For Tiffany Chung, Finding Vietnam’s Forgotten Stories Began as a Personal Quest

To map the post-war exodus, the artist turned to interviews and deep research, starting with her own father’s past

:focal(1354x867:1355x868)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d3/55/d355d0cf-010d-4bb8-ba6d-1370319a2045/tiffany-chung_courtesy-of-tiffany-chung-and-tyler-rollins-fine-art-new-york.jpg)

Tiffany Chung’s innovative exploration into the untold history of the South Vietnamese since the war begins with her own story.

While her past work explored migration conflict and shifting geography in the wake of political and natural upheavals, “Tiffany Chung: Vietnam, Past is Prologue,” her first major solo museum exhibition in the United States, currently at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, begins by looking deep into the story of her own father.

He was a helicopter pilot for an elite flying team in the South Vietnamese Air Force who was taken prisoner in 1971, and spent 14 years in a North Vietnamese prison camp until the end of the war. Chung’s family then immigrated to the United States, where the full details of his war-time experience remained a mystery, especially to her.

“We begin our search of a historical memory with a personal quest. That is my case,” Chung says.

“Sixteen years ago, when I first attempted to trace my father’s wartime journey, I encapsulated my experience of crossing from Vietnam to Laos.” She took notes, mixed in with childhood memories and imagined his life in prison as she recalled her mother waiting for his return.

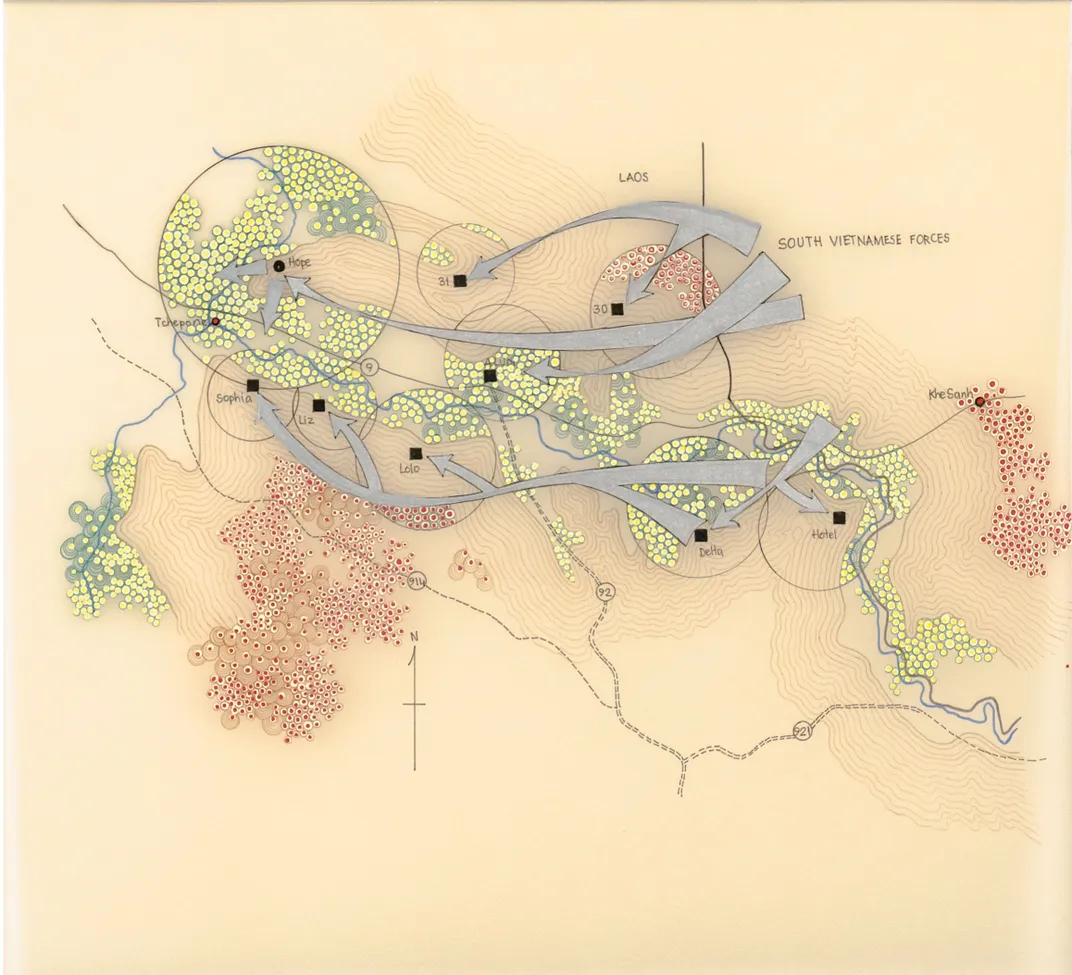

“Twelve years later, in 2015, I came across a photograph which prompted me to embark on another journey, this time to physically map the airfields that my father had frequented as a helicopter pilot. This lead to my learning and remapping of several historical events that were crucial in understanding the politics of the war in Vietnam between 1955 and 1975.”

