Tour Paris With the Marquis de Sade as Your Guide

Traces still remain in the City of Love of the famed author and sex icon

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4e/bd/4ebde427-6f0a-42a1-8a3b-dc5aba07fef2/42-60001186.jpg)

The Marquis de Sade, long reviled for his lurid erotic writings, is back in fashion. As the French continue to celebrate the 200th anniversary of his death on December 2, 1814, increasing numbers of literary pilgrims are exploring Paris for off-beat Sadist lore. Of course, this requires a little more imagination than, say, revisiting the Paris of Hemingway or Picasso. Much of pre-Revolutionary Paris vanished in the 19th century, when the city was transformed from the medieval warren of Sade's time into the open "City of Light" by the urban planner Baron Haussmann. The Sade family manse, the Hotel de Condé on the Left Bank, was demolished, and the site now lies under a busy thoroughfare near the Boulevard St. Germain.

But it is still quite possible—and extremely pleasant—to channel Sade by exploring the French capital with the eyes of an Ancien Regime aristocrat. A man of voracious appetites, the Marquis was obsessed with Gallic luxuries still sought out by travelers today: fashions, wines and gourmet foods. (He even demanded his wife bring culinary delicacies, such as plump olives, Provençal cheese, roast quail and smoked hams to his prison cell.) Today, the survivals of Sade's 18th century world include some of the most romantic and atmospheric corners of Paris -- and none of them, I hasten to add, involve secret dungeons or depraved attendants carrying whips.

The most evocative neighborhood from the era is Le Marais on the Right Bank, spreading across the 3rd and 4th arrondissements. Visitors should start at the majestic Place des Vosges. Dating from 1612, its leafy linden trees shade the gardens and gravel paths, with an array of 17th-century houses in a coherent design on every flank. On its northern side, an archway leads to the grandiose Pavillon de la Reine, the Queen's Pavilion, a luxurious hotel in a 17th century mansion whose stone courtyard walls are cascading with lush green ivy. An oasis of calm far from Paris' often chaotic traffic, it is named in honor of Anne of Austria who stayed nearby, and its contemporary rooms have maintained their historic flair, many hidden in expansive attics with four poster beds and plush velvet wallpaper. (In fact, in a contemporary version of Sade's scandals, the French politician Dominique Strauss-Kahn chose the discreet hotel as his refuge in Paris after his escape from New York, where he was charged with sexually assaulting a maid in 2011.) The splendid Pavilion is a tourist attraction in itself, and those who cannot afford its pricey rooms can enjoy a meal or coffee in the courtyard, imagining the clatter of horse's hooves on the cobblestones.

To descend deeper into Sadistic lore, stroll a few minutes away to the Marais' most decadent hotel, located in the former presbytery of a renovated Gothic church, the Saint-Merry. The rooms still have the raw stone walls that housed medieval monks, with windows opening over the rooftops of the district, where you half expect to see Quasimodo swinging from tower to tower. Even the antique furnishings feel heavy and brooding. On my visit, my bed was surmounted by a carved wooden gargoyle, and every morning, I awoke to church bells in a belfry only 20 feet from my head. Sade, whose literary imagination was fired by religious imagery -- depraved priests and nuns being a staple in his novels -- would certainly have approved.

The surrounding area, a poetic maze of crooked alleys and grandiose mansions, remains very much the same as it did in the 1760s, when Sade was a handsome, blonde-haired young aristocrat in his 20s frequenting theaters, literary cafes and bordellos. He also enjoyed a long stint of freedom in Paris during the tumultuous Revolutionary era of the 1790s, when he was the notorious middle-aged author of scabrous novels such as Justine and Juliette, and trying in vain to find success as a playwright. Sade penned a string of surprisingly staid social dramas before he fell afoul of Napoleon in 1801 and was banished to a mental asylum (the subject of the films Marat/Sade and Quills).

The electric atmosphere of that era can still be captured by entering one of Le Marais's most splendid mansions, which now houses the Musée Carnavalet, dedicated to the history of Paris. Often neglected by travelers in favor of the more famous Louvre and Orsay, it is one of the most compelling museums in France. Its exhibits on the Revolution contain thrilling, intimate artifacts of historical celebrities: Marie Antoinette's tiny slippers, for example, and Napoleon's favorite toiletry case. There are historic models of the guillotine from the time of the Terror, and Robespierre's attaché case, in which he carried decrees of execution to the dreaded Committee of Public Safety. (Sade himself narrowly escaped the "the kiss of the guillotine"). And the Sade connection is most vivid in a model of the Bastille, carved by an artist from one of its original stone blocks. (The hated royal prison, where Sade spent five years from 1784 and wrote 120 Days of Sodom and the first draft of his most notorious opus, Justine, was destroyed after the Revolution and now exists only in name).

