A Sensuous Blending of Style and Speed, This Ducati Is Both Art and Machine

An appreciation for the cognoscenti of motorcycles

:focal(731x719:732x720)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0a/d8/0ad85a3b-3de3-4277-97ab-edfcd420d60e/bgselects-10.jpg)

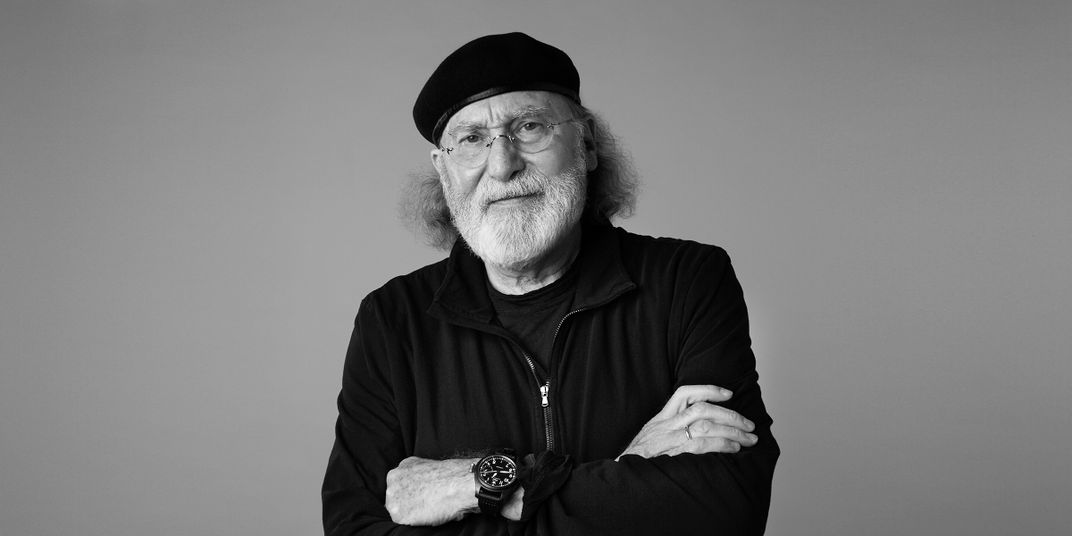

A piece of Italian sculpture capable of covering 200 miles in one hour has taken center stage this year at New York City’s Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, where Bob Greenberg, founder, chairman and CEO of the international advertising company R/GA, curated the museum’s 16th “Selects” exhibition.

That sleek creature is a Ducati motorcycle, a 2017 model called a Panigale 1299 Superleggera (leggera is Italian for nimble or agile, 1299 is the displacement of the engine in cubic centimeters, and Borgo Panigale is the name of the neighborhood in Bologna where Ducatis are produced). The machine is encased behind walls of Lucite like a holy object in a reliquary, which to the cognoscenti of motorcycles it most definitely is.

I took a personal interest in this most revered of artworks, for I have owned a total of six Ducatis in my motoring life, and each has been a prized possession that I never tired of looking at, or riding. Italians have been masters of design since Leonardo was sketching helicopters during the Renaissance, and my Ducatis, like the one in the Cooper Hewitt show, were each a sensuous blending of style and speed that gave me the dual thrills of flying down twisting California coastal roads and then stopping at cafes to the admiring eyes of my fellow bikers.

Like the other prestigious guest curators of the previous 15 Selects exhibitions, Greenberg is a dedicated design connoisseur, and so among the objects on display, most chosen from the Cooper Hewitt’s permanent collection, were also things that he owns and admires, such as products designed by one of his heroes, the famous German industrial designer Dieter Rams. One section of the show, which shortly comes to a close on September 9, is entirely dedicated to Rams’ designs, each inspired by his ten principles of good design—be innovative, useful, aesthetic, understandable, unobtrusive, honest, long-lasting, thorough down to the lasting detail, environmentally friendly and be as little design as possible. “I couldn’t tell the story I want to tell without some of the things from my own collection,” Greenberg said in a recent phone interview.

The motorcycle is the most recent addition to his personal collection. In fact, Greenberg only recently purchased the spectacular, limited-production machine, so it was the newest product on view. He owns and rides several other Ducatis, including one that once won the Canadian grand prix race, but he had yet to throw a leg over the Superleggera when he decided it belonged in the exhibition.

Part of the story Greenberg wants to tell with his selection, he said, is the “impact of technology on product design,” and the Ducati is a glamorous example, with 200 horsepower in a sleek under 400-pound package of titanium, carbon fiber and magnesium.

But it’s the inclusion of remarkable technology that led one motorcycle reviewer to call the bike “a 200 mile per hour supercomputer.” Ducati calls the system event-based electronics, and what that means is that sensors “read” the bike’s situation in real time—what’s going on with brakes, the acceleration, the lean angles in turns, and other metrics. And when the system determines that a rider mistake is about to happen—if, for instance, the rear wheel starts to spin and the bike is at a lean angle that predicts a crash—the bike adjusts on its own.

Much of this technology is adapted from Ducati’s racing teams, and its purpose is to protect those riders.

In its civilian (street) version, it helps to keep alive those who can afford the price of great motorcycles even after their reflexes are on a downward trajectory. I’ve learned this from my own experience on racetracks at an age I’d rather not specify. In a funny side note, Greenberg told me that he’d once been pulled over for going too slowly on one of his Ducatis, which makes him rarer than Sasquatch. (“I was adjusting my mirrors,” he explains.)

