A Major Retrospective of Photographer Irving Penn Includes Previously Unseen Works

At the Smithsonian American Art Museum, view works from the master photographer’s 70-year career

In 1975, New York’s Museum of Modern Art mounted an exhibition of photographs depicting crushed cigarette butts collected from the streets of Manhattan. In an era when smoking was still considered cool, the large-scale close-ups of torn paper and twisted bits of tobacco stripped the cigarettes of their sexy cache, while at the same time elevating street trash to a subject worthy of the attention of a master photographer. As if to drive the point home, the pictures were printed using a solution of the precious metal platinum, a throwback method that required extreme precision and patience.

The artist was Irving Penn, who remains best known for his haute couture pictures in Vogue—images that appear side-by-side with his portraits of street trash in a major retrospective at the Smithsonian American Art Museum that includes rare images from the 1930s and 1940s, many of which were never published.

But while today Penn’s status seems firmly established, back in the 1970s, photography itself was still considered not quite worthy of the full museum treatment. It was inevitable that Penn’s MoMA show would attract controversy.

“Photographs of things such as old cigarette butts meticulously printed using expensive metals. . . . seemed an ironic and even rude comment on the world of fashionable luxury for which Penn had previously worked,” writes the Smithsonian exhibition’s curator, Merry Foresta, in an accompanying essay. “Some critics wondered if this work, intended for the gallery wall rather than the printed page, overstepped the bounds of commercial art while sullying the redoubts of high art.”

Today’s museumgoers, however, see photography as one of the main pillars of contemporary art, and they are more willing to accept a certain fluidity between commerce and fine art. And that, Foresta argues, is thanks in large part to Penn. “For 70 years, he put forth extraordinary pictures,” she says. “If you were building a pyramid, he would be at the base of our whole visual culture.”

Odd Juxtapositions

Irving Penn was born in New Jersey in 1917, the son of a watchmaker and a nurse. As a student at the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art in Philadelphia in the 1930s, he scored a coveted internship at Harper’s Bazaar, which after graduating he parlayed into a successful few years as a designer and illustrator.

In 1941, Penn made the abrupt decision to move to Mexico and become a painter, but he returned about a year later having given up the idea—his skill with a brush, he was forced to acknowledge, would never meet his own exacting standards. Still in his 20s, Penn was poised for a lifelong career as an art director at one of the big New York glossies. Photography came almost as an afterthought.

