A Look at the Creative Process and What Makes an Artist Tick

A new exhibition delivers a better understanding of where artists find their inspiration

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b1/4e/b14eae75-4713-439d-9179-d4a37b5437ee/aaa_arnoanne_61128-wr.jpg)

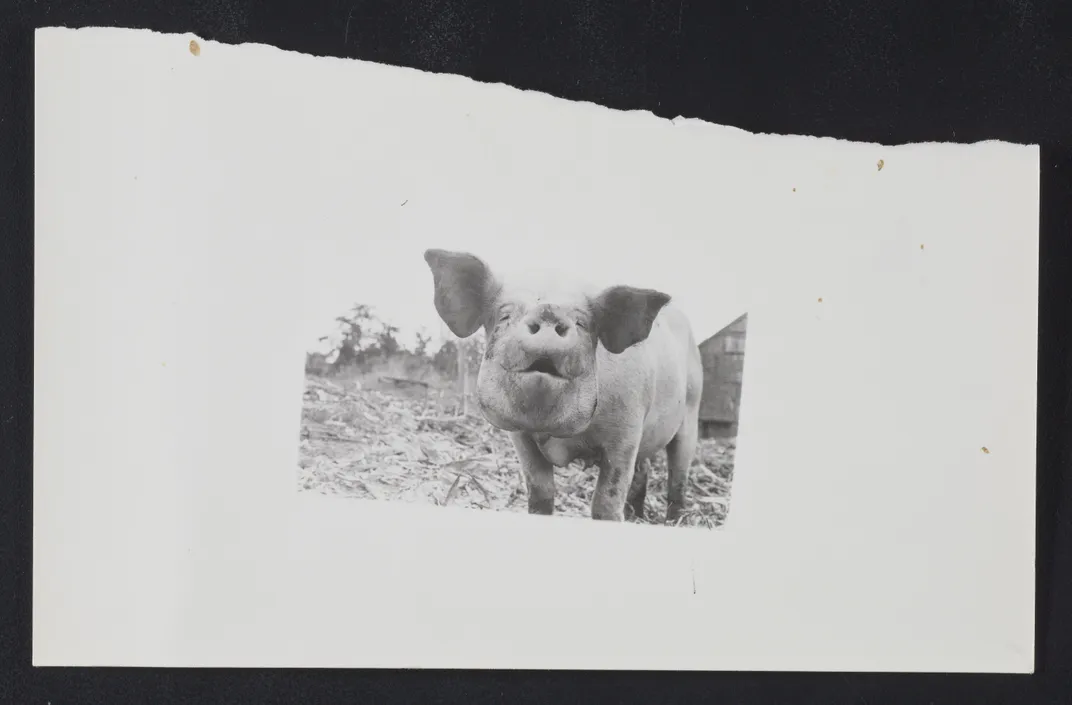

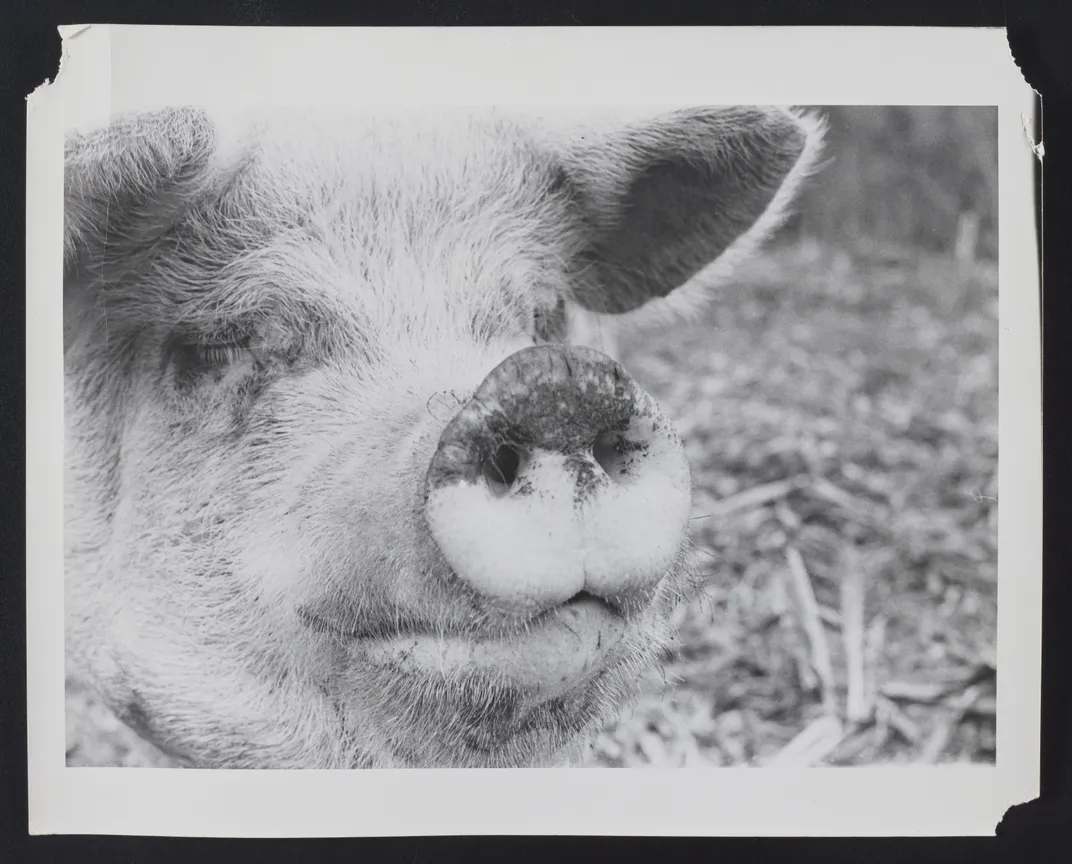

The upturned snout, snotty, sarcastic expression and defiant stance of sculptor Anne Arnold’s Wall Pig, speak volumes about the artist’s ability to imbue her work with the character of the animals that were her beloved subjects. Arnolds, a sculptor and educator, died in 2014.

The emotion that radiates from the sculpture is reminiscent of how Wilbur from Charlotte’s Web must have felt, when his spider friend described him as “Some Pig” in an effort to save him from slaughter. It also shows the depth of an artist’s connection with her source material—from which her final works were created.

