Mr. Smithson’s Family Goes to Washington

A contingent of descendants, related to the founder of the Smithsonian Institution, embarked on a tour of the museums

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/21/f52129a4-560a-447d-86fd-cfedafd4e439/img_0862.jpg)

Earlier this week in Washington, D.C., more than 30 distant relatives of the 18th-century British scientist James Smithson crowded the lobby of the Smithsonian Castle building. Unfurled before them was a genealogy tree dating back several centuries for the Smithson and Hungerford families. Each of the members crouched over the document, searching for their place among the clan.

Smithson, who founded the Smithsonian Institution, was born in 1765 to Elizabeth Keate Hungerford Macie and was the illegitimate son of Hugh Smithson, who later became the Duke of Northumberland. James Smithson’s mother was descended from Henry VII of England, but James was one of a reported four children conceived out of wedlock by his father, according to Smithson biographer Heather Ewing. He and his siblings were never recognized by the Duke of Northumberland, and the descendants had long struggled to place themselves within the larger family.

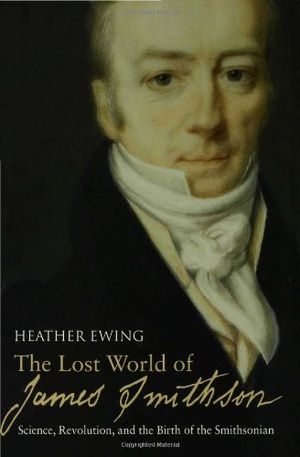

That made the gathering of several dozen Smithson relatives in Washington, D.C., all the more triumphant. Their arrival from both the United Kingdom and British Columbia, Canada, where most of Smithson's relatives are now living, had been a year in the making. Much of it is owed to Ewing’s 2007 biography The Lost World of James Smithson, which made the family history—long a forgotten point in the Hungerford lineage—a central part of its story.

The Lost World of James Smithson: Science, Revolution, and the Birth of the Smithsonian

Drawing on unpublished diaries and letters from across Europe and the United States, historian Heather Ewing tells James Smithson's compelling story in full. The illegitimate son of the Duke of Northumberland, Smithson was the youngest member of Britain's Royal Society and a talented chemist admired by the greatest scientists of his age. At the same time, however, he was also a suspected spy, an inveterate gambler, and a radical revolutionary during the turbulent years of the Napoleonic Wars.

Patrick Hungerford, who lives in England and is a descendant of one of James Smithson’s siblings, discovered the book on a friend’s recommendation. As he sifted through the genealogy that Ewing had traced, he realized that his connection to the namesake of the Smithsonian Institution was real. While the Hungerfords knew their connection to British royalty well—many keep a copy of the 1823 family history Hungerfordiana, according to Ewing—history had obscured the Smithson connection.

"I didn't know there was a connection with the Smithsonian," says George Hungerford, one of the descendants. But after the first few family members read Smithson’s biography, he said that everyone else clamored for a copy.

“It’s wonderful after 12 years to have people discovering it and having such a personal strong connection to it,” Ewing says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/65/876526ca-8cf3-4dc2-865d-2cb66c6bc3e0/saam-195971_1.jpg)

Upon his death in 1829, James Smithson had designated his nephew Henry James Hungerford as the heir to his considerable fortune. But his will carried a most unusual stipulation: Should his nephew die without children, the money was to be given over "to the United States of America, to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men." Hungerford indeed died without an heir, and so his estate came to the United States. Smithson never specified exactly how such an institution of knowledge would look or be defined. Today, the Smithsonian Institution is a sprawling complex of museums, research centers and libraries with international connections around the globe.

The sum of Smithson’s fortunes amounted to a staggering $508,318.46—roughly equal to about $14 million today, a sum that represented a full 1.5 percent of the total U.S. federal budget and rivaled at the time the endowment of Harvard University, which at that point was already almost 200 years old. When Smithson died in 1829, his bequest made the pages of the newspaper New York American, but only in 1835, when Henry James Hungerford died without children, did the bequest become effective.

A geologist and a self-trained chemist, Smithson, who was educated at Oxford, published 27 papers throughout his life on everything from the chemical structure of a woman’s crying to a new method for brewing coffee. Most significant was his 1802 discovery of a zinc ore that was posthumously dubbed "smithsonite."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/36/e5/36e56eab-5b21-4310-b931-6a546ce53279/img_0861.jpg)

In life, Smithson never visited the U.S., nor did he have any kind of familial connection to it. So, what inspired him to leave such a sizable endowment to the United States?

As Ewing pointed out in the biography, one likely explanation is that Smithson admired the U.S. not only for its innovative scientific community, but also for its renunciation of aristocratic titles.

“Many of the men leading the charge for modernity stood on the margins of society,” Ewing wrote. “Science for them became the means of overthrowing the system as it existed, of replacing a corrupt order based on superstition and inherited privilege with one that rewarded talent and merit—a society that would bring prosperity and happiness to the many rather than the few.”