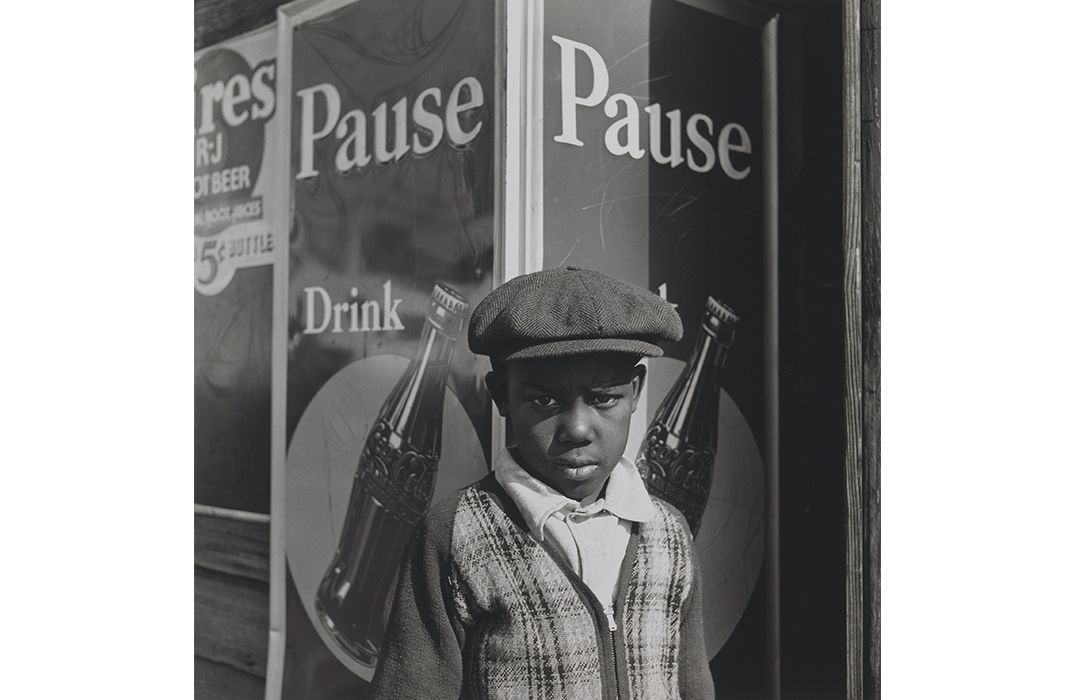

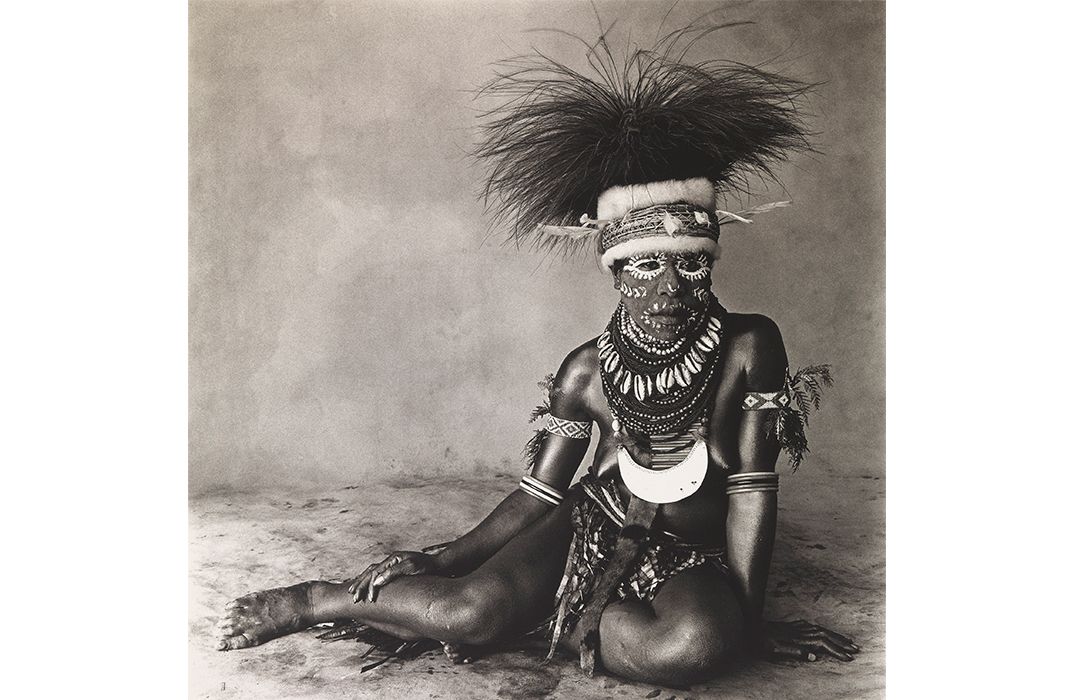

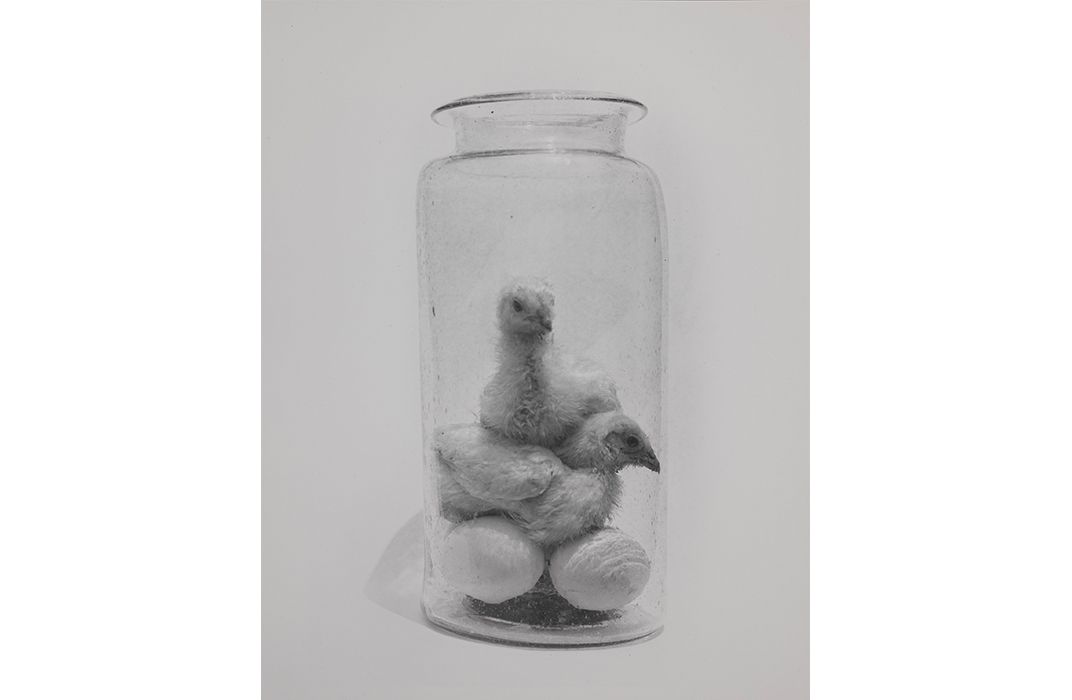

He had begun taking pictures a few years earlier, wandering New York and Philadelphia making what he described as “camera notes, more to remember what I saw than with serious photographic intent.” Then, traveling through Mexico and the American South, he captured portraits and street scenes that seemed to combine photography’s journalistic mode with more surrealistic impulses.