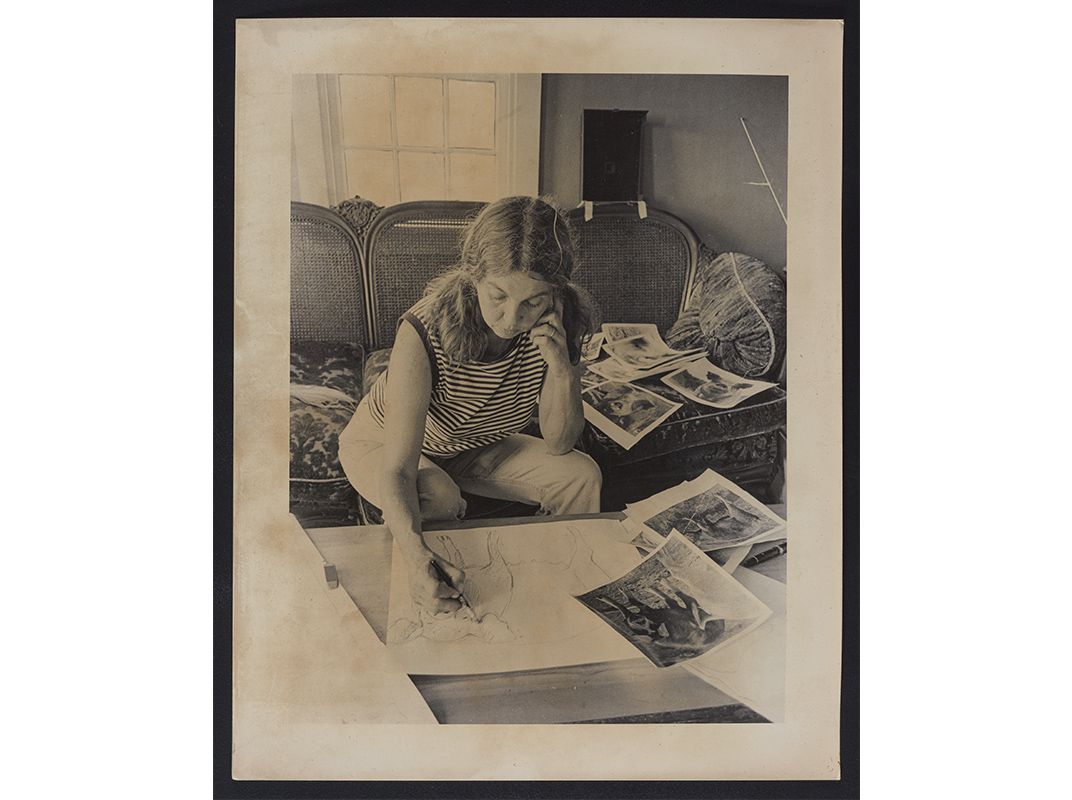

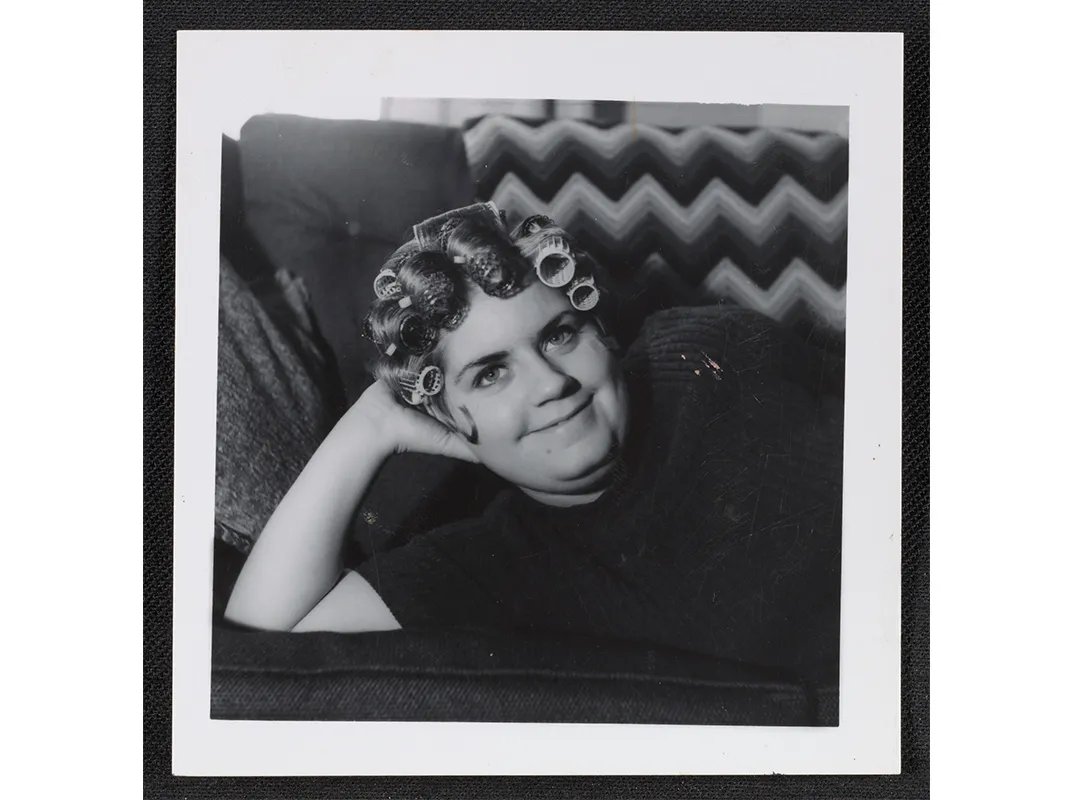

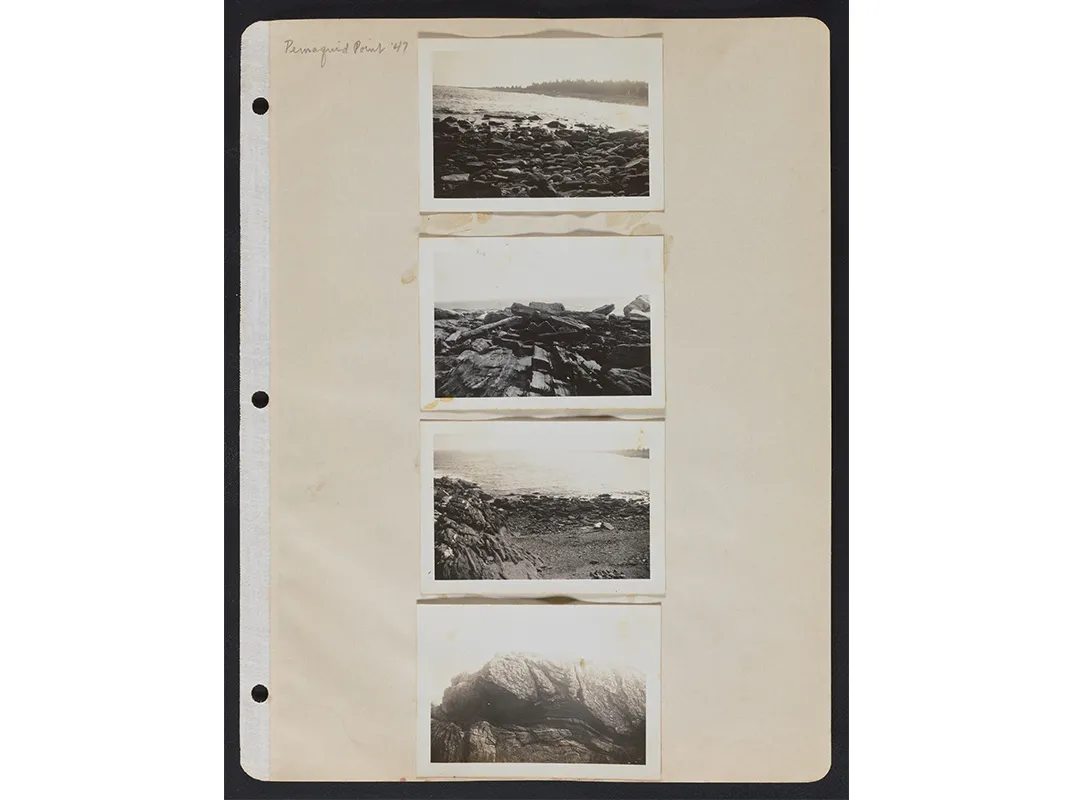

“She really got the character of this pig!” says Mary Savig, curator of manuscripts for the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art. Savig put together the exhibition, “Finding: Source Material in the Archives of American Art,” which examines the way that different artists use source material as inspiration for their creations. The show includes Arnold’s 1971 sculpture, Wall Pig, along with a photograph of the artist drawing a picture of the clearly contrary porker, from photos she had taken of the creature.

