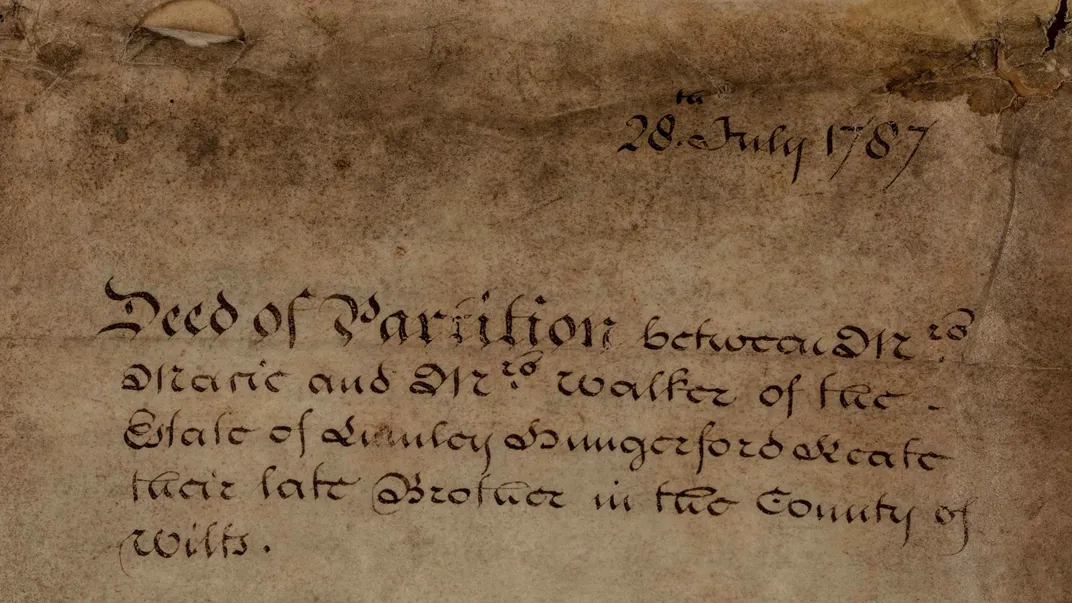

When the 1787 Hungerford Deed reached the Smithsonian Institution Archives in 2019, its 16 folded parchment pages were stiff and difficult to open, but it soon became clear that the document offered new insight into the family life of the Smithsonian’s founding donor. James Smithson, who left his fortunes to the United States “to found in Washington, . . . an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge,” was the illegitimate child of the first Duke of Northumberland and Elizabeth Hungerford Keate Macie. In the late 18th century, his mother and her sister went head-to-head in court over ownership of property springing from their ancestral roots in the Hungerford family, which had been prominent in the medieval era.

Today, to mark the Institution’s 175th anniversary, the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives launches the virtual exhibition “A Tale of Two Sisters: The Hungerford Deed and James Smithson's Legacy,” providing viewers an opportunity to “turn the pages” of this recently recovered document. The new website offers a deep dive into the deed, sharing biographical insight into some of the players as well as explanations of legal processes and background on social customs of the era. William Bennett, a Smithsonian Archives conservator, calls it the “next best thing to turning the pages yourself with an expert at hand to offer context and to highlight points of interest.”