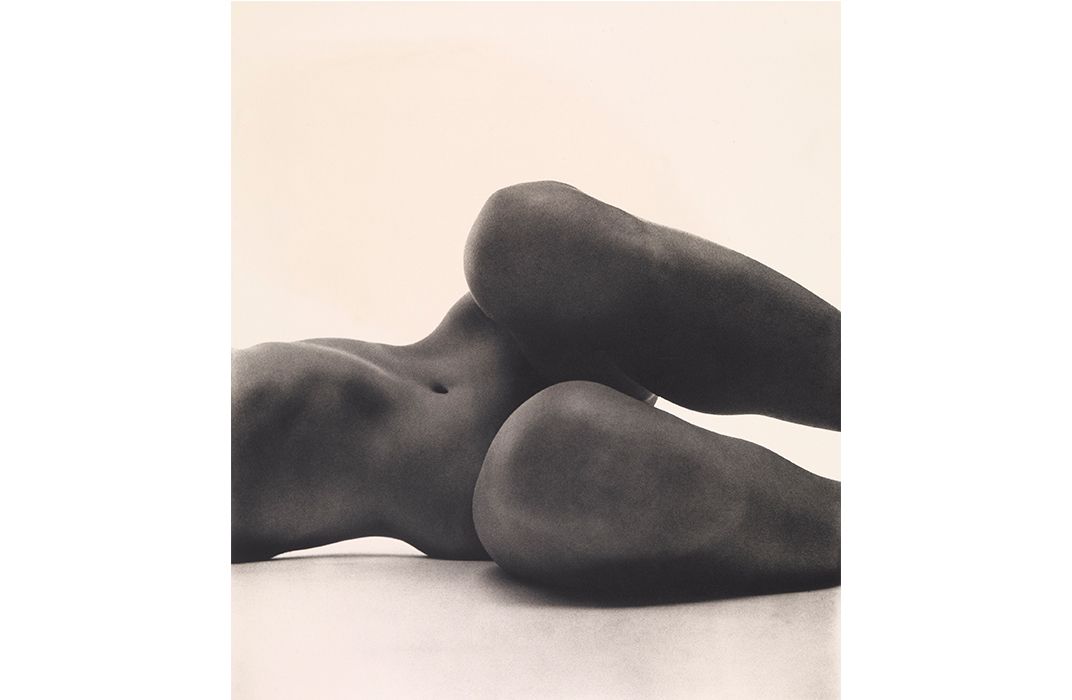

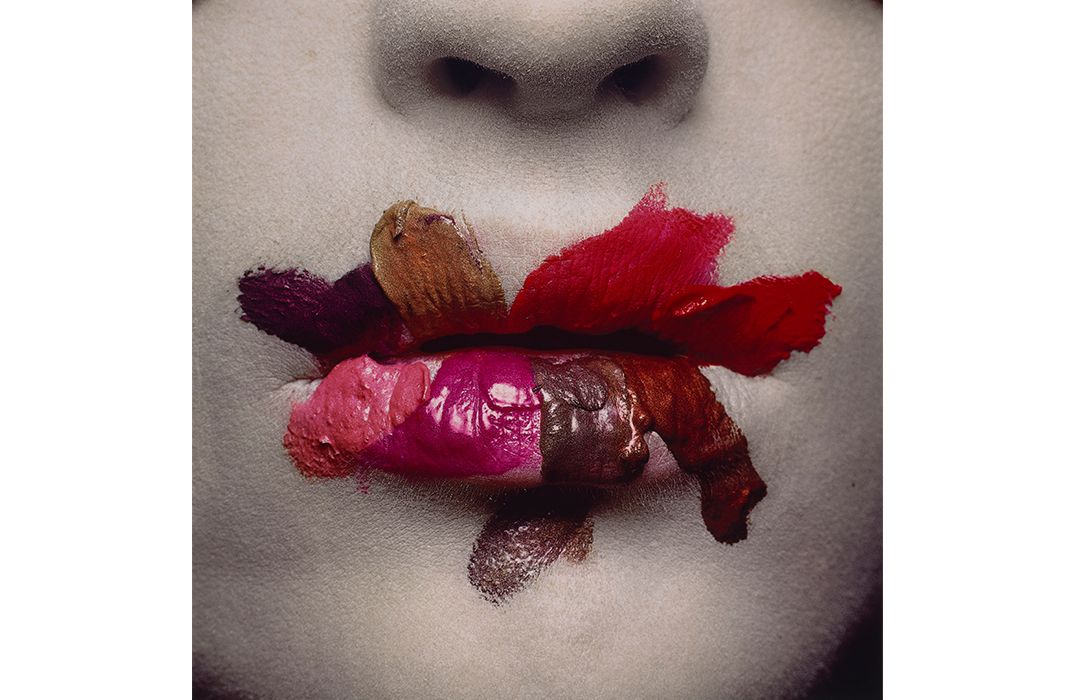

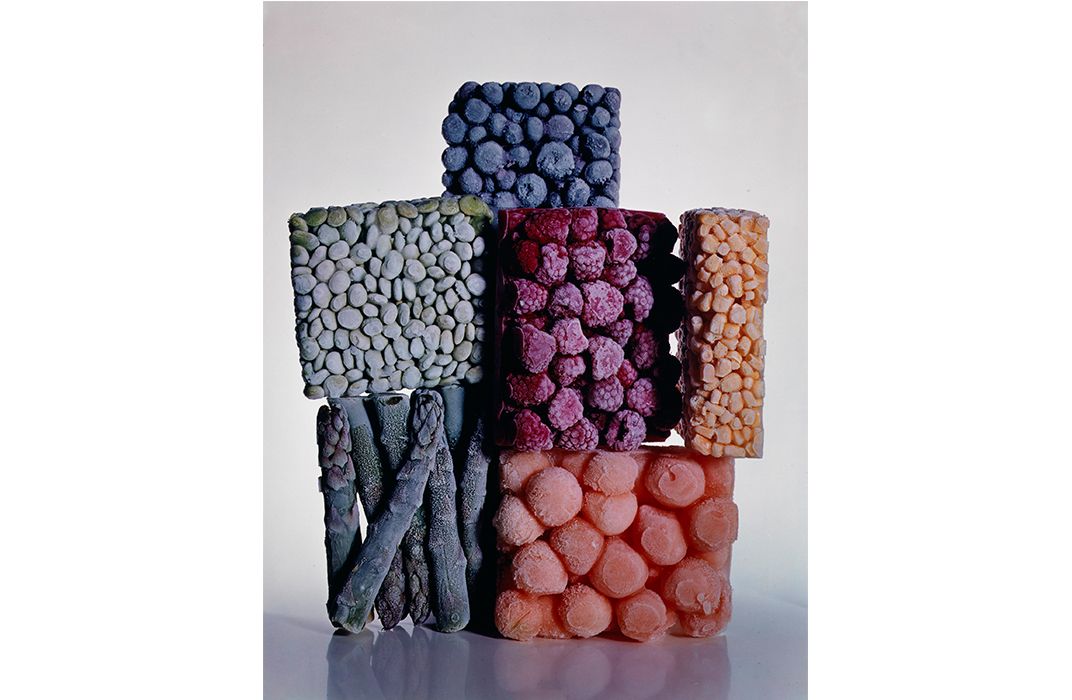

The work revealed the beginning of a personal style—both classical and avant-garde, drawn to odd juxtapositions and beauty in unexpected places.