“She was an artist who lived in Maine on this farm, so she did have a lot of animals surrounding her,” Savig says. “She would photograph them, and she also received commissions from other people who wanted sculptures of animals. . . She worked in 3D in metal and wood, so she would take many different angles of the pig, so when she went to draw it and then make the sculpture she would have every angle. . . . That was really helpful to her as an aide in her process.”

Arnold also did a lot of cat sculptures, and some goats as well. She bought the farmhouse where she lived with her husband, abstract painter Ernest Briggs, in 1961 in Montville, Maine, and summered there for decades.

“As a child, I was fortunate to be able to spend long summers in the wood, and on the sea—to have had time to watch plants grow and birds build nests, and to have known and loved many animals,” Arnold said in a 1981 interview with Gazette magazine. “I learned much from those animals and grew to respect the specialized abilities of each and to understand the meaning of the web of life long before I had heard the word ecology. The animals also taught me that there is a form of communication that doesn’t involve the use of language. This sense has stayed with me as an adult, and I hope inhabits the sculpture as well.”

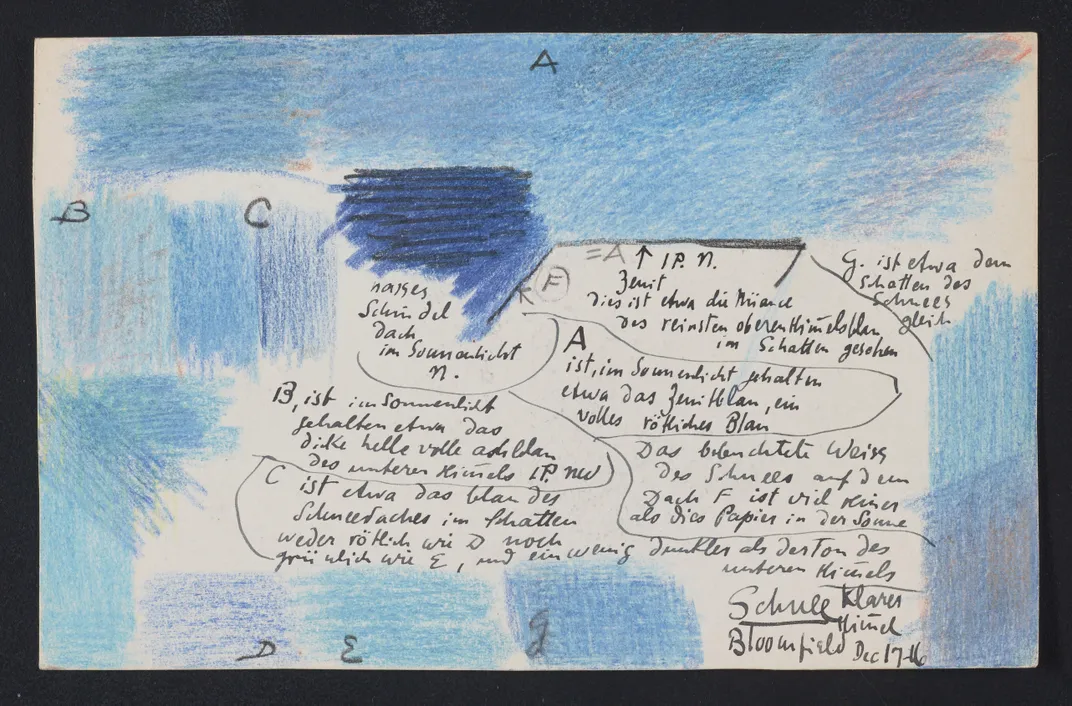

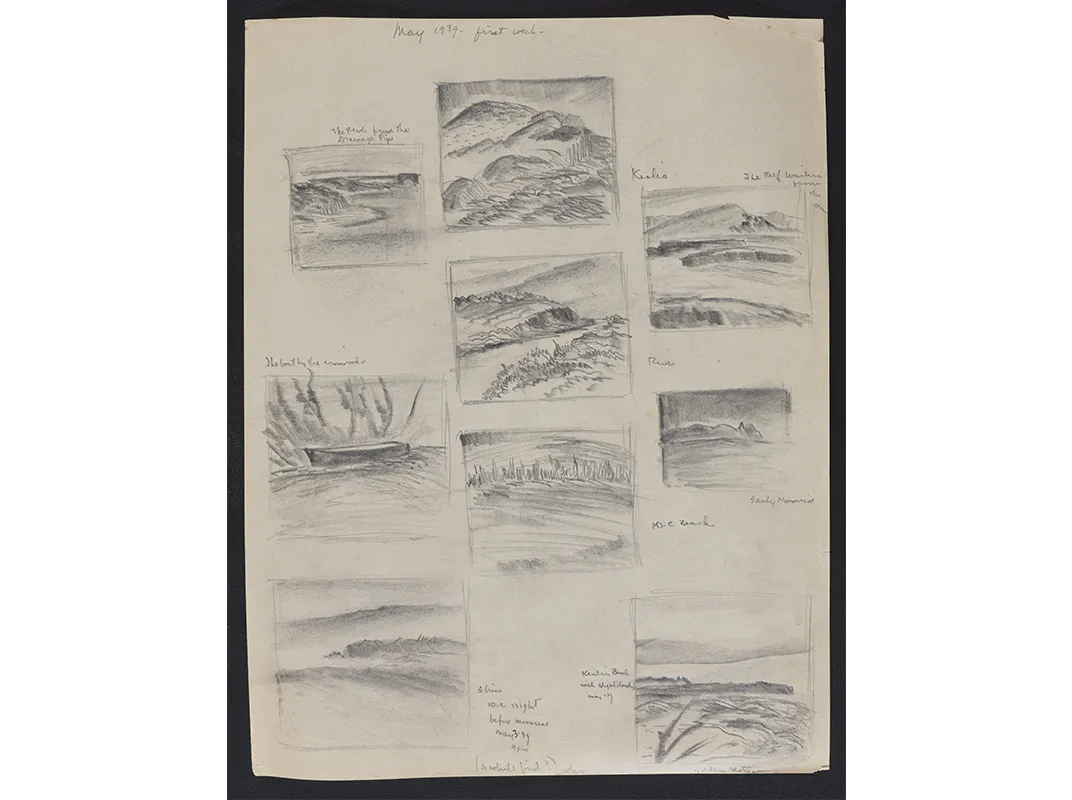

Savig says the goal of this exhibition was to show the different ways artists use source material. Some, she says, collect it and use it as ways to evoke ideas. They might look at a landscape as source material, and then create something totally different like an abstract painting.