In a poem she wrote in 2015, she tells of her observations at an abandoned airfield in Quan Loi. “It’s just another red dirt road,” she writes. “It took him 10 minutes to fly his helicopter between Quan Loi and Loc Ninh airfields. It took me 45 minutes in a Toyota 4Runner.”

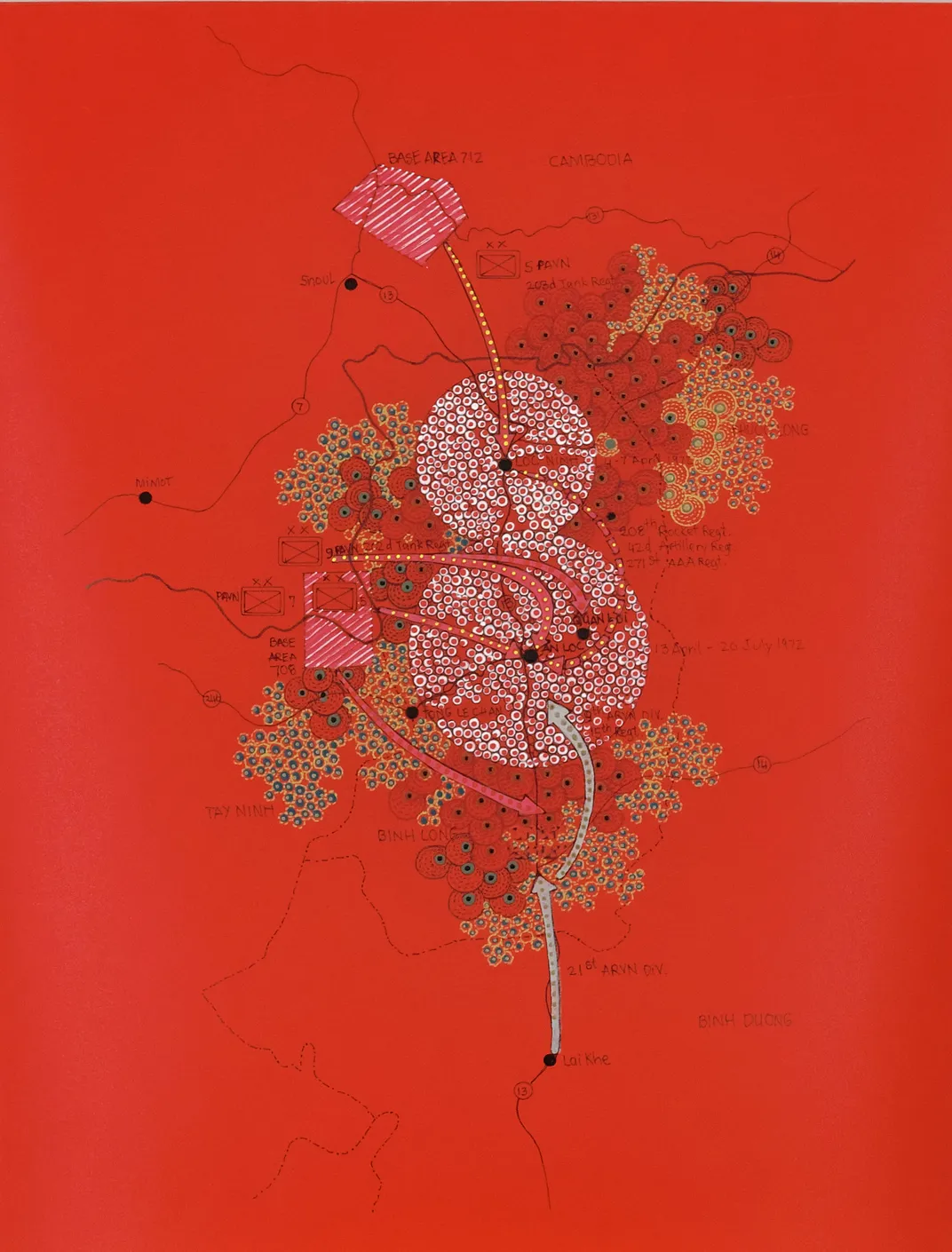

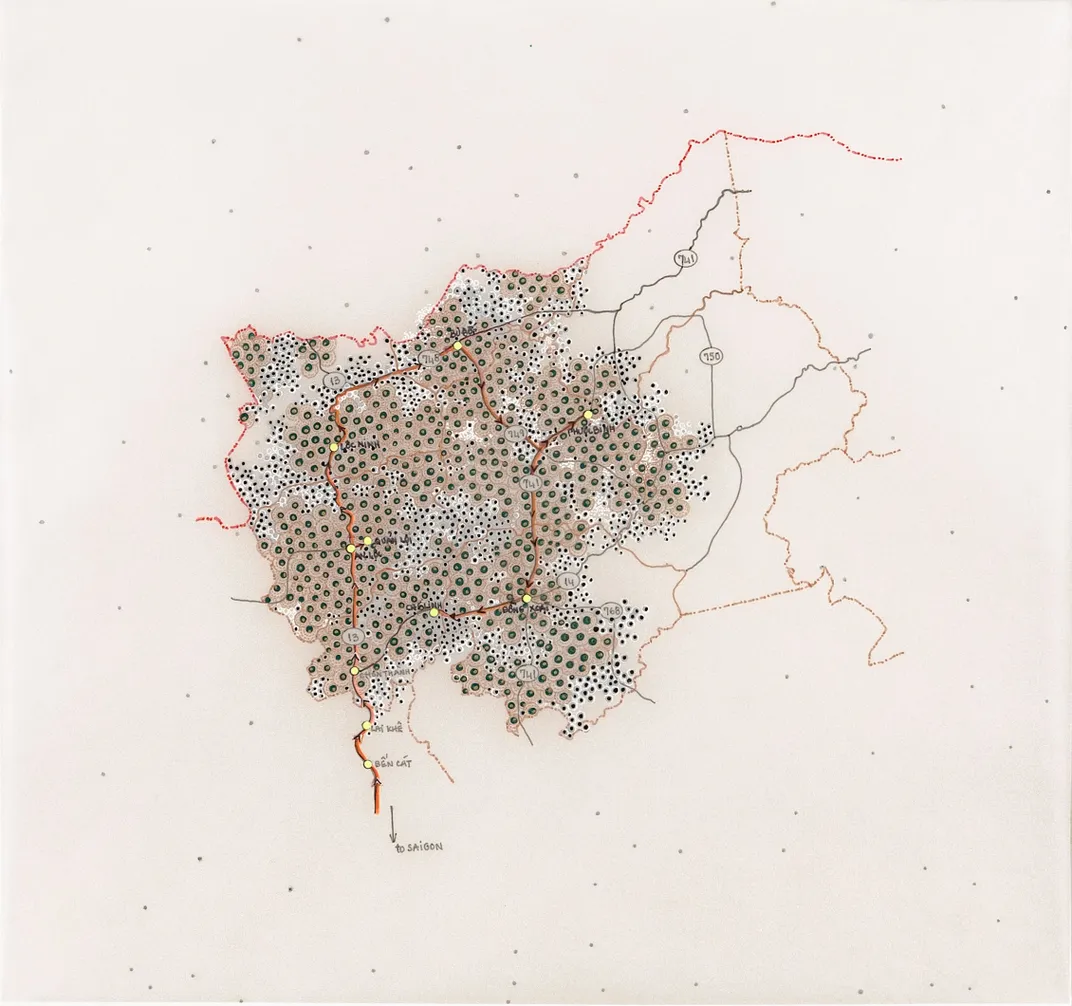

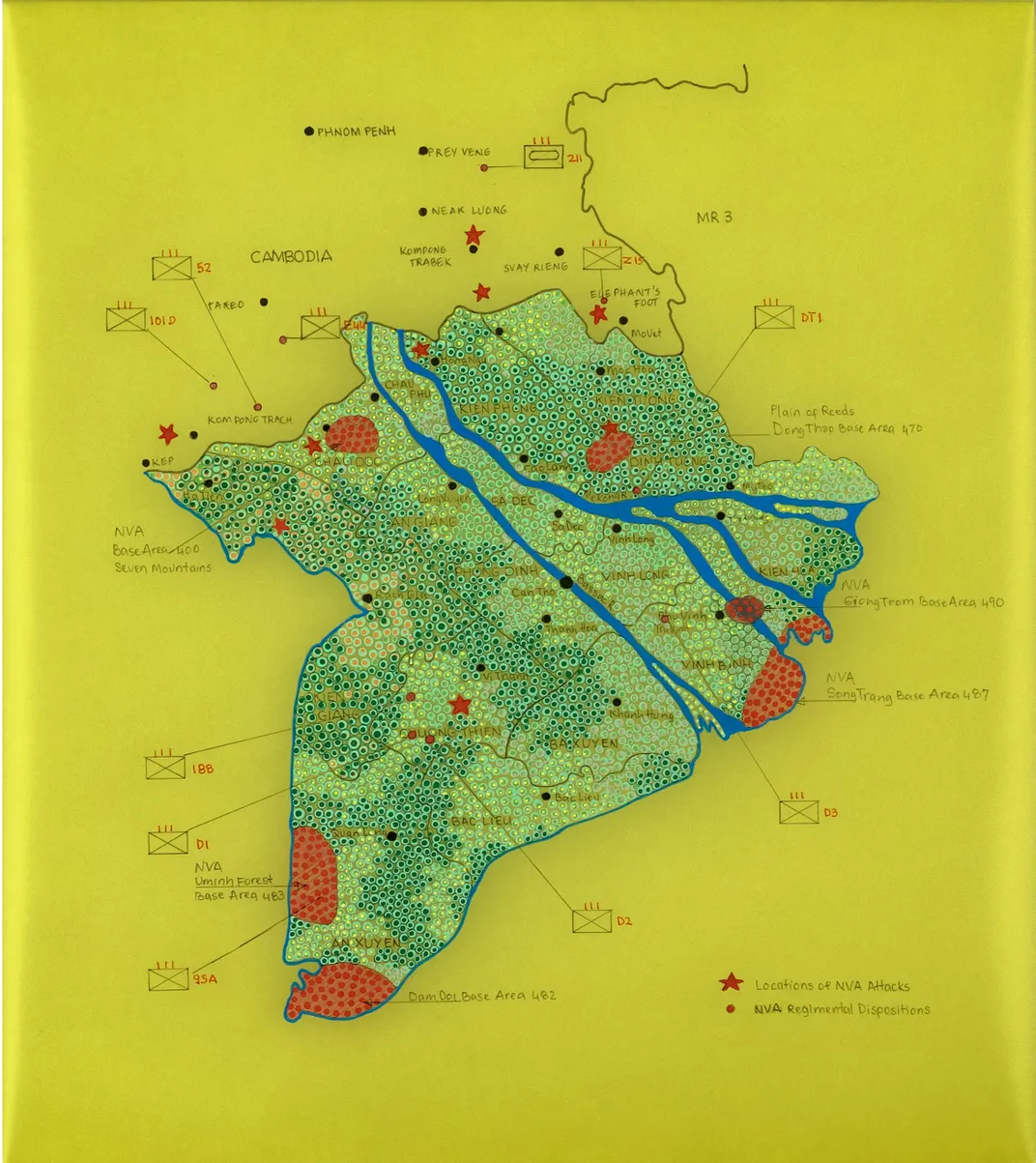

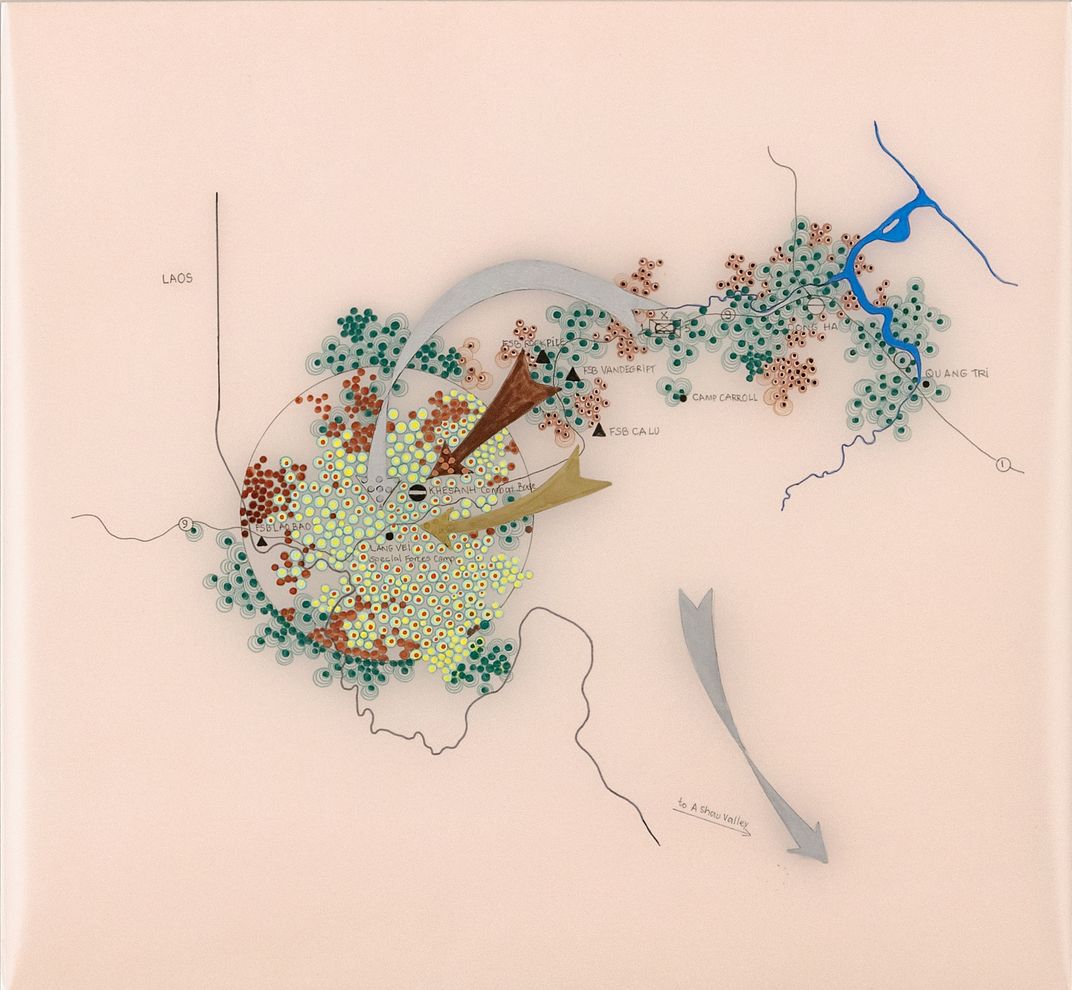

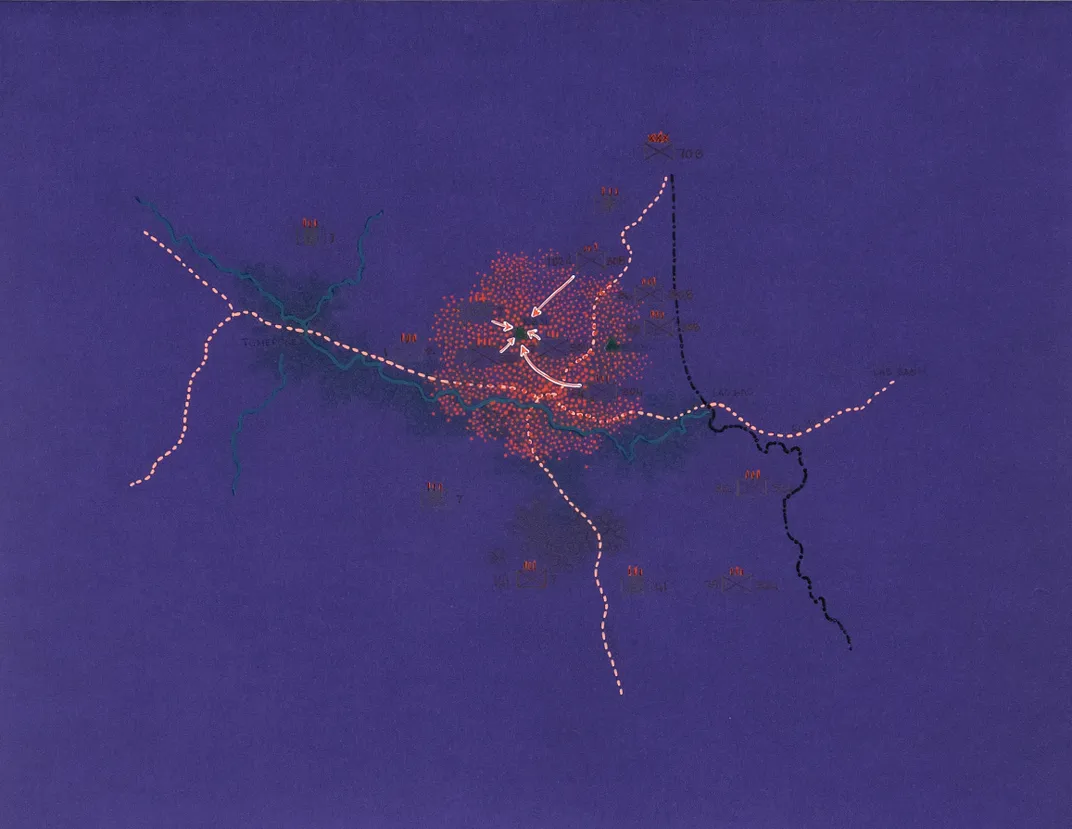

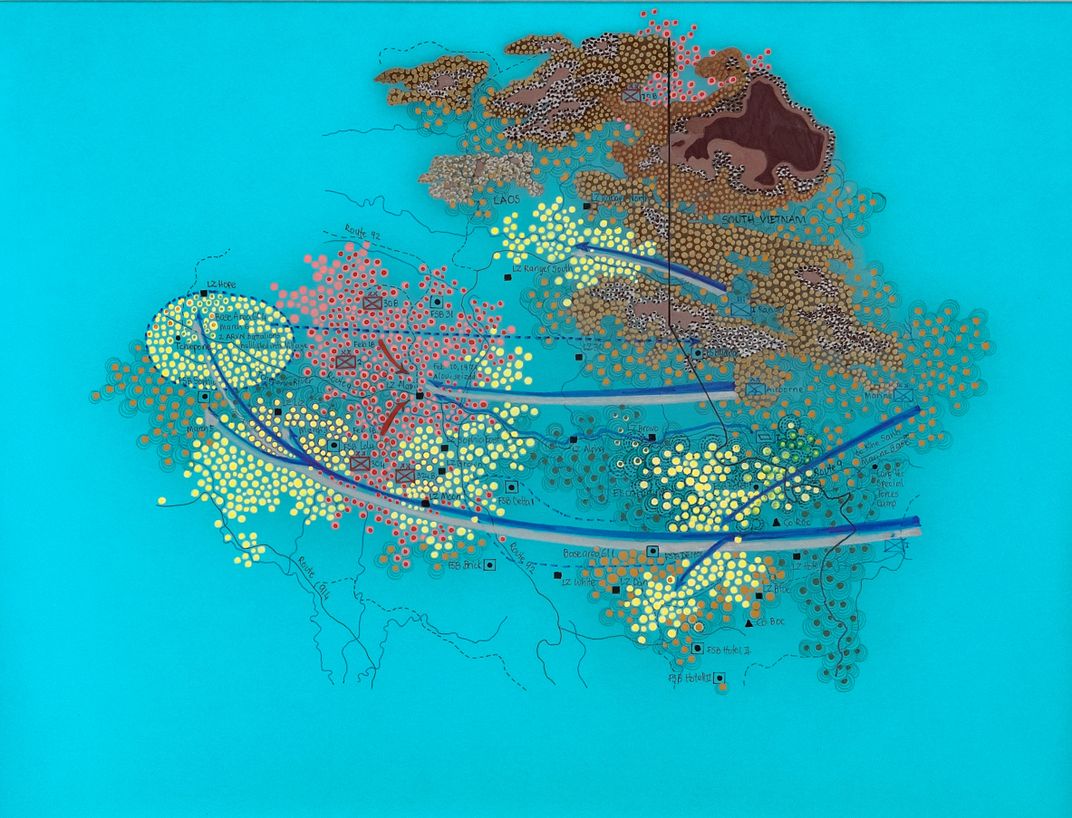