Penn took a full-time job at Vogue in 1943, then spent the last year of World War II as an ambulance driver and photographer with the American Field Service in Europe, India and China. Some of his restrained images of the fighting’s aftermath were featured in Vogue, and by the time Penn came home his photography had earned a permanent place in its pages.

His first cover, a still-life depicting gloves and a purse, appeared October 1, 1943. His last for the American edition, a portrait of actress Nicole Kidman, would appear in May 2004.

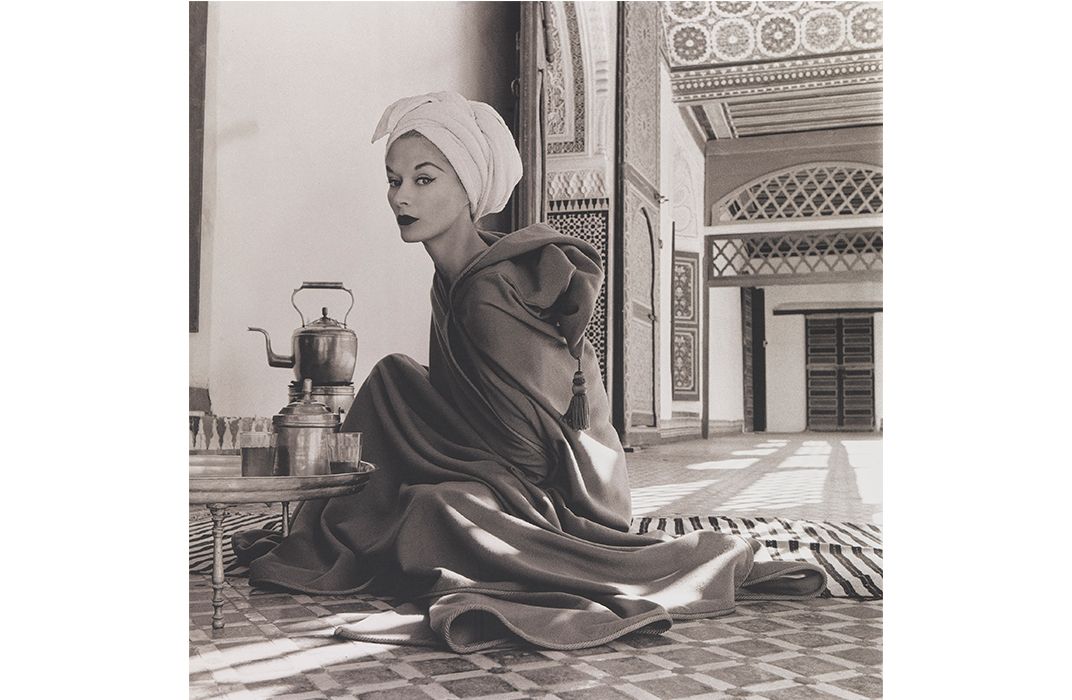

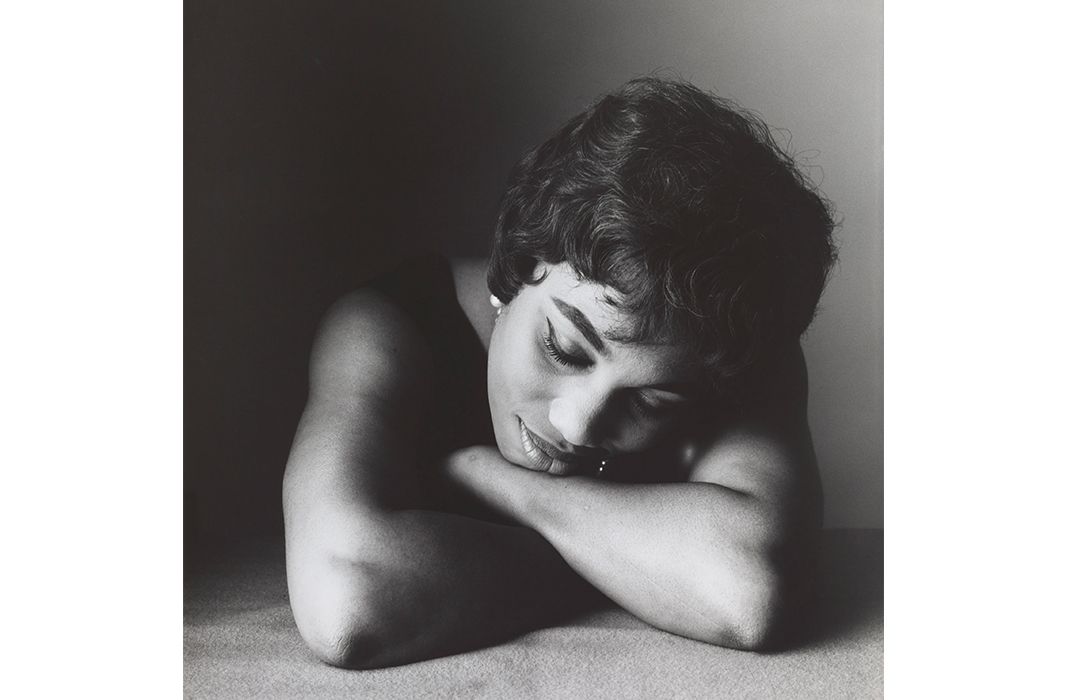