“With these exhibitions, we’re trying to show that a lot of thought went into it,” Savig says, “not just physically making the work, but planning for a piece. Even coming up with the idea and finding the source of inspiration for a piece is a big part of the artistic process, and often we can trace that back to some sort of source through our archival material.”

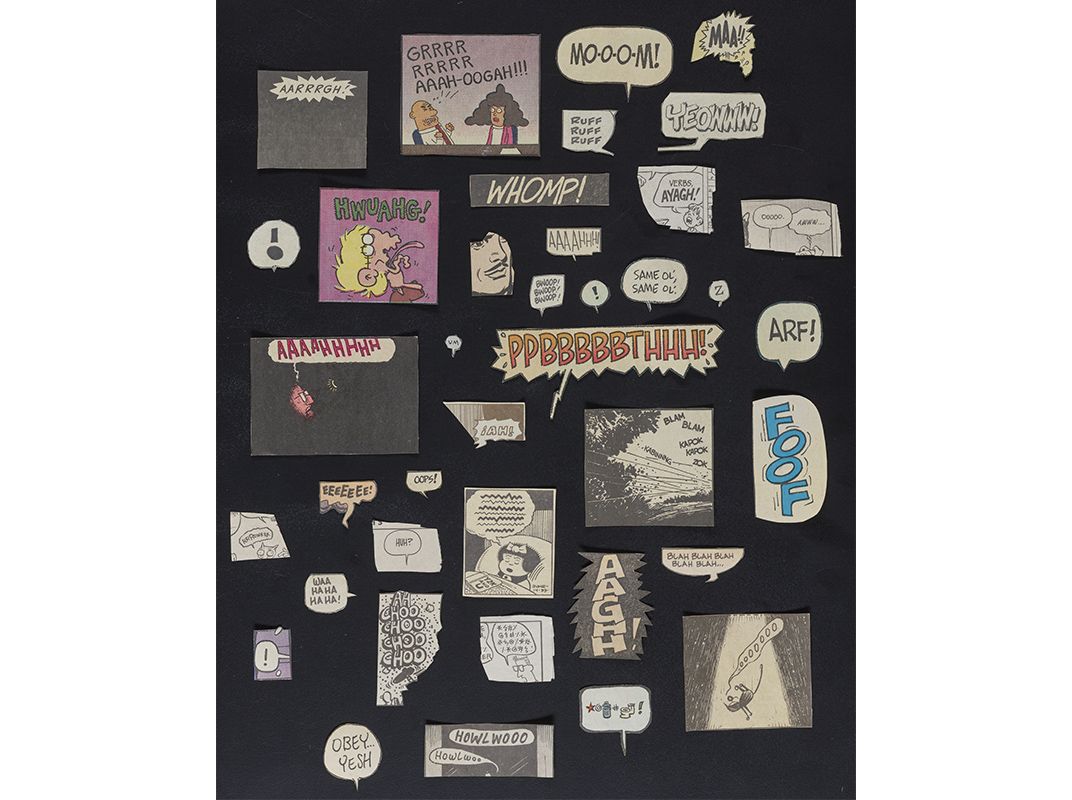

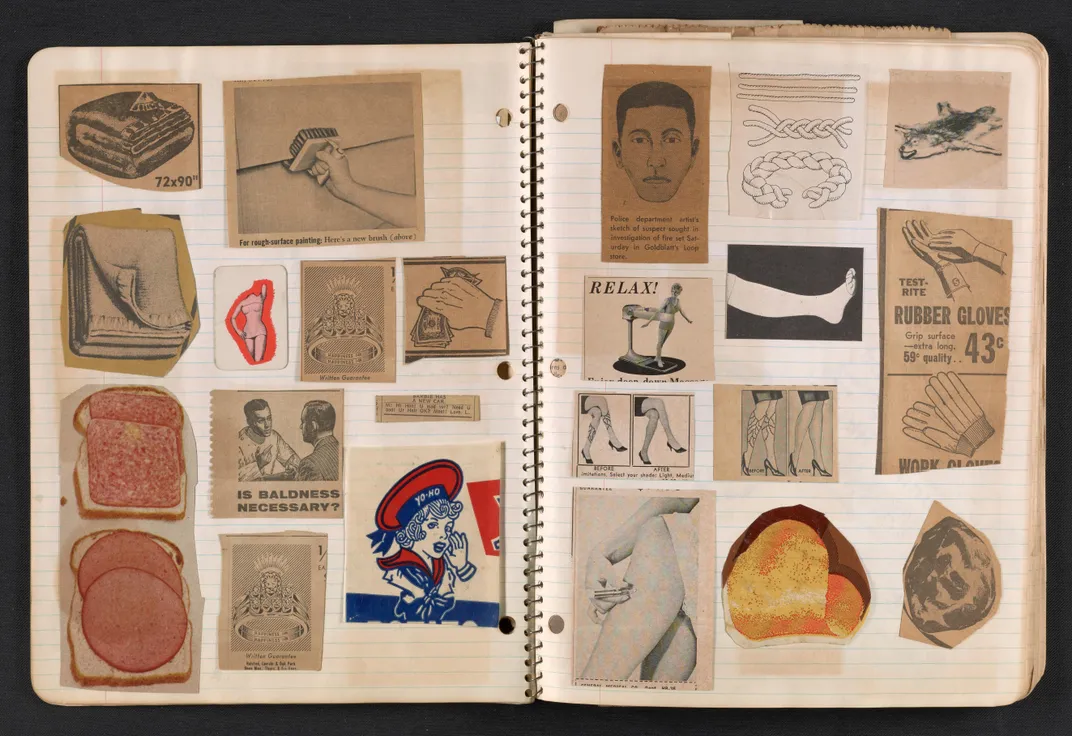

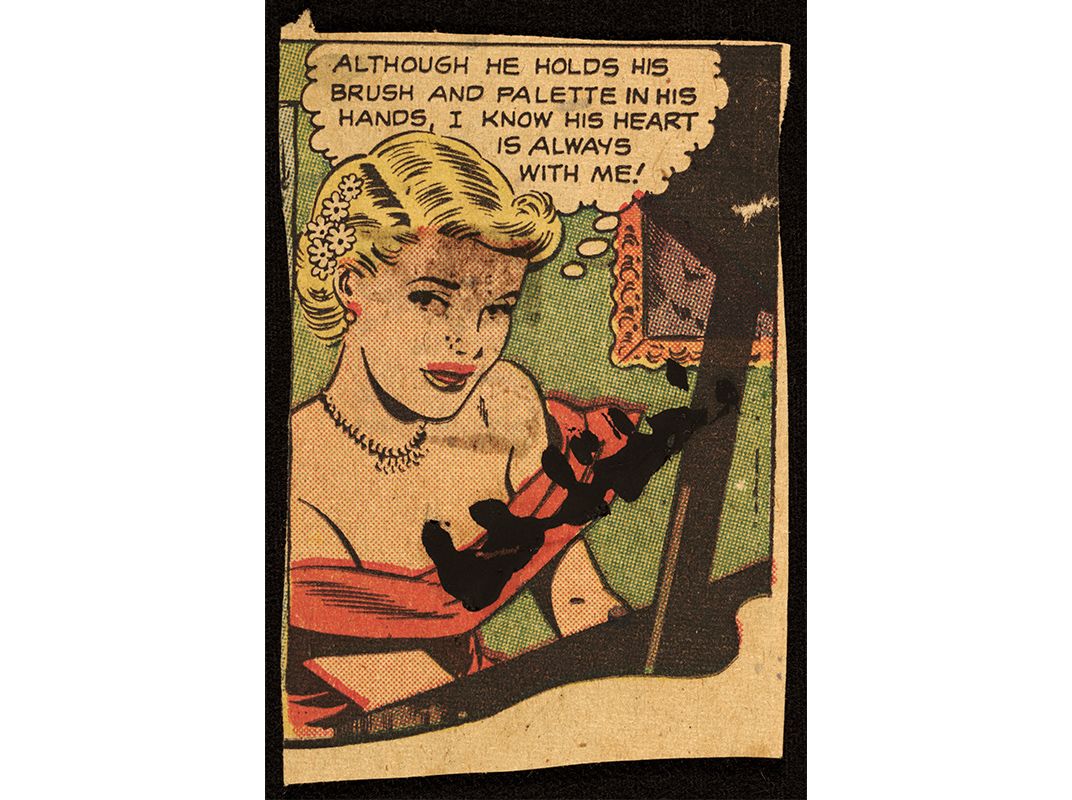

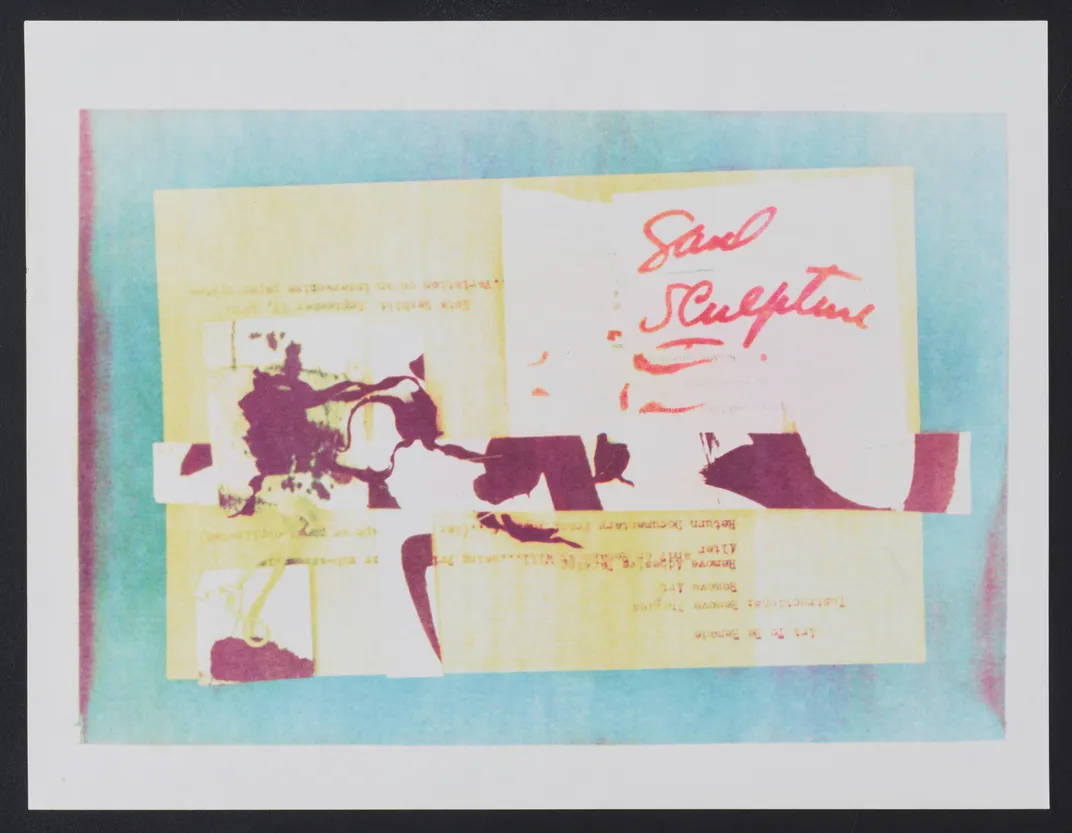

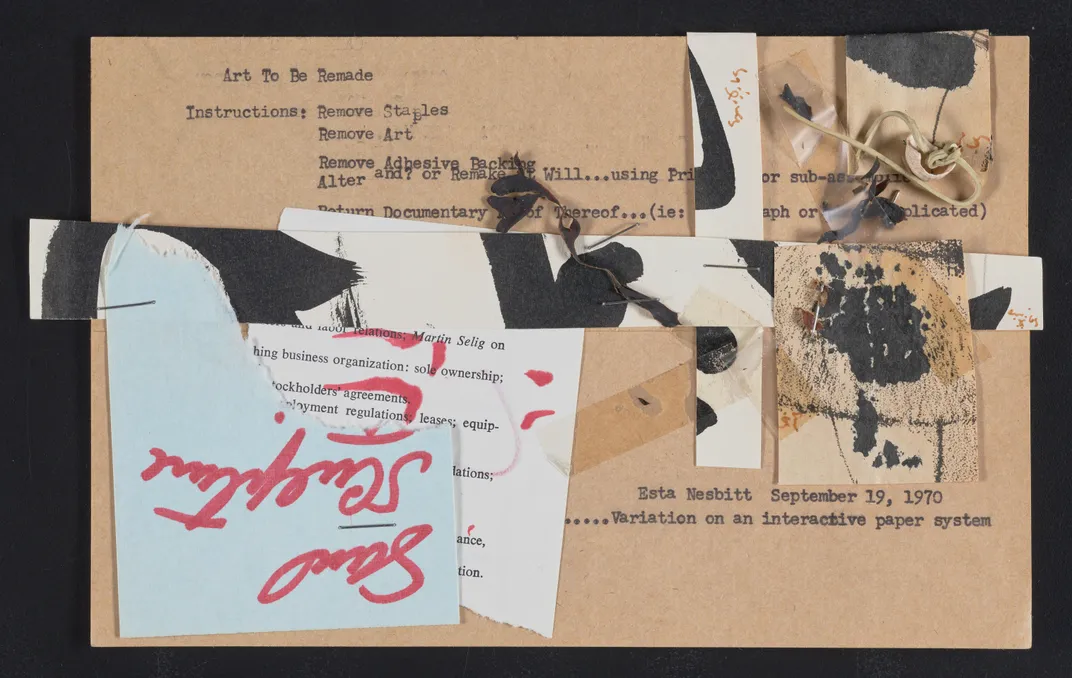

The Archives of American Art is a research center that collects the papers of American artists—including gallery records, artists’ papers, love letters and diaries. It mounts three or four exhibitions a year. Some of the material is whimsical, such as the gargantuan amount of source material collected by Chicago collage and semi-abstract artist Ray Yoshida (1930-2009). One of the best known contributors to a tradition known as Chicago Imagism or the Chicago school, Yoshida’s work featured everything from bits of comics to pictures from popular magazines.

