How One Artist Learned to Sculpt the Wind

Artist Janet Echelman studied ancient craft, travel the world and now collaborates with a team of specialists to choreograph the movement of air

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/ea/f5ea9962-9d78-406c-8e26-4c1df4fa27a6/echelman184web.jpg)

“I am starting to list the sky as one of my materials,” says sculptor Janet Echelman who produces aerial, net-like sculptures that are suspended in urban airspaces.

Her pieces, created from high-tech fiber developed originally for NASA spacesuits, are described as “living and breathing” because they billow and change shape in the wind. During the day, they cast shadows and at night, they are transformed by computer-controlled lights into “luminous, glowing beacons of color.”

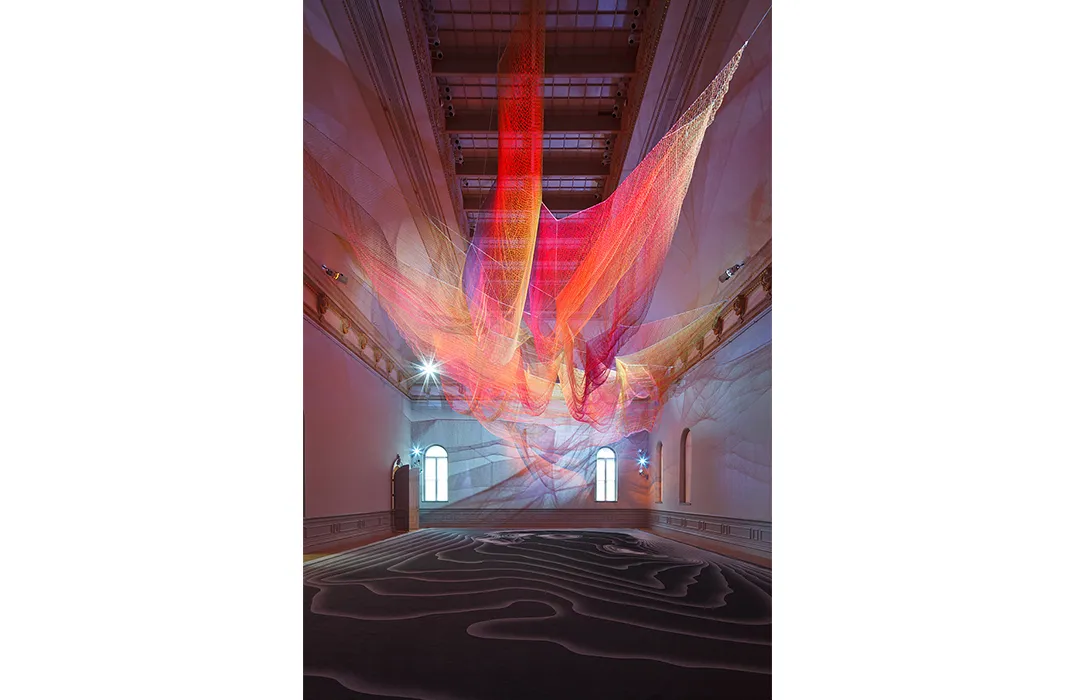

Echelman is one of nine leading contemporary artists commissioned to create installations for the inaugural exhibition titled "Wonder" at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

For the Renwick’s historic Grand Salon, Echelman created an immersive piece, called 1.8, that incorporates her first ever textile carpet, made of regenerated nylon fibers from old fishing nets, as well as a hand-knotted rope and twine sculpture suspended from the ceiling.

“I wanted the visitor to be within the work,” she says with a faint southern lilt that hints at her Florida roots. Seating is sprinkled throughout the gallery to enable visitors to observe the swelling and surging of the net, which will be caused by artificial wind gusts manufactured by Echelman’s creative team.

“Outside, it’s very much about responding to the environment, but for this exhibit we get to sculpt the air currents to choreograph the movement,” she explains.

According to Echelman, her sculpture is inspired by data supplied by NASA and NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, measuring the effects of the earthquake and tsunami that ravaged Tohoku, Japan in 2011. The shape of the net is based on a 3D image of the tsunami’s force created by Echelman’s team.