In 1947, Penn was assigned to photograph Lisa Fonssagrives, a Swedish ballet dancer and proto-supermodel six years his senior. Penn and Fonssagrives, who married in 1950, would collaborate throughout the ‘50s, until she retired from modeling and launched a second career as a fashion designer and sculptor.

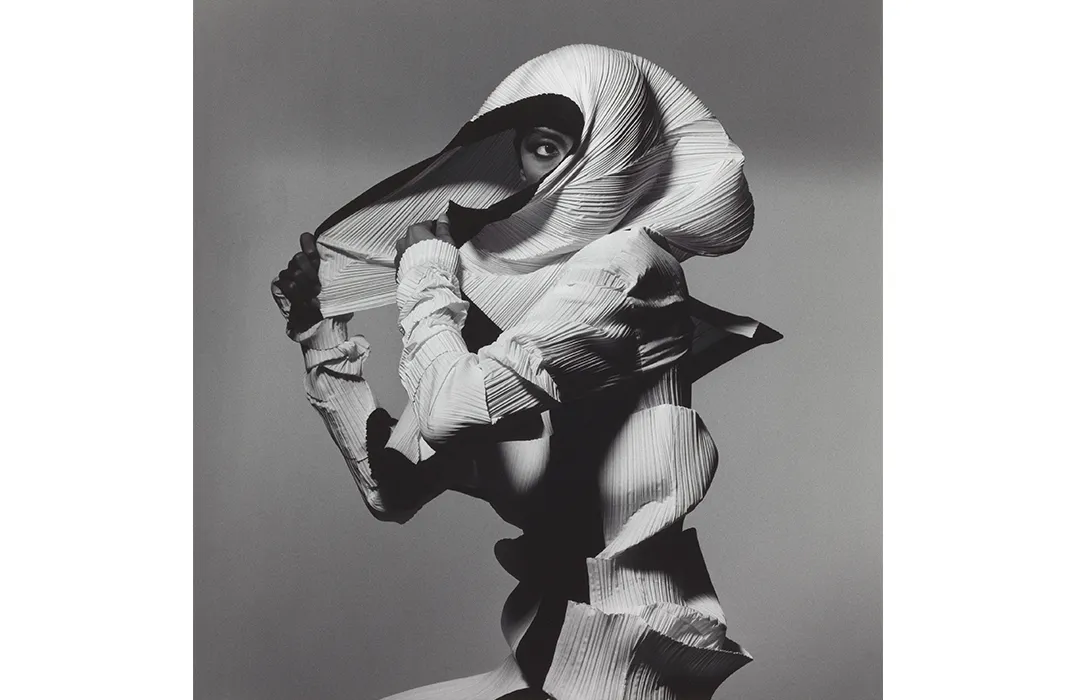

“It was an extraordinary household,” says the couple’s son, Tom. “We shared, at the dinner table, all our thoughts about art. He was always interested in other people’s thoughts and perspectives.” In the evening, Penn would often talk about his day at the studio, speaking of his still-life subjects as if they had personalities of their own, or sharing his enthusiasm over a new couture collection from designer Issey Miyake, with whom he had a long-running collaboration.

Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn died in 1992—an event Penn would refer to for the rest of his life as “the disaster.”

“If you can imagine two extraordinary planets revolving around one another, spinning through the universe, that was very much their existence,” Tom Penn says. “It was wonderful to be part of that solar system. And when my mother passed away, the planets were no longer aligned.”

Penn, who knew that his wife would have wanted him to keep working, threw himself into his work with renewed urgency.

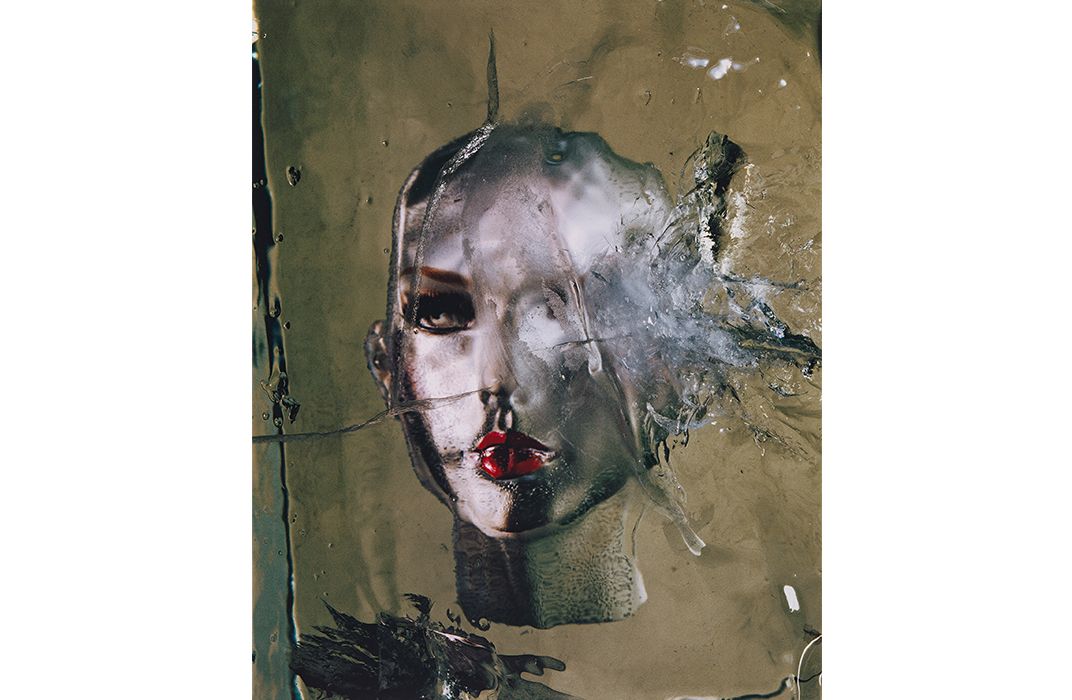

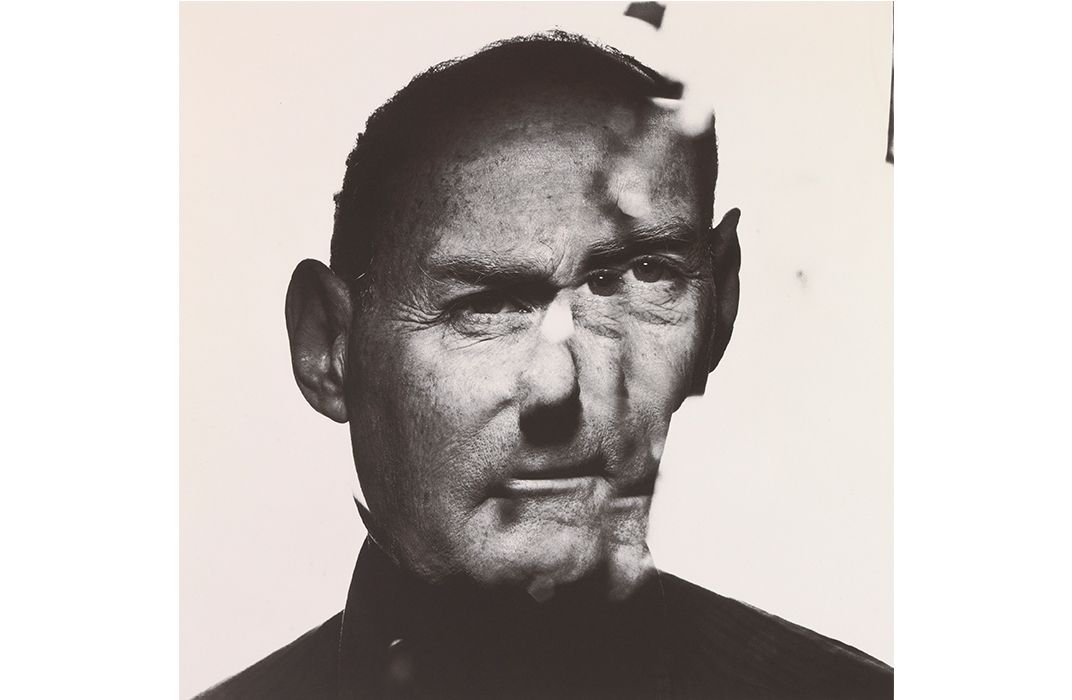

Unlike many artists in their eighth and ninth decades, he continued to experiment, infusing his commissions with new levels of surrealism and pursuing personal projects, like a series of cubist-inspired self-portraits and still lifes of objects from his home, that offered viewers glimpses at Penn’s very private life.

The Hospital

Vasilios Zatse, who was hired as an apprentice in 1996 and worked with Penn until the end of the artist’s life, recalls the Penn studio in those years, at 89 5th Avenue in Manhattan, as “a very serious place.” Outsiders called it “the hospital” because of its clean white walls, and rumor had it Penn and his staff even wore lab coats.

That part was a myth, Zatse says. But Penn indeed ran his studio with lab-like discipline, adhering to a strict nine-to-five schedule, always finishing assignments on time and upholding exacting standards for the quality of his images.

Still, the studio was far from high tech. Penn, Zatse recalls, was happy enough experimenting with 50-year-old cameras and hardware store strobes, and he saw little need to invest in the latest equipment. And while the environment may have been spartan, Penn was never cold.

“Penn was the perfect gentleman,” Zatse remembers. “At the end of the day, he would always make sure to thank us all—the assistants, the model, the hairstylist—for the day’s work. He always referred to them as ‘our pictures.’”

Penn’s humble generosity set him apart from other artists of his stature, and he commanded incredible loyalty from his team.

Zatse continued working for Penn even after his mentor’s death, as associate director of the Irving Penn Foundation (Tom Penn is executive director), which works with museums, galleries and publishers—including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, to which it donated 100 photos in 2013—to promote Penn’s legacy.

