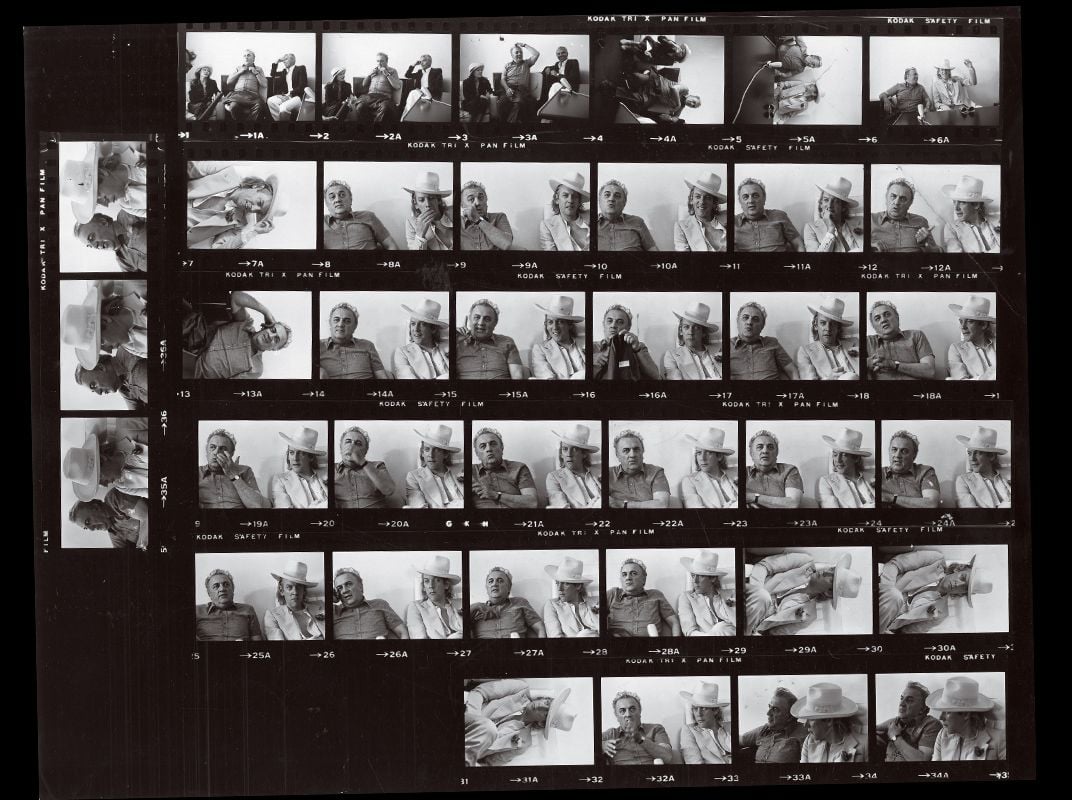

Donald Sutherland on Fellini, Near-Death and the Haunting Allure of Venice

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/e1/cfe1ab6c-b49a-438e-9144-c3654b374989/sqj_1510_venice_sutherland_01-for-web.jpg)

Editor's Note: Donald Sutherland made two films in Venice, the 1973 thriller Don’t Look Now and The Italian Job in 2003. He also played the Venetian adventurer and lover Casanova in a film of the same name by Federico Fellini. In this essay, Sutherland remembers a city that by turns terrified and delighted him.

As I sit here, wondering about Venice, a photo of John Bridger, the fellow I played in The Italian Job, crosses the screen in front of me and stops for a couple of seconds. He’s leaning into a cell phone as he walks across a damp St. Mark’s Square towards the Grand Canal, talking to an imaginary daughter just waking up in California. He’s a day away from dying in a fusillade of lead. If he’d taken a second to look up to his left, I’m sure he would’ve stopped, would’ve sensed a connection, a genetic connection, with another fellow nearly 300 years his senior, the prisoner Giacomo Casanova scrambling across Fellini’s lead-plated roof. Casanova’d just escaped through that lead roof from the dreaded i Piombi, the cells the doge had purpose-built at the other end of il Ponte dei Sospiri, Byron’s Bridge of Sighs.

