There’s a 1,500-Year-Old Farming Village Beneath a Norwegian Airport

An airport expansion gives archaeologists the chance to dig for historical treasures in a pre-Viking settlement

Archaeologists love construction when it’s done correctly. Moving large amounts of dirt is exactly what these experts need to gain access to the resources buried beneath. That’s exactly what has happened during the expansion of an airport in Norway.

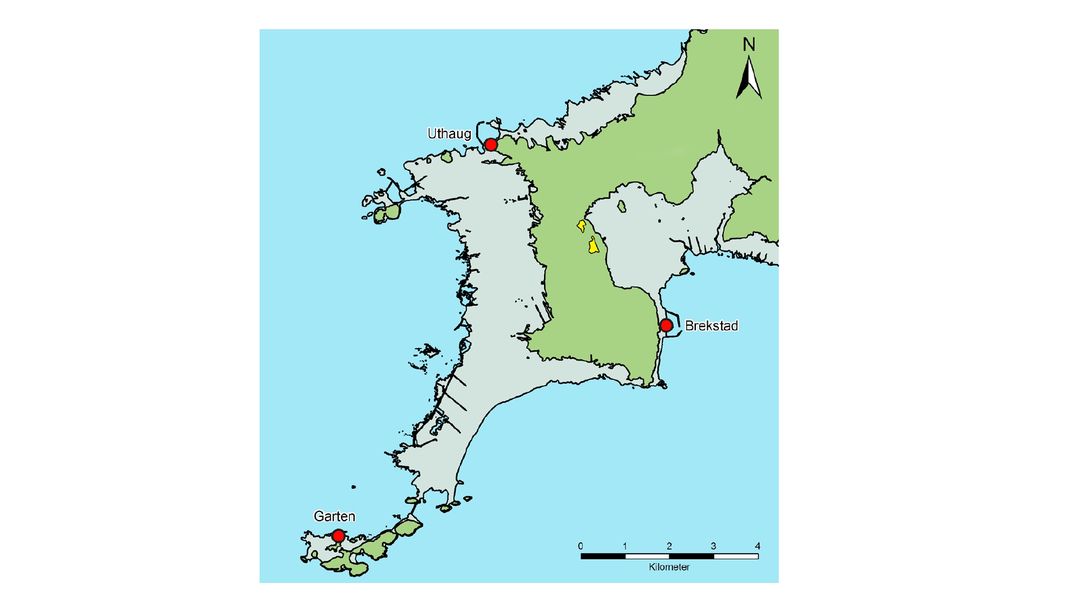

Ørland Airport is built on a seahorse-head-shaped peninsula that juts out into the Norwegian sea, but that land once looked more like a hooked finger, with a sheltered bay on its southern side. That led a community of Iron Age farmers to build a settlement in its shelter, reports Annalee Newitz for Ars Technica. Experts have long known of the once wealthy community in that bay that sprang up 1,500 years ago, before the Age of Vikings. But a dig is expensive, so they bided their time.

But, when the airport decided to expand—after purchasing 52 new F-35 fighter jets—archaeologists knew they’d find something good, writes Nancy Bazilchuk for Gemini, a publication from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology Museum.