As she gathered photographs, maps and shards of information, she began to create a huge diagram, that comprise her piece Remapping History: an autopsy of a battle, an excavation of a man’s past, plotted out over 40 feet, across three walls.

Her meticulous maps, some with arrows; most without legends, become hints of various operations and attacks, with no trace of their successes or failure. They lay the land in dreamy, jewel-like colors but anonymous shapes, much like the land must have looked to pilots above, bombing it. A cartographer and archaeologist, Chung is skillful in her depictions, but purposely inexact in what she is showing.

“The places and events represented are searingly personal and historically significant, but the visual details are intentionally ambiguous,” show organizer Sarah Newman, the museum’s curator of contemporary art, writes in the 30-page catalog that accompanies the show. “As much as anything else, the maps are documents of loss, speaking to the profound inaccessibility of the past.”

Chung put in two years of study at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Geneva to research how the South Vietnamese left their homeland and spread to the rest of the world. A 12-foot long, meticulously embroidered map of the world shows the forced migration routes of the South Vietnamese by plane from refugee camps in Asia that were made through something called the Orderly Departure Program, the United Nation’s resettlement program.

Chung's The Vietnam Exodus Project: reconstructing history from fragmented records and half-lived lives depicts a “comprehensive visual summary of how Vietnam’s people and culture fanned out across the globe after the War,” Newman says.

It’s the first time the information has ever been presented this way and is based on correspondence cables and records from various governmental agencies that dealt with Vietnamese refugees. Chung’s own family ended up in Los Angeles and then Houston, where she now works. But she found that an unexpected number of Vietnamese ended up in Africa, the Middle East and Latin America.