Zatse worries sometimes that Penn has no real heir among contemporary photographers, but his influence may be broader than that.

“There is a huge sea-change happening, with so many people taking pictures now,” Foresta says. “And they’ve had their eyes trained by the pages of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar and W. There’s a look that people go for.”

One of the most accessible venues for that look is Instagram, the photo-sharing service released in 2010, the year after Penn died. Tom Penn isn’t sure how his father would have felt about it—selfie culture, he says, is “so contrary to the very fiber of his identity”—but, after wrestling with the idea for some time, the Penn Foundation joined Instagram this year.

“I think that he would understand that Instagram is necessary in our new world,” Tom Penn says. “But I don’t think that he would love the concept, its fugitive nature. His idea of a photograph was something that lived forever.”

That was true for Penn's portraits of glamorous models and famous artists—as well as for his images of street trash.

“Irving Penn: Beyond Beauty” is on view in Washington, D.C. at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through March 20, 2016, before traveling to the Dallas Museum of Art in Texas (April 15-August 14, 2016), Leslie University, College of Art and Design in Cambridge, Massachusetts (September 12-November 13, 2016), the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, Tennessee (February 24, 2017-May 29, 2017) and the Witchita Art Museum in Kansas (September 30, 2017-January 7, 2018)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/cf/82cfb643-0325-41e9-9f99-4297aa407047/pennbeautyshopweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/cc/0dcc1ade-ee37-4800-af45-38be806700d7/penngirlbehindbottleweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9e/7f/9e7f1271-7346-4e58-afc9-c91e4411a08e/penndaliweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8b/a0/8ba037cf-cfdf-4b24-a9c3-ed5443ab9dd0/penncapoteweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/89/70/8970e618-46e4-4936-8da9-645cd15a763c/pennballdressweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)