Colombia Dispatch 8: The Tagua Industry

Sometimes called “vegetable ivory,” tagua is a white nut that grows in Colombia that is making a comeback as a commodity worth harvesting

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/tagueria_631.jpg)

During World War I and World War II, some of the buttons on U.S. military uniforms were carved out of tagua, a durable white nut about the size of a golf ball that grows on a South American palm tree. The material was cheaper than ceramic or metal, so exporting tagua became a major industry in Colombia and Ecuador beginning around 1900. By the second half of the 20th century, demand halted with the popularization of plastic. Today the material is mostly forgotten in the United States.

But tagua is making a comeback, this time as a decorative novelty. While Ecuador now has a burgeoning tagua trade, Colombia's resources are only starting to be retapped. In Bogota, I visited La Tagueria, a factory in the city's gritty industrial zone. Forty employees process about 10 tons of tagua annually into colorful, intricately carved jewelry and decorations.

Tagua, sometimes called "vegetable ivory," is "the only plant product that produces a material this white, durable and pure," says factory owner Alain Misrachi.

Today tagua is more expensive than plastic, but Misrachi says it is a valuable alternative crop that helps preserve the region's tropical forests. The palm grows in the wild at lower elevations across Colombia, so there is no need to start tagua plantations. Locals collect fruit from the forest floor year-round after it falls from the tree, and the seeds are then extracted and dried.

Misrachi travels to remote regions of Colombia where native tagua grows in dense patches to speak with locals about harvesting the resource. Most remember the collecting process from stories told by their grandparents, who lived during tagua's heyday in the early 20th century. Today, radio ads produced by a La Tagueria buyer in the southern Pacific coast announce prices per kilogram for tagua. Locals bring the crop to him, and he them ships them to Bogota.

Misrachi hopes that tagua will become an alternative to more common environmentally destructive plantations, including illegal crops like coca. "Tagua palms are disappearing," he says. "We tell them not to cut down these palms, they are valuable."

Misrachi started working in his uncle's synthetic button factory in 1977, but soon became interested in tagua as an alternative. In the mid 1980s they started manufacturing buttons from Ecuadorian tagua and in 2000 he rediscovered Colombian sources of tagua and soon began branching to make jewelry other products. The Tagueria has enjoyed a lot of success, and now exports to Europe, the United States, Japan and Australia.

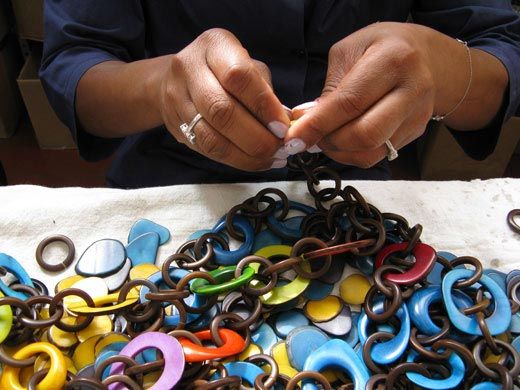

I went on a factory tour with Misrachi's son, Dylan, to learn the whole process from nut to necklace. Workers dump bags of nuts fresh from the jungle into tumblers with sand and water that strips the nuts brown skin and leaves them a gleaming white. The work is then mostly done by hand, as employees slice the nuts with band saws, tint them in simmering pots of colorful dye and assemble the pieces into myriad shapes, sizes and colors. The end result is a great variety of buttons, necklaces, bracelets and frames.

Dylan showed me photos from a recent trip he took to Ecuador, where tagua palms are always left standing in the middle of cattle pasture and locals fill warehouses with nuts awaiting export. The Misrachi family hopes that Colombia can take a similar role in the tagua trade. "It's important to be conscious of this natural product with it's own value," Alain Misrachi says. "With our work we hope to preserve this palm so the people will take care of it and create local crafts."