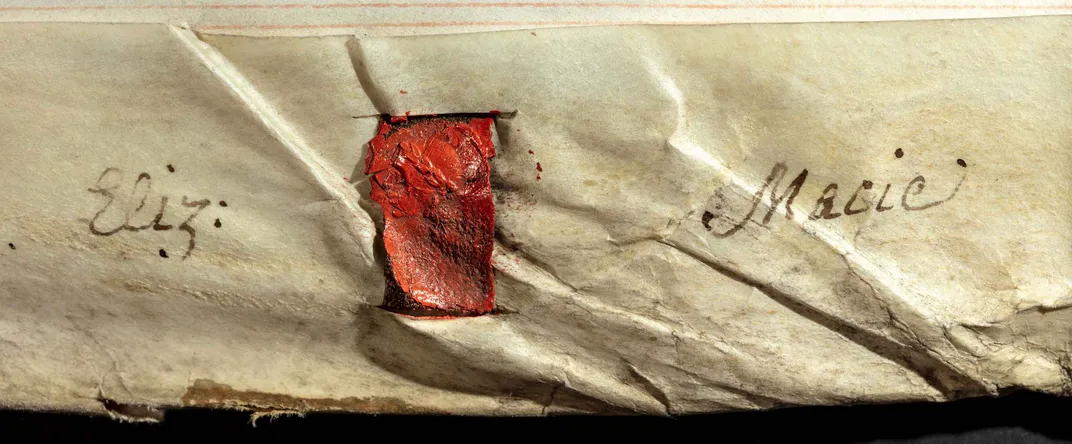

Upon its arrival as an anonymous gift to the Smithsonian, the deed thrilled Bennett. “It shows you so much of the material culture of this place in time,” he says, and it offers a view of “these people’s daily lives, what their milieu was like.” As someone whose chosen career focuses upon the protection of old documents, Bennett was delighted by an unexpected treat. “To learn that it’s connected to history of the founder just pushed it over the edge for me in terms of its interest and appeal. It has Smithson’s signature on the back under his birth name, which is awesome.” Because the unexpected pandemic took him away from typical hands-on conservation work in the archives, Bennett made the most of a greater opportunity to research the deed and analyze its history.

As a witness to the deed, Smithson played a role in its finalization, and he signed it, James Louis Macie, the name his mother chose for him when he was a baby (and which he kept until he was in his mid-30s). To obscure his parentage, she had given him the last name of her late husband, even though John Macie had died several years before Smithson’s birth.

“There are many clues that Smithson's illegitimacy troubled him all his life,” says Heather Ewing, author of The Lost World of James Smithson: Science, Revolution, and the Birth of the Smithsonian. “He grew up in a society structured around privilege, with a mother obsessed with status and ancestry.” Ewing believes his status made him an outsider and perhaps contributed to his choice to bequeath his wealth to the United States. “This country—on paper, at least—espoused ideals of equality and would have seemed to Smithson a place where being illegitimate would not have been such a handicap. He imagined a country that valued science and self-government—rather than one that was organized around heredity and religion—would be the best executor of his gift, intended to benefit all humankind.”

Despite the onus of his illegitimacy, Smithson prospered as a chemist and mineralogist. He is known for his study of zinc ores or “calamines,” and the mineral zinc carbonate was, in fact, later renamed Smithsonite to honor him and acknowledge his work. Smithsonite was important in the production of brass. Smithson led a busy life but never married or had children. As a result, when he died in 1829, his will left his fortune to his nephew or with the principal reserved for the nephew’s future heirs. But the nephew died in his 20s, just a few years after Smithson, without having had any children, and thus the extraordinary secondary clause in Smithson’s will was activated, bequeathing Smithson’s estate to the United States. Smithson’s money arrived in 1836 and after a decade of Congressional debate finally gave birth to the Smithsonian, which is now the largest museum and research complex in the world, with 19 museums and numerous research facilities.

The Hungerford Deed demonstrates the passion of Smithson’s relatives and their strong desire to validate connections with Hungerford family history. One member of the family, Thomas Hungerford, was the first recorded speaker of the House of Commons in 1377. Like some other members of the family, he had connections to royalty, and for a time, the Hungerford family owned a great deal of property in western England.

Over the centuries, the family’s social standing gradually declined. And yet, the Hungerford name remained important to Smithson’s mother and her family. She had Hungerford as part of her given name, and her sister, Henrietta Maria Walker, changed her surname to Hungerford late in life. Smithson himself bankrolled the creation of a Hungerford Hotel in Paris in the 1820s, and he also requested his nephew and heir change his name to Hungerford.

The purpose of the deed was to confirm the partition of the ancestral Hungerford properties between the two sisters (James Smithson’s mother and aunt). It documents a dispute that began in the 1760s when their brother, Lumley, died without a will. That fight dragged on for decades as the sisters battled first other family members in court to gain ownership of the land and then each other to determine how to split the properties between themselves.