“He was really attracted to the specific shape of things,” Savig says. “He would clip these little things out from comic books and comic strips to trade magazines like a plumbing book. He would cut out pictures of plumbing, and the pipes, and then he would paste it into these books, or he would just save it in these Sucrets boxes.”

Huge images of Yoshida’s source material, including bits from the comic strips Cathy, and Mutts, adorn the walls of the tiny room where the exhibition is mounted, with glass covered tables strewn with the material that inspired the featured artists including Yoshida. They include images of slices of pizza, tires, pictures of steaks and entire books of comics, some showing people kissing, others of hands punching someone out.

“Here’s an entire envelope of words, he did figures, some of eyes and mouths,” Savig notes. “He was just a really voracious collector, and we have a lot of this material and it’s really interesting because you can see the beginning of his art work, and the beginning of his process.”

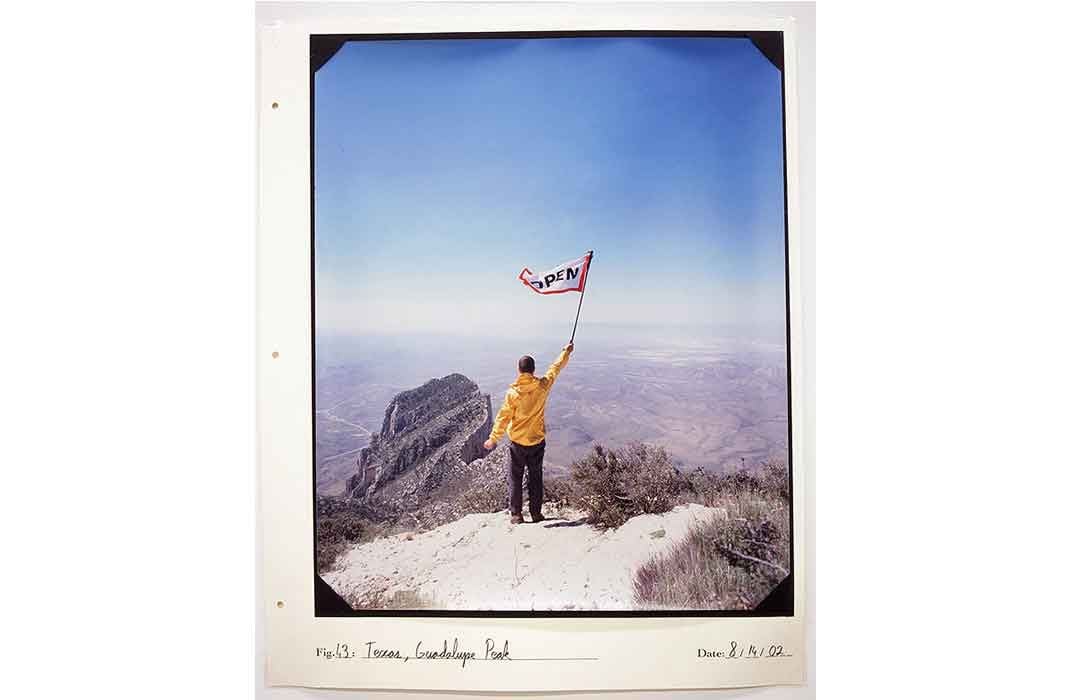

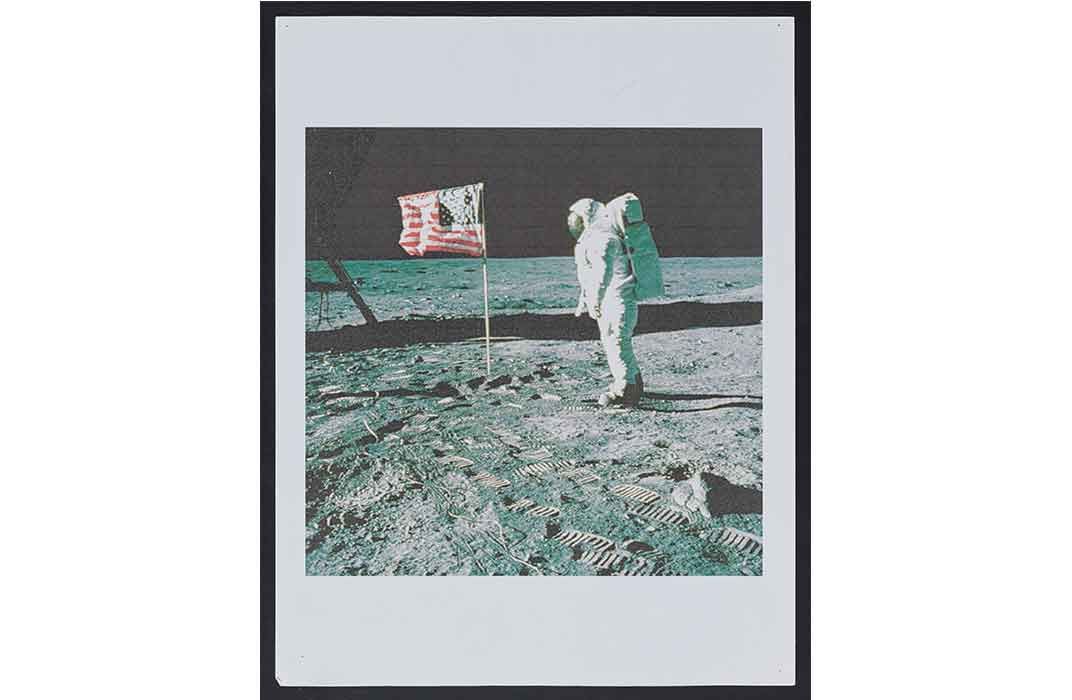

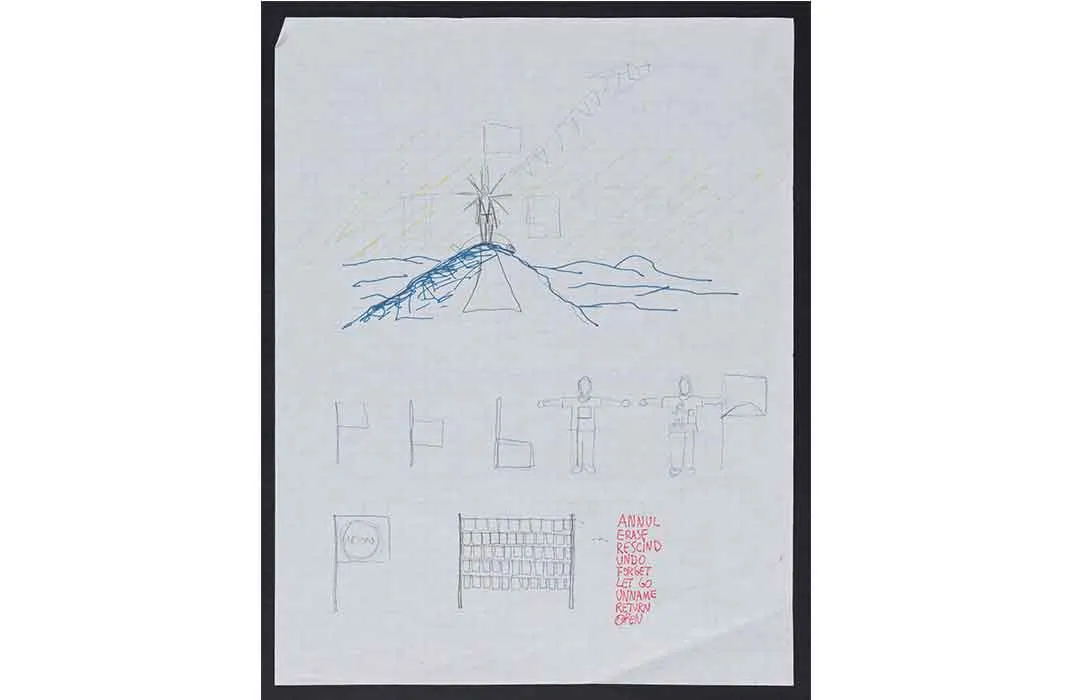

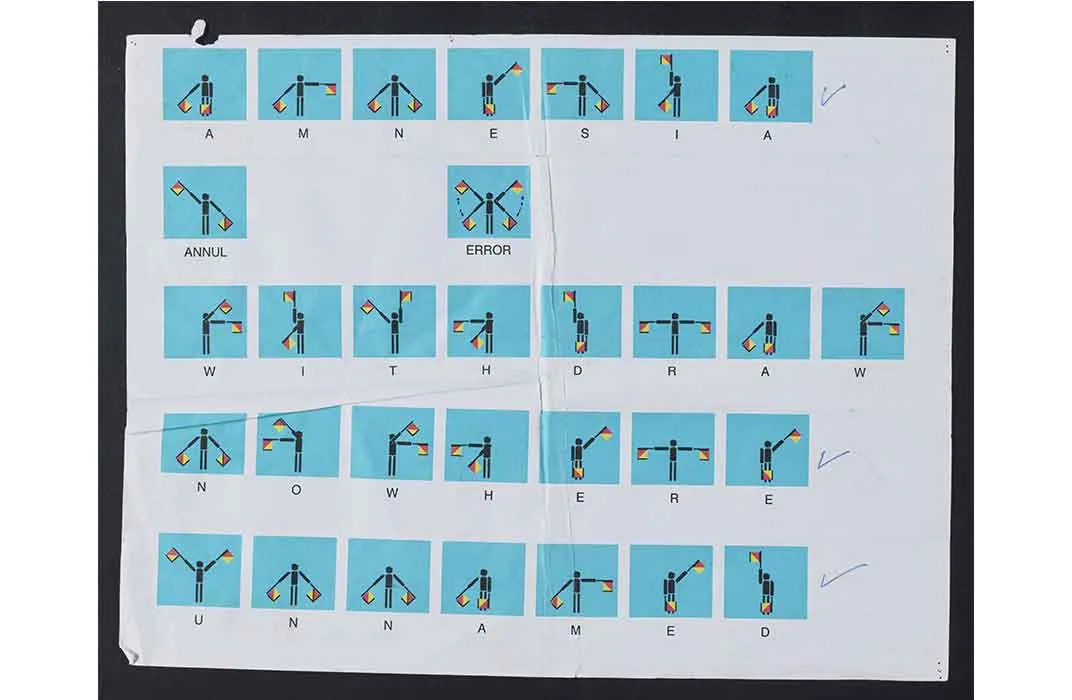

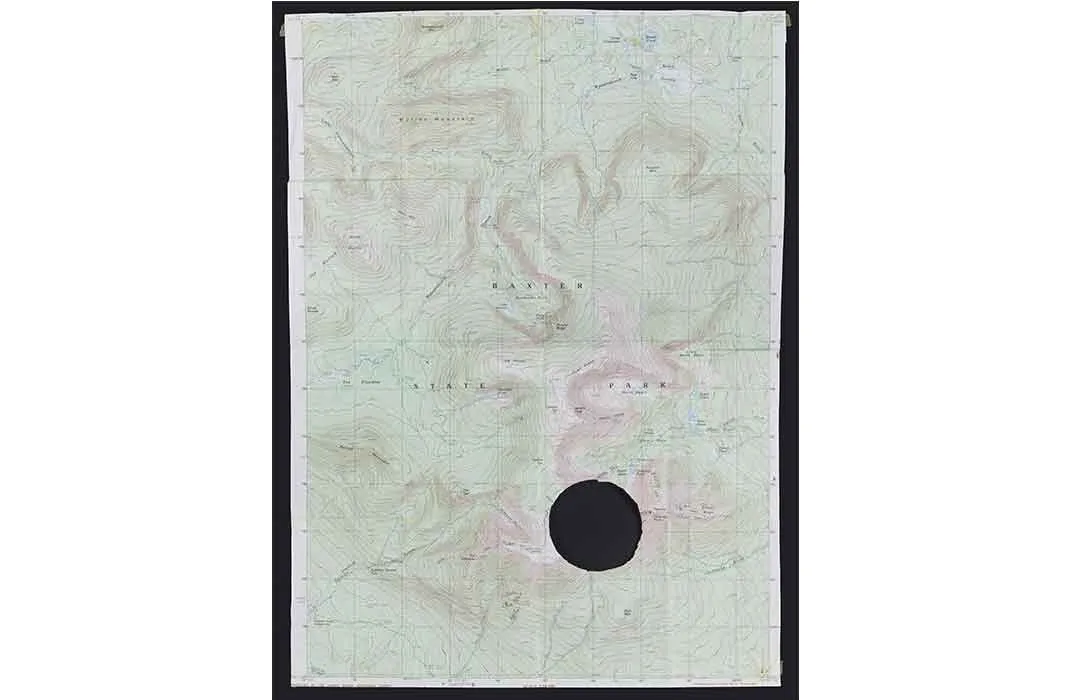

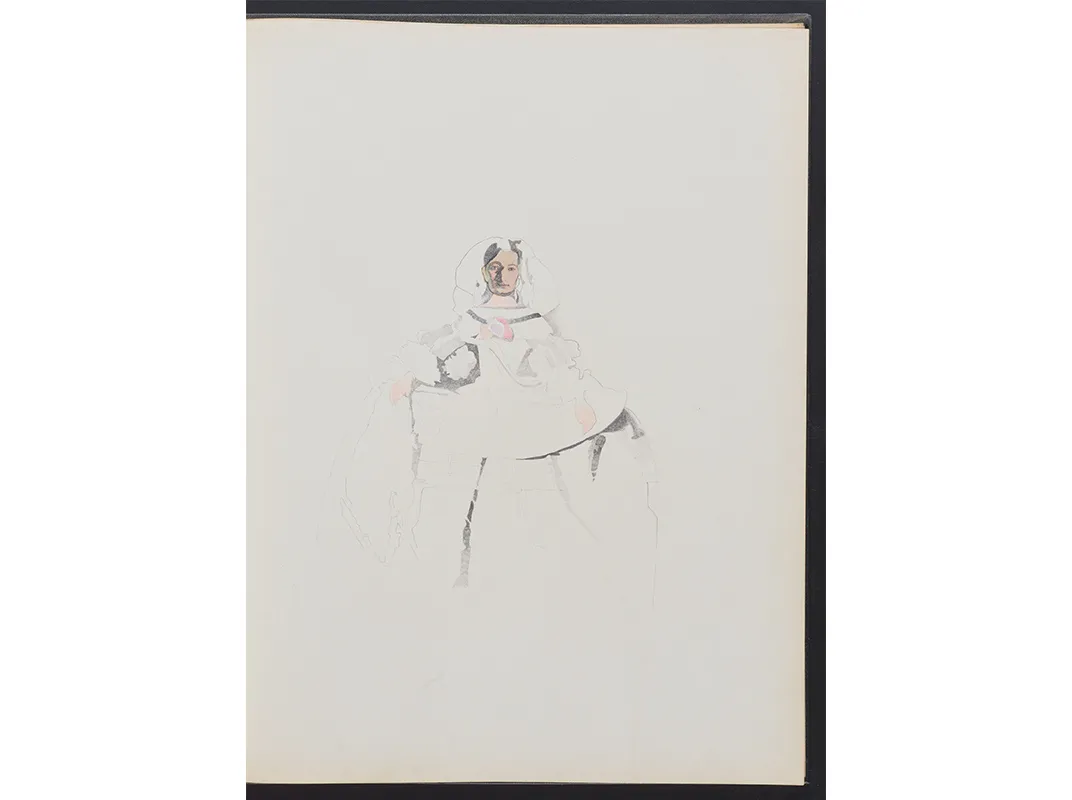

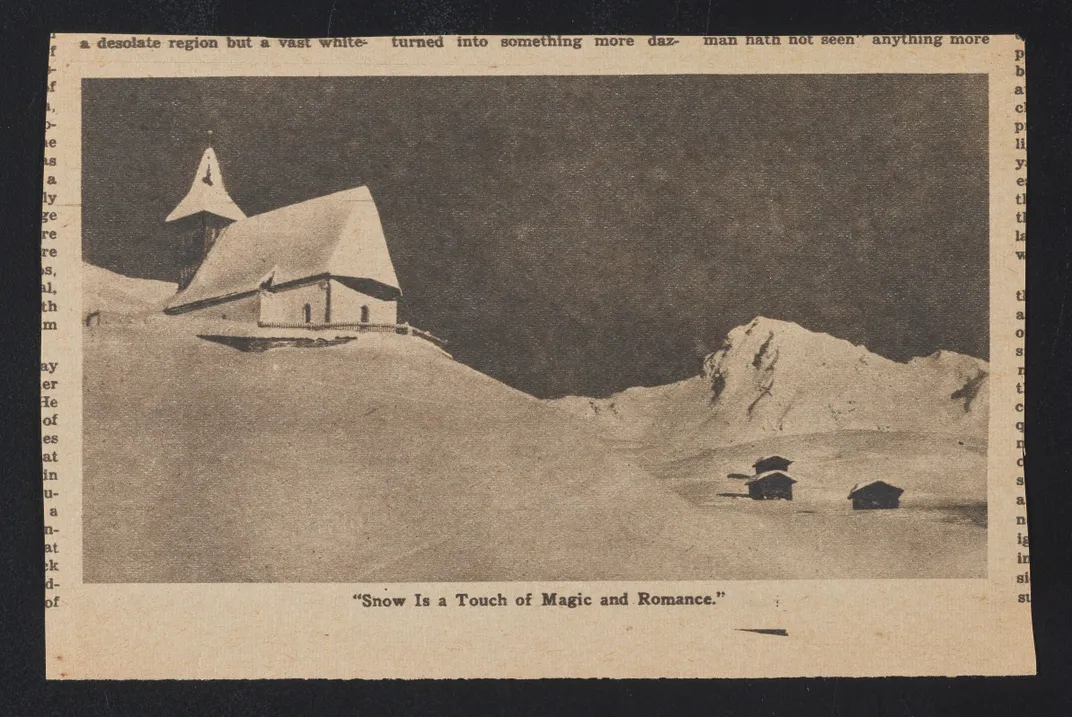

Paul Ramírez Jonas, born in California in 1965, also contributed source material for this exhibition, from his on-going project Album: 50 State Summits. In 2002, he began a quest to scale the highest peak of every state in the nation. His source material includes a photograph of Astronaut Buzz Aldrin walking on the moon in 1969, and another of mountaineer Edmund Hillary, the first person to climb Mount Everest along with a Sherpa guide. There’s also the semaphore flag alphabet.