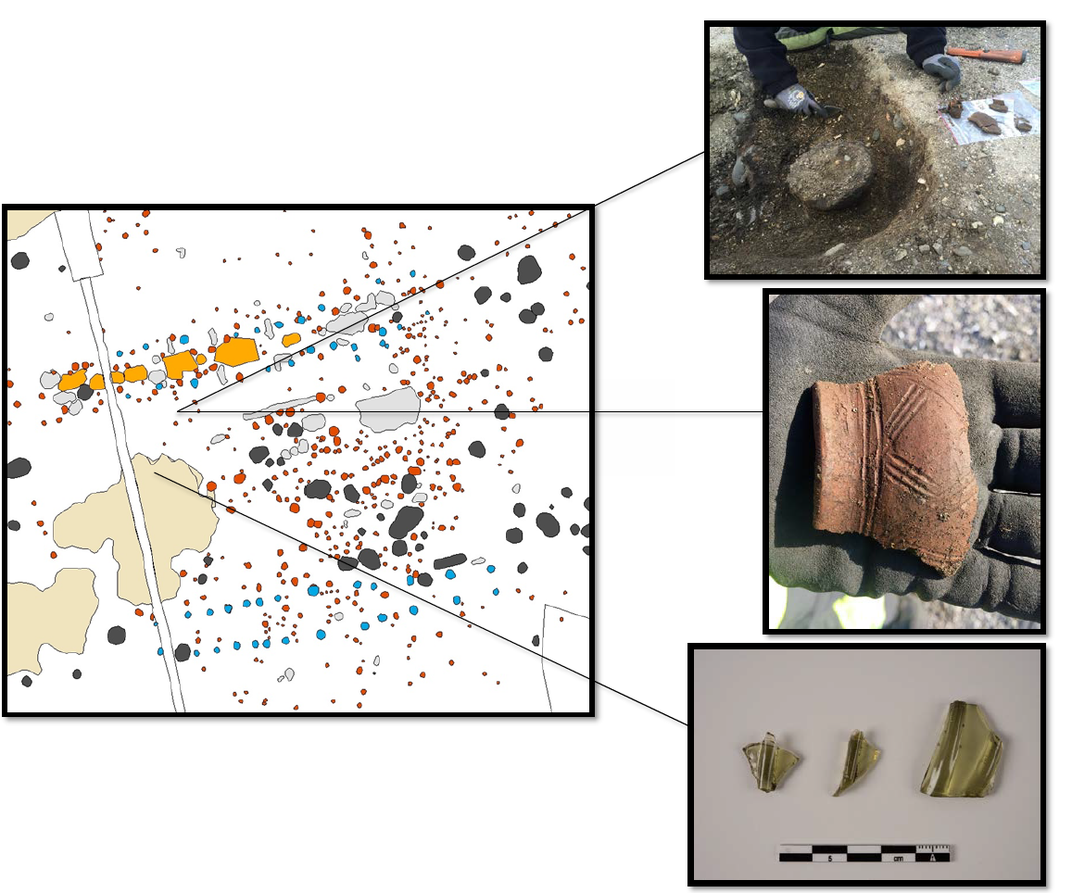

The new expansion will cover an area about three times the size of a shopping center, Bazilchuk reports. That means that the archeologists have a chance to look for the remains of longhouses, garbage pits called middens and other structures that can help build a picture of the ancient community.

The work will continue throughout 2016, but already the experts have found post holes for three large U-shaped longhouses, “where villagers would have gathered, honored their chieftain, and possibly stored food,” Newitz reports. But the best finds come from those refuse pits.

“Most of the time we don’t even find middens at all on sites that are older than the Mediaeval period,” project manager Ingrid Ystgaard tells Bazilchuk. The refuse includes clues to the villagers’ diet—old animal and fish bones preserved by the relatively acidic soil of the area. “Nothing like this has been examined anywhere in Norway before,” she adds.