For a long time, historians knew little about Smithson’s mother. The many lawsuits in which she was named “give us the best window we have into her life and what was important to her,” says Ewing. “She was proud, defiant, and tempestuous—all of the lawsuits against her accuse her of making threats and outbursts. And yet she was witty and charismatic—enough to captivate the Duke of Northumberland in a years-long affair.” Moreover, “she was keenly aware of how much was stacked against a single woman of property and felt that most everyone was out to get her. Smithson also was good at holding a grudge—perhaps he got that from her.”

The story unfolds in the deed, making clear that after years of squabbling, the sisters agreed that an outside party would decide how to divide the property. Because the sizes of the individual properties made it impossible to distribute equally, the sisters consented to a drawing of lots and accepted a plan that said whichever sister got the smaller share would receive compensation from the other. Smithson’s aunt, Henrietta Maria, won the bigger share but for some unknown reason failed to report to court to finalize the deal—and even when her sister took her to court for her inaction, she did not come forward to support her case. Her inaction led to the completion of this deed, which requires execution of the property partition and demands that Henrietta Maria pay her sister.

While it is impossible to know how much the property battle affected Smithson, it played out over many years, beginning when he was an infant and concluding when he was studying at Oxford. “His entire childhood and young adulthood was shaped by his mother's fierce pursuit of these ancestral properties,” says Ewing. Smithson's choices in life reveal how much he “was concerned with the pursuit of legacy—of both name and property—as well as the pursuit of knowledge.” His mother’s reasoning offered him a clear message: “Family heritage was everything—money, security, identity,” Ewing writes in her book.

Smithson’s family took great pride in its connection to the Hungerfords. Even today, descendants of the family remain interested in their heritage. They still hold family reunions in different places around the world, and on June 10 and 11, 2019, more than 30 family members from places as diverse as England, Canada and Australia gathered at the Smithsonian to see the product of Smithson’s donation, and at that time, they had a chance to view the Hungerford Deed.

Before closely examining the deed, Bennett expected it to be full of legal jargon, but to his surprise, he found that about half of the document represented a family history. The document, which had been stored in a folded shape for more than 200 years, is composed of parchment pages bound at the bottom by string and ribbon. Bennett enjoys working with parchment, which is made from dried animal skins that have been chemically treated. However, it does raise conservation issues, which determined what steps were needed to make the document more accessible. “Parchment doesn’t really like changing shape after it’s settled into something that it’s used to,” says Bennett. “It was very comfortable, and it took a lot of effort for us to be able to open it up and read it carefully.”

The deed came to the Smithsonian with a description on the back along with several names and a note that said, “Smithsonian bequest.” Archives employees took an early peek at its content before any conservation work had been done. Then, Bennett turned his attention to necessary steps that would help it lie flat. “Because the outside was the most exposed, there was some damage on the corners of this folded package,” says Bennett. There was water damage, too.

The first phase of conserving the document required about two weeks of careful work. The immediate goals were to flatten and repair it. Bennett used moisture to enable the document to relax. He carefully treated each sheet, using a gently humidified sheet of cotton blotter to deliver moisture through Gore-Tex. As he worked, polypropylene sheets separated a treated layer from the other sheets to avoid distortions. At the same time, he tried to protect the deed’s tax stamp seals. (These were the product of the same Stamp Act that so angered revolutionary Americans.) Abrasion and water damage made some sections of the document difficult to decipher, so the archives’ transcription is incomplete.

The document requires additional conservation work to flatten it more, to repair damaged areas, and to protect a wax seal apparently applied by Smithson’s mother. Nevertheless, the content has made it an exciting discovery. “It was this sort of neat little gift, if you will,” says Bennett. “It’s this little package that we got to have the opportunity to unwrap.”

Visit the virtual exhibition “A Tale of Two Sisters: The Hungerford Deed and James Smithson's Legacy,” from the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ba/b5/bab511ca-a2cb-41e9-af8b-b46912d66843/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e4/79/e479615b-e269-4f09-9a5d-2da89ebf33d9/longform_desktop.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)