Ramírez Jonas says he began the project by thinking about discovery that is geographic. He had read the diaries of Lewis and Clark, and studied the Columbus expedition, and noted that explorers often believe they will be the first to get somewhere, then realize there are already people there. So Ramírez Jonas had an idea of climbing the highest mountains, and giving them names because he would be that proverbial first person.

“If you buy a kit to assemble a kite and fly it, we know exactly what will happen, but it doesn’t preclude us from having an incredible surge of feeling and emotion. It doesn’t matter that everyone else has done it,” Ramírez Jonas explains. “So I started to think about discovery that’s geographic. The entire planet has been explored … and yet we continue to do it and it continues to mean something to us.”

In addition to visiting the 50 sites, Ramírez Jonas says he decided to add three more destinations to his project: the furthest you can get from the center of the Earth, the furthest you can get from home, and a mission to climb something on the 50th anniversary of the first ascent of Mount Everest.

“There’s a volcano near the equator in Ecuador called Chimborazo. If you measure from the center of the Earth to the top of that it is higher than Everest,” Ramírez Jonas says. And for the 50th anniversary of the ascent of Everest, he says he climbed a salt mountain off of New York City’s West Side Highway.

Ramírez Jonas says the source material he gave to the Smithsonian, for him, were research materials that enabled him to work on his still unfinished project, map his directions, and think through his focus. Originally, he says he planned to erase the names of the places he visited, as kind of a reverse conquest, but he says the idea wasn’t communicating visually. So now, after much thought, when he reaches the summit, he flies flags, bearing only the word "Open," and makes a self-portrait of the moment.

“You know when you’re driving on a country road; the sign says ‘open’ ... so I changed that a little bit. (The flag) says ‘open,’ open for business, or ‘this is open space,’” Ramírez Jonas explains. He says he has a specific message he hopes people get from his work. “Hopefully people will think about what it means to discover or have an adventure, what it means to be heroic, what is it to discover something. … I’m always giving my back to the camera. I want it to be that you think you could be me. … That would make me happy.”

Savig says even modern artists use source material, in very similar ways to those featured in the exhibition.

“There’s an artist, Dina Kelberman, who organizes in the same way Yoshida does, but she does it through the internet, so it looks the way Google images look . . . but she does it by type, like landscapes,” Savig says. “There are a lot of people who are still categorizing in a way that makes sense to them, and is common among artists who are trying to work thematically. . . . I’ve been talking to people who still go through magazines and still try to find things that are physical in the world around them, but also things like social media and Instagram! Those are really fantastic sources for a lot of artists.”

“Finding: Source Material in the Archives of American Art,” is on view through August 21 in the Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery, located on the first floor of the Smithsonian's Donald W. Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture, home to the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)