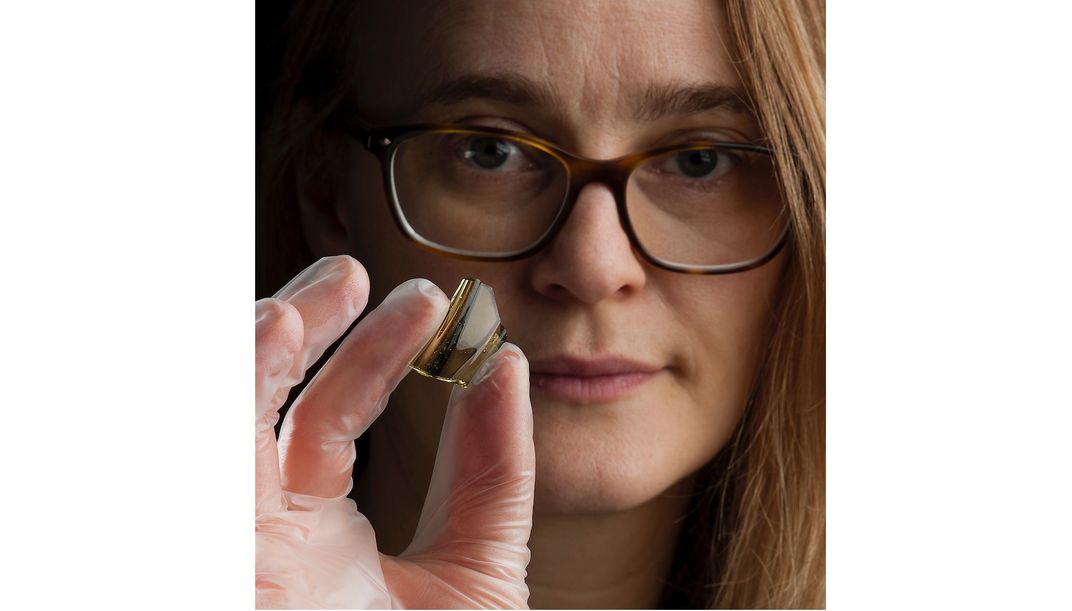

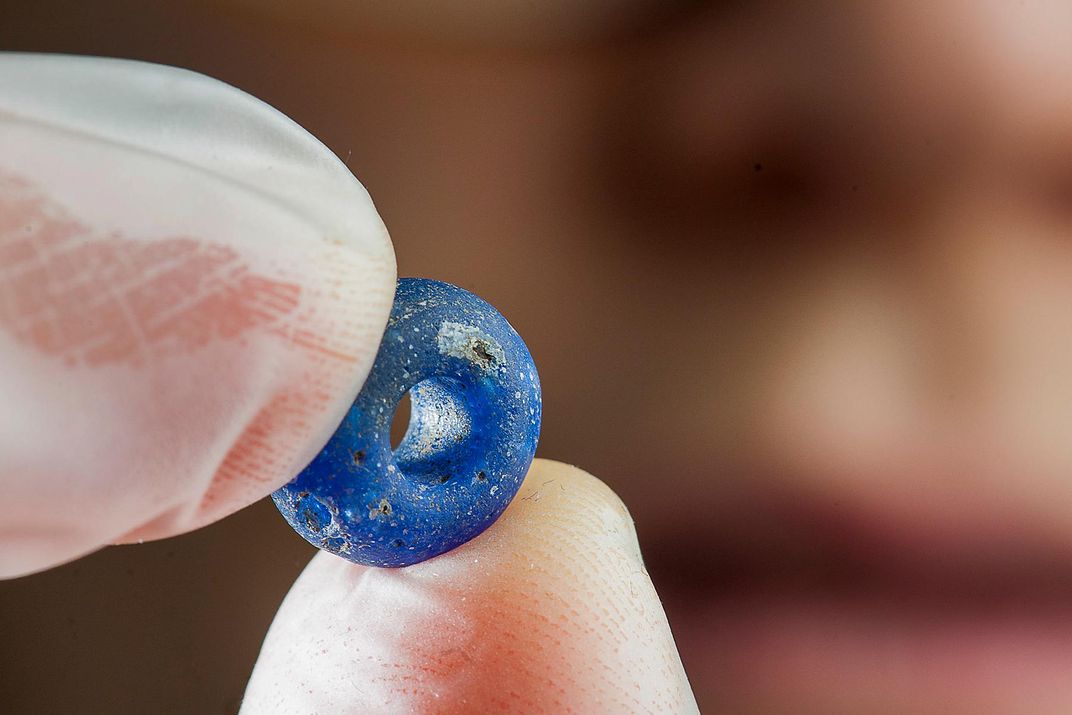

Other discarded items help paint a picture of life all those centuries ago. A blue glass bead, amber beads, a green drinking glass that may have been imported from the Rhine Valley in Germany and other finds are a testament to the wealth of the community. More intriguing findings will continue to come from the site as the archeologists carefully scrape away layers of dirt.

Hopefully the scientists will be able to tell more about the people who settled in such a strategic location. “[I]t was at the mouth of Trondheim Fjord, which was a vital link to Sweden and the inner regions of mid-Norway,” Ystgaard says.

For archaeologists, one ancient person’s trash really is treasure.