our Most Popular Discoveries from 2018

Countdown to the New Year: 7 of Our Favorite Discoveries from 2017