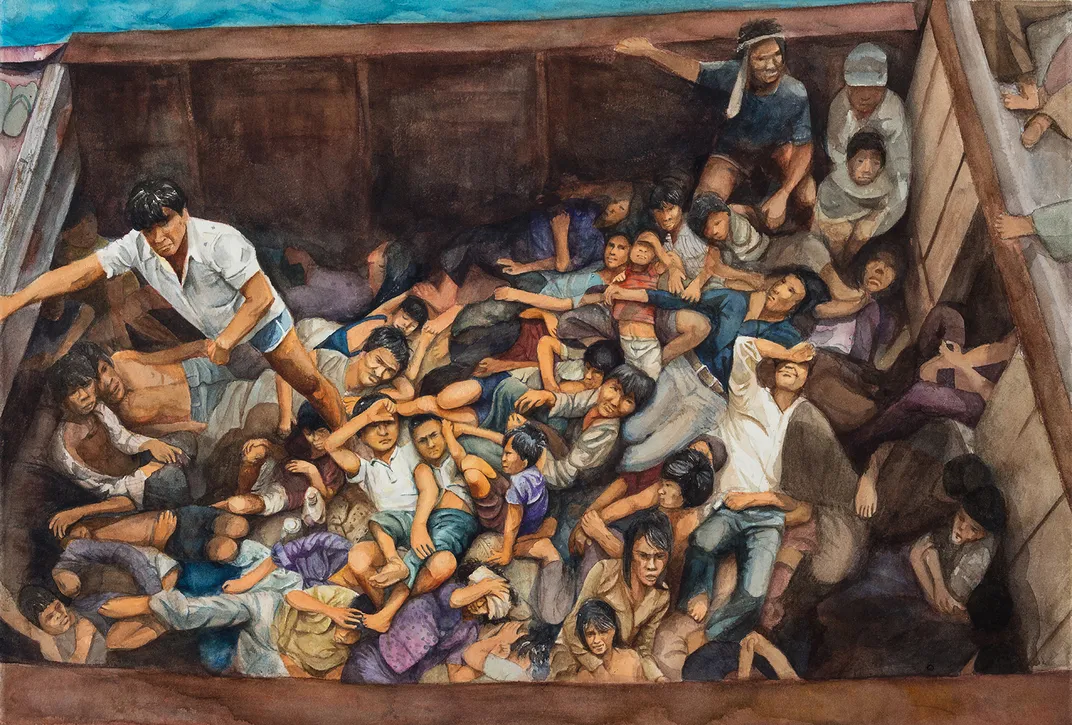

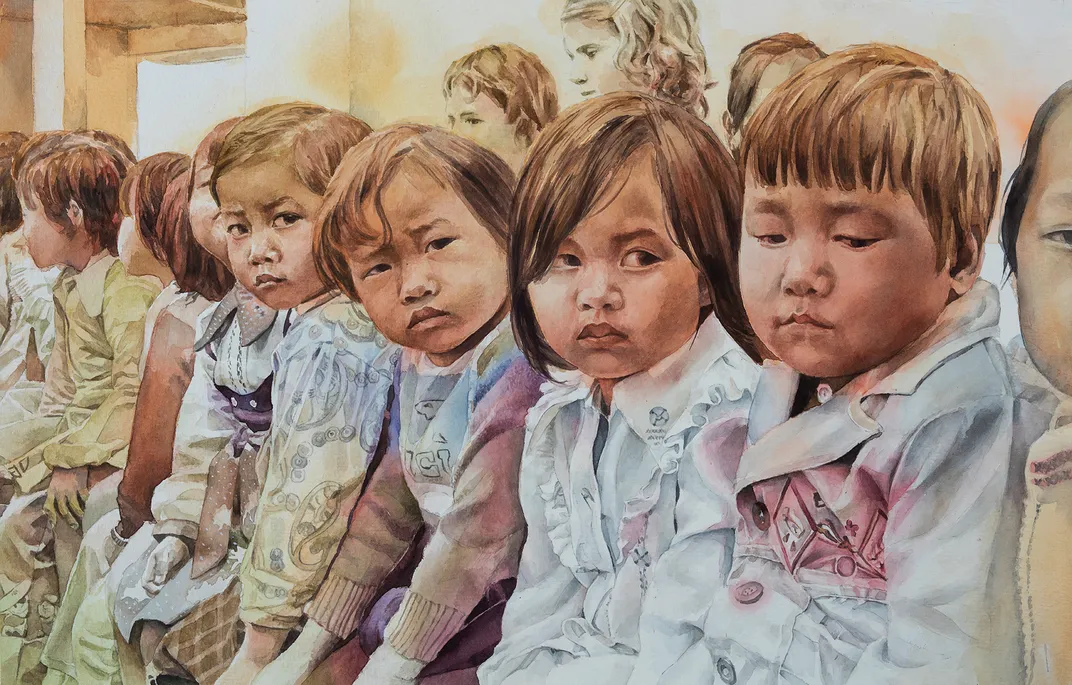

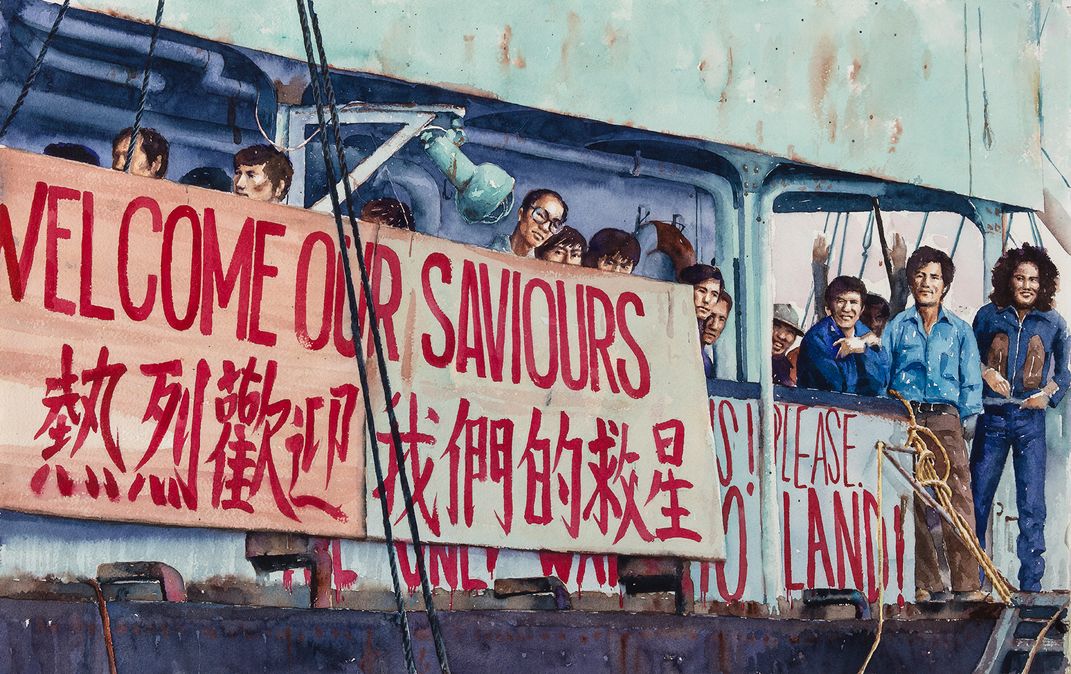

Near the dark, brooding map are a series of distinctive watercolors of the migrations, usually over water. They weren’t painted by Chung, but commissioned by her and completed by a group of young artists from Ho Chi Minh City, based on photographs of the period. Reproductions of some of the archival materials she gleaned from her research complete the piece.

But in between is a compelling video component, Collective Remembrance of the War: voices from exiles. Twelve monitors in a darkened room feature 21 former refugees from Vietnam living today in Houston, California’s Orange County and nearby Falls Church, Virginia, describing their often harrowing experiences.

“My personal quest has indeed become an entry way into the collective remembrance of the war which has left tremendous impacts on the lives of many people,” Chung says. “I’m honored to have taken on this huge task of unpacking this war through the perspective and experience of the Vietnamese-Americans that I interview and learn from. It has been my undertaking to fill up the vacuum in the narratives of this war, with the Vietnamese histories and memories which are vital in comprehending the war’s legacies, but are often ignored in the American narrative of it and omitted from Vietnam’s official record.”

“Foregrounding the voices of people who have been left out of official accounts, she asks whose stories get to be remembered and how do those stories become understood as history?” Newman says. “The exhibition is a remarkable feat of historical research and artistic imagination.”

And because it is intended as a contemporary response to a large, concurrent exhibition, “Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965-1975,” Chung is also charged with the responsibility to make a generational statement with her innovative approach.

“Even within such familiar territory, Tiffany Chung’s work shows us how much more there is to know” about the Vietnam era, Newman says. “Her exhibition opens our eyes to a history hidden in plain sight, illuminating the war and its aftermath from the perspective of those who lived through it in Vietnam, and giving voice to the mostly untold stories of the South Vietnamese on whose behalf the U.S. entered the war.”

Seeing both of the two shows in conversation, she says, “gives us a glimpse in the way ideas ripple across oceans and across generations from the 20th century to today.”

Additionally, says the museum’s director Stephanie Stebich, “this is also a project we’re delighted to put under the umbrella of our Smithsonian American Women’s History initiative, to better amplify women’s voices on the history of America.”

“Tiffany Chung: Vietnam, Past Is Prologue,” curated by Sarah Newman, continues through September 2, 2019, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. The exhibition is part of the American Women's History Initiative.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)