Even quirkier is the Musée de la Nature et la Chasse, the Museum of Nature and Hunting, which is devoted to the aristocratic culture of hunting in France back to the early Middle Ages. Located in an antique hunting club, it is far more creative than the theme might suggest: its inventive room installations using stuffed animals, relics and haunting soundtracks, are modern works of art in themselves.

The Marquis de Sade had refined culinary tastes, and during his lifetime Parisians were experimenting with a brand new institution, le restaurant. These early incarnations vied with one another in opulent décor, and offered their patrons menus the size of newspapers, with dozens of dishes to choose from, as well as daily specials noted in the margins. There is no sure record, but it is almost certain that Sade would have visited the oldest continuously operating kitchen in Paris, Le Grand Véfour (at the time called the Cafe de Chartres), and today it remains a marvelous experience. To find it, head beneath the vaulted arches of the Palais Royal, which in the 1780s was the heart and soul of Paris, a rowdy entertainment center filled with circus acts and brothels.

Admittedly, the Palais Royal doesn’t exactly teem with iniquity today – it’s an elegant, pebble-covered park, lined with antique stores rather than houses of assignation. But tucked away in a corner, Le Grand Véfour is a theatrical gem of period opulence, with velvet banquettes, glittering mirrors and ravishing Pompeiian-style murals. One of the most expensive restaurants in Paris by night, it also offers a 96 Euro ($111) fixed price lunch menu that, while not exactly a steal, offers an immersion in a great French institution.

From here, it's a short stroll to the Boutique Maïlle on the Place Madelaine, whose famous Dijon mustards have been on offer since 1757. (Thomas Jefferson was even a patron when in Paris.) Today, Parisians flock here to sample the mustards, which come in dozens of flavors from chardonnay to roquefort, and are still sold in the same charming faience tubs as in the 18th century. Not far away is the oldest pâtisserie of Paris, Stohrer, whose 1730 store is a irresistible palace of sweets, with original lead mirrors reflecting a multi-colored array of pastries and glazed fruits. Stohrer no longer specializes in “edible art” as was the fashion in Sade’s day – intricate table sculptures of Egyptian vases, Greek temples or garden scenes made entirely from spun sugar – but one can savor the luscious baba au rhum, rum baba, invented on these premises two centuries ago.

Cross the Seine, preferably via the Pont Neuf, which was once teeming with vendors hawking fruits and meat. Today, the Left Bank has several ancient establishments frequented by Sade's contemporaries, starting with the venerable Café Le Procope, the haunt of revolutionary figures including Danton and Marat, as well as Voltaire and Ben Franklin in their day. Today, Le Procope is a slightly touristy shrine to the Revolution, with the symbol of Liberty, the red Phrygian cap, on the menu cover and bathrooms marked Citoyens and Citoyennes. But the rabbit warren of sumptuous dining salons are a delight to explore, decorated with artifacts including a two centuries-old copy of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and a preserved dinner check from 1811.

From here, true Sade devotees might detour to the Rue Mouffetard, one of the oldest streets in Paris, where the young aristocrat kept one of his several apartments for secret trysts after his marriage. Today, the street is a charming cafe-lined pedestrian mall, but it was the scene of Sade's first scandal in 1763, when the 23-year-old lured a young woman named Jeanne Testard to his rooms and kept her overnight for his bizarre erotic fantasies that were spiced with sacrilege. (Police records discovered in the 20th century reveal that he stomped on a Crucifix and screamed blasphemies while abusing himself with a cat-o'-nine-tails.) The denunciation by Mademoiselle Testard resulted in his first prison spell in Vincennes of 15 days, although Sade’s rich family was able to procure his release.