Standing there in the thrall of Casanova, Bridger might have felt a passing zephyr lift up the edge of his coat. That gentle breeze would’ve been the ghost of John Baxter scurrying across that square, heading towards a small canal, a mosaic-encrusted basilica, a hooded child cloaked in one of those ubiquitous red raincoats that still confront me every time I turn a Venetian corner. I walk those streets. Cross echoing canals. I hear Prufrock remembering the lonely sound of voices dying with a dying fall. Every few steps I slow and turn around. I have to look over my shoulder. Someone always seems to be following me in Venice. They aren’t there, but I feel them. I am on tenterhooks in the city, bristling with excitement. I am very alive.

In ’68 I was not. Not really. I’d come across the Adriatic to look at the city, Mary McCarthy’s Venice Observed in hand, and in minutes I’d turned tail and run. The city’d terrified me. It’s only because I managed to muster all my strength in ’73, only because I was able to pull myself together and overcome my terror, that those three fellows are related, that their genetic connection exists.

Venice is interlinked in my mind with bacterial meningitis. In ’68 I’d picked up the pneumococcus bacterium in the Danube and for a few seconds it killed me. Standing behind my right shoulder, I’d watched my comatose body slide peacefully down a blue tunnel. That same blue tunnel the near dead always talk about. Such a tempting journey. So serene. No barking Cerberus to wake me. Everything was going to be all right. And then, just as I was seconds away from succumbing to the seductions of that matte white light glowing purely at what appeared to be the bottom of it, some primal force fiercely grabbed my feet and compelled them to dig my heels in. The downward journey slowed and stopped. I’d been on my way to being dead when some memory of the desperate rigor I’d applied to survive all my childhood illnesses pulled me back. Forced me to live. I was alive. I’d come out of the coma. Sick as a dog, but alive.

If you’re ever with someone in a coma: Talk to them. Sing to them. They can hear you. And they’ll remember. I’d heard everything they’d said in the room. I’ve not forgotten a word.

For its own purposes, MGM’d built a six-week hiatus into my Kelly’s Heroes contract so, with Brian Hutton refusing to recast me, the studio took advantage of that break and sent me to Charing Cross Hospital in England in an effort to get me to recover. It takes more than six weeks. They’d had none of the necessary antibiotic drugs in Yugoslavia. The ambulance ran out of gas on its way to the airport. They’d done seven spinal taps. The first one had slipped out of the nurse’s hand and shattered on the hospital’s marble floor. People would come into this very white room I was bedded in in Novi Sad, look at me and start to cry. Nancy O’Connor, Carroll’s wife, turned and ran, weeping. It was not encouraging. I was in lousy shape.

They erased all that in Charing Cross. Intravenous drugs. A lovely bed. Squeaky-shoed nurses. The expert woman in the basement who read the printout of the brain waves coming from electroencephalograph wires they’d attached to my head looked like the ghost of Virginia Woolf and she laughed out loud reading the patterns in front of her. She’d look up, nod at me and say “Sorry,” then look at it again and laugh some more. I had no idea what she was laughing at and I was afraid to ask.

As soon as the six weeks were up they pulled me out of the hospital, brought me back to Yugoslavia, and stood me up in front of the camera. I’d recovered. Sort of. I could walk and talk, but my brains were truly fried. The infected layers of my meninges had squeezed them so tightly that they no longer functioned in a familiar way. I was afraid to sleep. I wept a lot. I was scared of heights. Of water. The Venice I’d planned to visit, therefore, would be anathema to me. But the Turners in the Tate kept running around in my head, so I took a train and went around the top of the Adriatic to Mestre. Got on a vaporetto to the city. Looked. Took some tentative steps. And immediately turned tail and ran away. Terrified. Truly petrified. Didn’t even look back. Desperate to get my feet securely onto dry land.

So when five years later Nic Roeg called and asked me to play John Baxter in his film of du Maurier’s short story “Don’t Look Now,” I gave him a conditional yes. First, though, I told him, before anything, Francine and I had to go to Venice to see if I could survive the city. We went. Flew in. Landed at Marco Polo. Took a motoscafo to the hotel. Stayed in the Bauer Grunwald on the Grand Canal. Beautiful everything was. The city’s dampness seeped into me. Became me. It can be a truly insidious place, Venice. Unnerving. It can tell the future. Its past haunts you. Coincidences abound. Jung says coincidences are not accidents. They’re there for a reason. Venice is overflowing with reasons. The room we were staying in would be the same room that Julie Christie and Nic Roeg and Tony Richmond and I would do Don’t Look Now’s love scene in half a year later. The same room we were staying in when John Bridger happily walked across St. Mark’s Square en route to the Dolomites and death.