The Ducati echoes the memorable design ethic of the late, less-famous (at least in the U.S.) Massimo Tamburini—who understood the aesthetic of motorcycles perhaps better than anyone ever has. Though Tamburini left Ducati after many years to design another bike, the MV Agusta, the sexy looks he gave his Ducatis in the 1990s and early 2000s live on in the new, more technically sophisticated Superleggera displayed at the Cooper Hewitt. (In the popular 1998 Guggenheim Museum show “The Art of the Motorcycle,” Tamburini’s designs—a Ducati 996 and an MV Agusta “gold series”—occupied pride of place at the beginning and the end of the scores of classic motorcycles.)

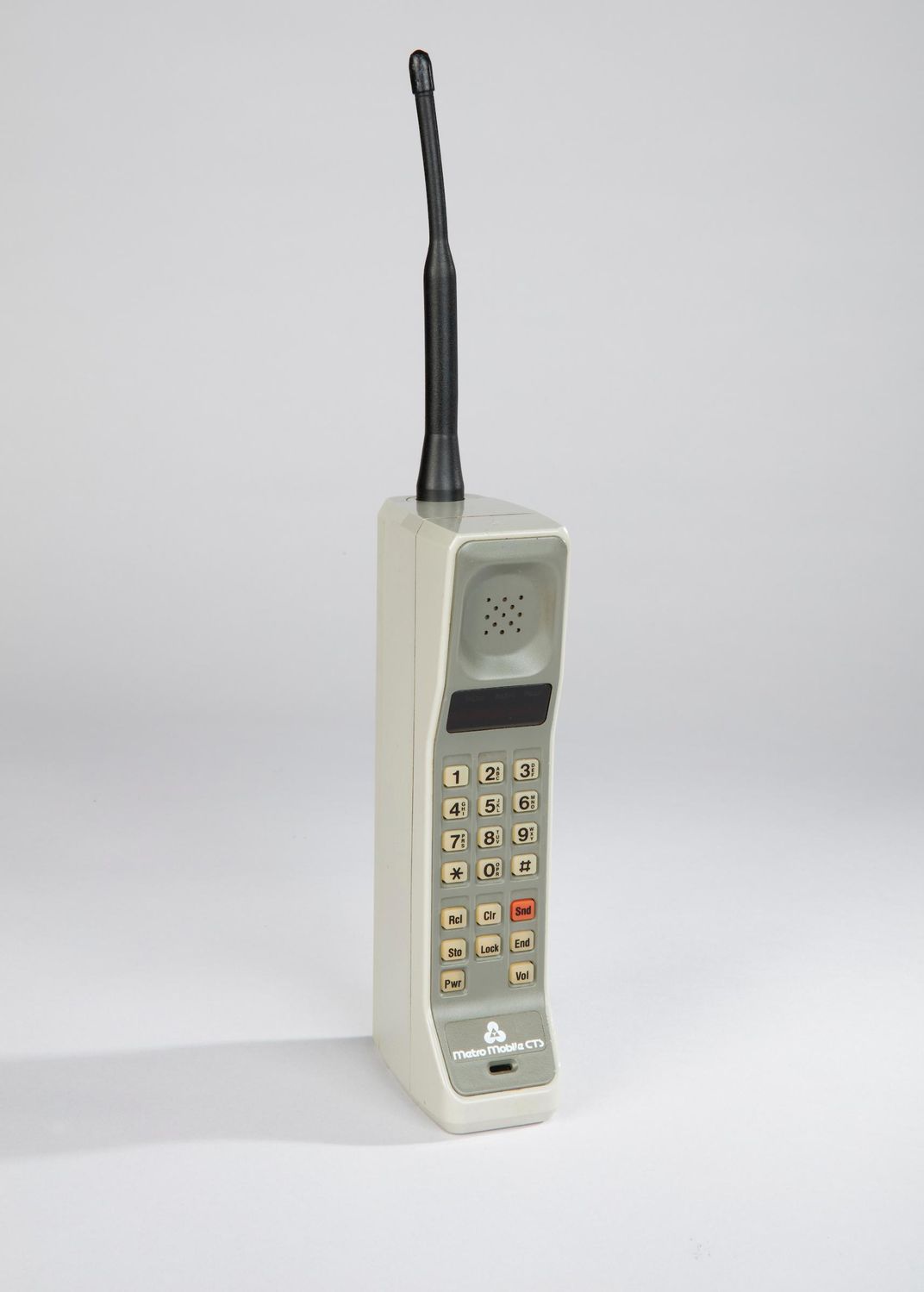

Though perhaps not as dramatic as Greenberg’s latest Ducati, other objects in the Selects show illustrated his idea of tech innovated design. There were, for instance, a Polaroid SX-70 instant camera, the first cellular phone by Dynatac, and a once-innovative 51-year-old pinwheel calendar. Greenberg told me that he has donated some of his own collection to the Cooper Hewitt.

Greenberg’s life and work are informed by his love of design. According to his co-workers at the R/GA agency, there are motorcycles on display at the Manhattan offices. And in working with the architect Toshiko Mori to build his house in upstate New York (she also designed the Cooper Hewitt show), he applied ideas that his company has developed to build digital websites to the plan for the mostly glass compound.

“A website and a house are really the same thing,” he told me. “One is virtual space, and one is real space, but that’s the only difference.”

“My idea for the products in the exhibition,” he says, “is to show what happens when great design is disrupted by technology. And to show that design and technology combined have changed the world.”

“Bob Greenberg Selects” is on view at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, located at 2 East 91st street at Fifth Avenue in New York City, through September 9, 2018.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)