Throughout his life, Smithson struggled to make peace with his illegitimate birth. To many Europeans, including to Smithson, the U.S. seemed to promise an escape from that strand of insular family politics that prioritized the nature of one's birth above all else. “Here finally he was witnessing the rebirth of a nation predicated on the idea that the circumstances of birth should not dictate one’s path in life,” Ewing wrote.

Part of the reason for the enduring mystery surrounding Smithson's motives is that his papers and some of his personal effects were burned in the tragic 1865 fire that engulfed the Smithsonian Castle. Ewing joined the family on their tour of the Castle and Smithson's family members visited the study where the Smithson papers were housed, where Ewing explained that, in addition to the papers, the founder’s wardrobe was among the items burned—including, amusingly, two pairs of underwear the founder had owned upon his death.

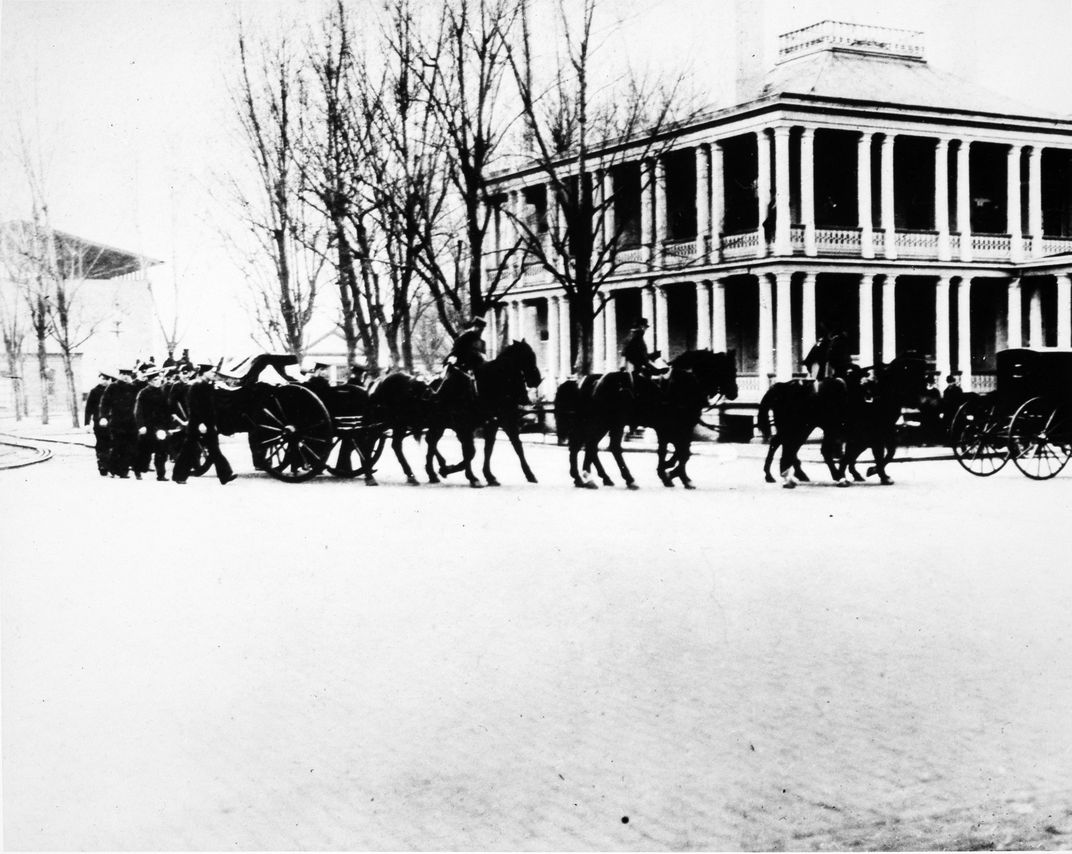

After leaving the study, the group traveled down to a vestibule, located just at the entrance of the Castle, where Smithson's remains are entombed in an ornate sepulcher. Seventy-five years after Smithson’s death in 1829, inventor Alexander Graham Bell, who served as a Smithsonian Regent from 1898 to 1922, went to Italy to retrieve Smithson's body from its resting place in Genoa, Italy. In January 1904, Bell’s ship along with the Smithson casket arrived at the Navy Yard and a calvary detachment traveled the length of Pennsylvania Avenue to deliver Smithson's remains to the Smithsonian Castle.

When the National Intelligencer first told the American public about the bequest, it notably described Smithson as a "gentleman of Paris," neglecting to mention his British heritage. But it was not lost to many American senators, who at the time were loath to take money from a descendant of the British crown. Debate ensued in Congress about whether to accept the bequest at all. Finally in 1836, the U.S. Congress dispatched an emissary to London to bring back the money. The fortune—all in gold sovereigns—arrived in New York City aboard the packet ship Mediator, two years later.

It's an implausible story with a curious ending and that's where the descendants of Smithson were left—touring an American museum created by their British ancestor, whose pivotal donation still remains one of the most defining philanthropic moments in history.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.