“The piece aims to show how interconnected our world is, when one element moves, every other element is affected,” she says.

Echelman has been widely recognized for her innovative art form. She won a Guggenheim fellowship for exceptional creative ability, received a Smithsonian American Ingenuity award, and gave a TED-talk in 2011 that has garnered nearly 1.5 million views.

Visual art, however, was not Echelman’s first passion. She grew up playing the piano and attending summer camp at the Tanglewood Institute, a pre-professional program associated with the Boston Symphony orchestra. She also won a prestigious regional competition that earned her a coveted soloist spot with the Florida Orchestra.

“Music taught me the patience to take things apart and improve each component, but for my professional day job, I like a blank canvas rather than the job of reinterpreting someone else’s work,” she explains.

While an undergraduate at Harvard, she took her first visual art classes; and one assignment—to write about an artist’s entire body of work—unwittingly set her on her current path. She wrote about Henri Matisse and traced his trajectory from painting to the paper cutouts he developed at the end of his life when he was wheelchair bound.

“That’s the way I want to live. I want to be responsible for defining my medium,” Echelman remembered thinking.

Following college, she was applied to seven art schools and was rejected by all of them, so she decided to move to Bali to become a painter on her own. Echelman had lived in Indonesia briefly during a junior-year abroad program, and she wanted to collaborate with local artisans to combine traditional Batik textile methods with contemporary painting.

Echelman says that her parents had differing opinions of her unorthodox plan. “My father, an endocrinologist, asked whether any of my college professors had told me that I had talent and should pursue art. The answer was no,” she admits. “But my mom, a metal smith and jewelry designer, thought it was a fine thing to want to do and gave me $200 to buy supplies,” she recalls.

“It wasn’t that I had the goal to become an artist, but I wanted to be involved in the making of art everyday,” says Echelman.

For the next ten years, Echehlman painted and studied various forms of high art and artisanal crafts through a mix of fellowships, grants and teaching jobs. Along the way, she managed to earn an MFA in Visual Arts from Bard College and a Masters in Psychology from Lesley University.

“My system was to go and learn craft methods passed down from generation to generation,” she explains. She sought out opportunities to study Chinese calligraphy and brush painting in Hong Kong, lace making in Lithuania, and Buddhist garden design in Japan.

Immortalized in her TED talk is the story of how she first hit upon the idea of creating volumetric sculpture out of fishing nets. Echelman was on a Fulbright Lectureship in India in 1997 where she planned to teach painting and exhibit her work. The paints that she sent from America failed to arrive, and while searching for something else to work with, she noticed the fishermen bundling their nets at the water’s edge.

Nearly two decades after those first fish net sculptures, known as the Bellbottom Series, Echelman has created scores of artworks that have flown over urban spaces on four continents. Her first permanent outdoor sculpture was installed over a traffic circle in Porto, Portugal in 2005. The work, called She changes consists of a one-ton net suspended from a 20-ton steel ring. Only five years later, high tech materials had developed so quickly that she could now attach her sculptures to building facades without the need for the heavy steel ring support.

Maintaining her permanent sculptures is serious business. These pieces, which float over such cities as Seattle, Washington, Phoenix, Arizona, and Richmond, British Columbia, undergo regular maintenance protocols to ensure they are safely airborne. Protecting wildlife is also a priority for Echelman. The artist’s website maintains that her sculptures do not harm birds because her nets are made of thicker ropes with wider openings than those used to trap birds.

For each new work, Echelman consults with a cadre of architects, aeronautical engineers, lighting designers and computer programmers throughout the world.

“I don’t have a deep knowledge of all these disciplines. But I consider myself a collaborator,” she says. “I have an idea, a vision and we work together to realize it,” she continues.

Echelman also gratefully acknowledges that she has realized the twin goals she set for herself as a fresh-faced undergraduate in an earlier century. She has succeeded in defining her own medium and she is happily involved in the making of art every day.

Janet Echelman is one of nine contemporary artists featured in the exhibition “Wonder,” on view November 13, 2015 through July 10, 2016, at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. Echelman's installation closes on May 8, 2016.

Wonder

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Lucy_Harvey_151120_1745_WEB.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Lucy_Harvey_151120_1745_WEB.jpg)