But it was wonderful. The city. Blissful. I love its slow dying more than most living. I had a dog with me when we filmed Don’t Look Now. A great big Scottish Otterhound. Not terribly bright but belovèd. He went everywhere with us. Years and years later, when we were there for the festival, we walked into Harry’s Bar and the bartender looked up, saw me, and with immense gusto said: “Donaldino, avete ancora il cane?” Did I still have the dog? No. I no longer had the dog. But I was home. Bellini in hand. I was happily at home.

We went looking to buy a place in Dorsoduro. Near the sestiere San Marco. We wanted to live here. Wow. Talk about rising damp. This was awesome. And very expensive. Very. We decided to rent for a while and take our time. The apartment we’d lived in when we were shooting Don’t Look Now was across the Grand Canal in Dorsoduro. In Giudecca. To get there each night the motoscafo that was assigned to me would take me to the island and stop at the too narrow canal that went inland past our apartment. Waiting there for me would be a gondola. It was another life. Completely.

Fellini’s Venice was in Rome. In Cinecittà. The rippling waters of the Grand Canal were shining sheets of black plastic. And this, too, was another life. Completely. Try sculling a gondola over a plastic sea.

Fellini came to Parma where we were shooting 1900 and confirmed we would do the picture. I drove him to Milan. He saw the complete volumes of Casanova’s diaries on the back seat of the car and one by one threw them out of the window. All of them. This was going to be his film. Not Giacomo’s. We stayed together that night in Milan. Walked the streets, two wraiths, him in his black fedora and his long black coat confiding to me that he was supposed to be in Rome. Went to il Duomo. Sat through 20 minutes of The Exorcist. Walked into La Scala, him warning me that they wanted him to direct an opera and he was not going to do one. I remember three guarded doors in the atrium as we walked in. At the desk the concierge, without looking up when Fellini’d asked to see the head of the theater, demanded perfunctorily who wanted to see him. Fellini leaned down and whispered, truly whispered, “Fellini.” The three doors burst open.

With that word the room was full of dancing laughing joyous people and in the middle of this swirling arm clasped merry go round Fellini said to the director, “Of course, you know Sutherland.” The director looked at me stunned and then jubilantly exclaimed, “Graham Sutherland,” and embraced me. The painter Graham Sutherland was not yet dead, but nearly. I suppose the only other choice was Joan.

I was just happy to be with him. I loved him. Adored him. The only direction he gave me was with his thumb and forefinger, closing them to tell me to shut my gaping North American mouth. He’d often be without text so he’d have me count; uno due tre quattro with the instruction to fill them with love or hate or disdain or whatever he wanted from Casanova. He’d direct scenes I wasn’t in sitting on my knee. He’d come up to my dressing room and say he had a new scene and show me two pages of text and I’d say OK, when, and he’d say now, and we’d do it. I have no idea how I knew the words, but I did. I’d look at the page and know them. He didn’t look at rushes, Federico, the film of the previous day’s work. Ruggero Mastroianni, his brilliant editor, Marcello’s brother, did. Fellini said looking at them two-dimensionalized the three-dimensional fantasy that populated his head. Things were in constant flux. We flew. It was a dream. Sitting beside me one night he said that when he had looked at the final cut he had come away believing that it was his best picture. The Italian version is really terrific.

There’s so very much more to say. If you’re going to Venice, get a copy of Mary McCarthy to delight you. And take a boat to Peggy Guggenheim. There were wonderful pictures there. And I don’t know about now, but certainly then, Osteria alle Testiere, Ristorante Riviera and Mara Martin’s Osteria da Fiore were wonderful places to eat. And Cipriani’s always. Dear heavens, I love my memories of that city. Even with a pair of Wellingtons ankle deep in Piazza San Marco.

Put it at the top of your bucket list. The very top.

Read more from the Venice Issue of the Smithsonian Journeys Travel Quarterly.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1510_Venice_Contrib_01.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1510_Venice_Contrib_01.jpg)