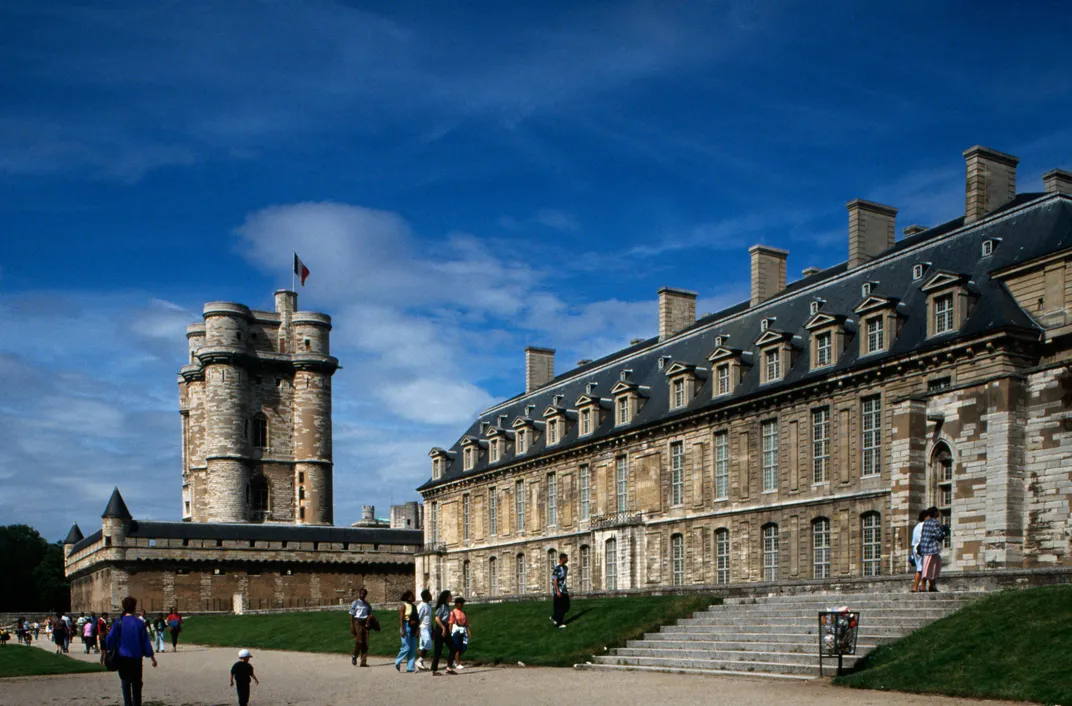

This would not be Sade's last term in the 12th century Château de Vincennes, which can still be visited on the the outskirts of the city. Now an imposing tourist attraction, it looms at the end of Metro Line 1, and tour guides proudly show off cell number six, where Sade spent seven years, starting in 1777. (Indeed, he was even referred to by wardens as "Monsieur le Six.") Although the cell is bare and chilly today, the aristocratic Sade was allowed to warm its stone walls and floor with colorful Turkish carpets, his own furniture and personal 600-volume library.

But the most picturesque Sade excursion requires several days. The Marquis' ancestral home in Provence, where he often took refuge from the authorities in Paris, was purchased in 2001 by the French fashion icon Pierre Cardin and is open to visitors. Once a difficult journey of over a week by carriage, the TGV high-speed train now runs to Avignon in 2 hours and 40 minutes; from there, hire a car and drive about 30 miles east to the small village of Lacoste. It's a classic Provençal hamlet, except that it happens to be crowned by the Chateau Sade.

Lacoste has long been popular with artists, and here one now finds the world's only memorial to Sade, a bronze statue with the writer's head in a cage, symbolizing his long years of imprisonment and censorship. When Cardin erected it, locals were worried the village would become some sort of Sade Mecca. ("At first, we thought it would bring in the bondage crowd," one artist who has lived here for decades confessed to me. "What if the village became a pilgrimage spot for weirdos? Luckily that hasn’t happened.")

The visit to the chateau itself provides an intimate view of Sade living out his fantasy of being a feudal seigneur in medieval style. For 7 Euros ($10) it is possible to explore the chambers filled with antiques and artworks. (The chateau was pillaged in the Revolution, but Cardin renovated and re-furnished it from local stores). One wall of the Marquis' bedroom remains, with sweeping views of the verdant Provencal vineyards.

In one of the strange echos of history, Pierre Cardin has started a theater festival in Lacoste, held every July in Sade's honor. The glamorous events take place under the stars in a purpose-built amphitheater. Sade himself spent much of his time staging his own work, and even organized a theater troupe to tour Provence by carriage. His fond hope to be recognized as a playwright was a goal that would forever elude him. Instead, he will always be remembered for his scabrous erotic novels, which he published anonymously and of which he would often deny authorship, dreaming of higher literary goals.

Today, as Sade's rehabilitation becomes complete, the Festival of Lacoste would perhaps be the event he would have been most tickled to attend.

_______________________________________________

Le Grand Véfour – 17, rue de Beajolais, 33-1-42-96-56-27. www.grand-vefour.com

Au Rocher de Cancal – 78, rue Montorgueil, 33-1-42-33-53-15, www.aurocherdecancale.fr

Le Procope – 13, rue de l’Ancienne Comédie, www.procope.com

Lapérouse, 51, Quai des Grands-Augustins, 33-1-43-26-68-04, www.laperouse.fr

Mustards: Maïlle, 8, Place de la Madeleine, 33-1-40-15-06-00, www.maille.us

Chocolates: Debauve et Gallais, 30, rue des Saints-Pères, 33-1-45-48-54-67, www.debauve-et-gallais.com

Pâtisserie: Stohrer, 51, rue Montorgueil, 33-1-42-33-38-20 – www.stohrer.fr

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)