A Look Back at the First Time the Smithsonian Castle Closed for Renovations

In February, the building will shutter for five years for much-needed improvements

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ca/d3/cad349aa-b89c-4ab7-b7e2-0c4a84132618/sia2013-08351web2.jpg)

Strategically located in Washington, D.C., on the National Mall is a red brick building completed in 1855 and called “The Castle” because of its medieval revival design and architecture.

The historic edifice, the original home of the Smithsonian Institution and the offices of all 14 Smithsonian secretaries, will close this year, beginning February 1, for its first major renovation in more than 50 years.

The modernization project, upgrading the building’s security and information technology, along with its mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems, and including window replacement, roof restoration and repairs to its exterior stonework, is expected to last about five years. A restoration of the building’s magnificent Great Hall will offer visitors a dramatic new experience, returning the chamber to its original splendor with the removal of a 1968 addition of second-floor office spaces, gleaming terrazzo floors and other decorative finishes. The building’s café and stores are to be redesigned in an expansive move to the building’s lower level.

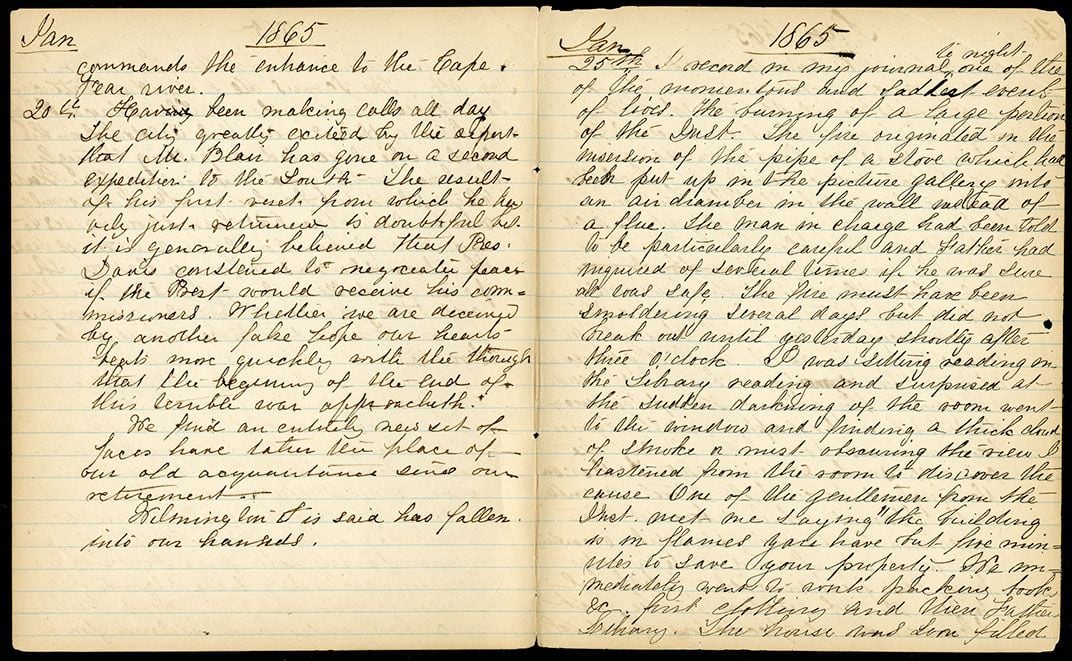

The story of this National Historic Landmark began in 1855. With its rusty red color and craggy sandstone, likely cut by enslaved labor, from the cliffs of Maryland’s nearby Seneca Creek, its halls became the home and haunt of the Smithsonian’s first secretary, a prominent scientist named Joseph Henry, who lived there with his family. His daughter Mary, famously kept a diary of the lively events occurring at this location during the Civil War. Ten years later, a devastating fire would nearly consume the building, a conflagration that to this day remains etched into the sinew and bone of the Institution’s history.

Joseph Henry was a man of many talents (and flaws)

The Smithsonian's first secretary was known to advise the United States President Abraham Lincoln on a variety of things, ranging from the use of observation balloons in wartime and proposals for new armaments, to the mining of coal in Central America. Joseph Henry was even asked to investigate a medium who conducted séances for Mrs. Lincoln—and uncovered the trickery employed. President Lincoln often visited Henry in the Castle, and at least on one occasion the pair climbed the north tower to test a light signaling system, whereby warnings of a possible Confederate invasion of the capitol could be flashed from the Smithsonian to Fort Washington to the south, the U.S. Capitol, and the Old Soldier’s home—where Lincoln spent the summer months.

The Castle’s location near the Potomac River and adjacent Virginia was so strategic that in April 1861, Secretary of War Simon Cameron instructed his chief ordinance officer to issue “professor” Henry 12 muskets and 240 rounds of ammunition to defend the Smithsonian. The Castle also hosted an acoustically marvelous 2,000 seat auditorium, which was the site in late 1861 and early 1862 of a series of lectures by prominent abolitionists including Wendell Phillips, Horace Greeley, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Ward Beecher, among others. President Lincoln and many prominent officials attended. Henry, however, would not include Frederick Douglass, who was to be the final speaker in the series participate, reporting, “I would not let the lecture of the coloured man to be given in the rooms of the Smithsonian.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6a/62/6a62606f-4f6c-4ba0-9bd8-c4081cb44859/sia2011-2391web.jpg)

The fire smoldered out of sight

It was January 24, 1865, and a bitter cold had descended on Washington, D.C. The Civil War had reached a turning point and Lincoln had won re-election just months earlier. That afternoon an event took place that was so horrific that Congress adjourned for the day as city residents rushed to the Smithsonian grounds.

Only days before, workmen had been carrying out some repairs in the Castle’s cold and drafty “Picture Gallery,” where some 200 of John Mix Stanley’s magnificent paintings of American Indians, among other artworks, were installed in the popular salon-style of the day. Needing to keep warm, the workers connected a wood-burning stove to what they thought was a flue. But instead, it was the brick furring space behind the wall. Embers from the stove smoldered out of sight, probably for several days before the tragedy struck.

On the afternoon of the 24th, the walls of the Smithsonian Castle Building suddenly burst into what was described at the time as a “sheet of flame.” Custodian William DeBeust sounded the alarm and managed to save a handful of paintings before retreating from the inferno. The fire quickly spread to the “Regents Room,” where the Smithsonian’s governing board typically met, and destroyed some of the rare personal effects that had belonged to the Institution’s British benefactor James Smithson.

The flames roared through the “Apparatus Room,” housing scientific equipment, as well as Secretary Henry’s office, consuming his irreplaceable papers, documents and correspondence. It burned through the Smithsonian’s great auditorium—the largest in Washington. A cautious Henry had instructed his staff to store buckets of water around the Castle in case the building ever caught fire, but the huge conflagration rendered the plan futile.

The fire rose to the Castle’s wooden roof, causing its collapse, along with a tower and several battlements. Mary Henry, the secretary’s daughter described the scene:

Truly it was a grand sight as well as a sad one, the flames bursting from the windows of the towers rose high above them curling round the ornamental stone work through the arches and trefoils as if in full appreciation of their symmetry, a beautiful fiend tasting to the utmost the pleasure of destruction.

Washington was shocked to see the blaze

Among the thousands of city residents gathered on the snow-covered pleasure garden grounds—now known as the National Mall, witnessing the catastrophe, was photographer Alexander Gardner, who took the only known image of the blaze consuming the famous building. Steam-powered fire engines had difficulty pumping water to squelch the blaze, but finally, by evening, the fire abated.

Fortunately, Col. Barton Alexander, who had managed the Castle’s completion after the original architect James Renwick was dismissed from the job, had prudently used iron for some of the Castle’s main section pillars and beams, which prevented the edifice from completely collapsing. The fire was confined to the main section and upper stories of the building, and though the losses were major, the damage to the collections in the valuable library and museum areas on the lower floor was limited, caused largely by water. Henry and his family, who lived in the building, and a number of staff dragged out furniture and whatever else they could salvage. But by the next morning, Mary Henry noted the scale of the destruction—she could look up through the shell of the Castle and see blue sky.

Much was lost, but not all

Secretary Henry moved immediately to shelter the Smithsonian’s building and its collections. Given Henry’s relationship with Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton quickly responded.

General Daniel Rucker was ordered to assist with U.S. Army troop support. Under the guidance of Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs, soldiers took tar-soaked felt and re-roofed the Castle in just three days—a tremendous feat. Henry and others were much relieved, though they later received a bill for a then-considerable amount of $1,974 to reimburse the government for the repairs.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/31/183176d4-8965-4a66-9841-617afda08af0/sia2011-2393web.jpg)

On February 5, 1865, some ten days after the Smithsonian fire, Alexander Gardner—who took the photograph of the Castle ablaze, hosted Lincoln in his studio for what would be the president’s last formal sitting. This generated the famous “cracked plate” portrait of Lincoln (now held in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery). Lincoln, though visibly exhausted from the nation’s tribulations, nonetheless managed a slight smile and even exuded a bit of optimism, as he looked forward to war’s end and the country’s rebuilding.

After the Civil War, Henry renovated the Castle, replacing the temporary roof with a permanent one. He decided not to rebuild the auditorium, as the lecture series and his refusal to let Douglass attend caused much consternation. Instead, he turned it into an exhibition hall.

The Castle, of course, has evolved in its purpose, and the Smithsonian has grown enormously over the past 150 years since that fire (21 museums and galleries, nine research facilities and a Zoo). And sometimes history comes full circle, indicating how much our country has changed, and grown.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/kurin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/kurin.png)