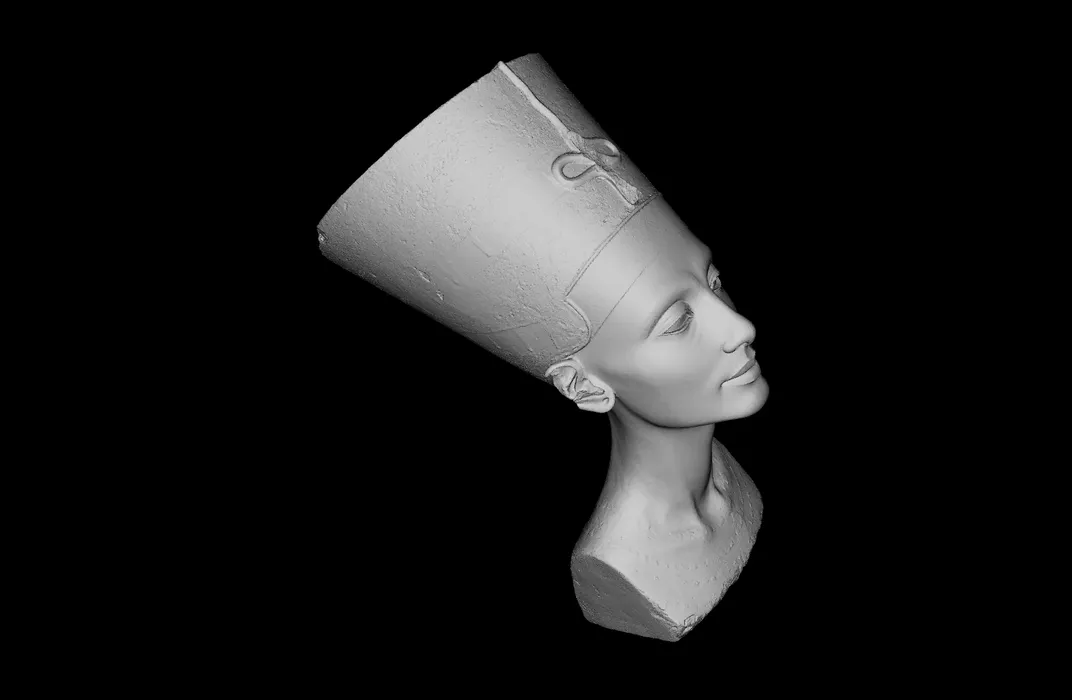

Thanks to Sneaky Scanners, Anyone Can 3D Print a Copy of Nefertiti’s Bust

Scans of the famous sculpture are free for the taking

Update March 9, 2016: Since this story was originally published, the veracity of the scan has been called into question. Analysis suggests that it is too refined for the equipment the artists used and some suggest the scan may have been copied from a scan commissioned by the Neues Museum. In an e-mail to Smithsonian.com, the artists say they can't verify the scan's origins because they gave the initial data to a third, unnamed party to process the data.

But the artists note that regardless of the veracity of the source, focusing on the data misses the point. "Art is about building new narratives, deconstructing power relations, not scanning techniques," writes Nora Al-Badri. "What we strived to achieve is a vivid discussion about the notion of possession and belonging of history in our museums and our minds."

Nefertiti’s bust might be one of the most famous archaeological finds of the 20th century, but it is also one of the most contentious. First discovered in an ancient Egyptian sculptor’s workshop in 1912, the sculpture of the ancient Egyptian queen has resided in the Neues Museum in Berlin on public view, but under heavy guard. Now, a pair of artists have released sneakily-taken 3D scans of Nefertiti’s bust, giving anyone with internet access and a 3D printer the chance to have their very own copy.

The bust is one of the Neues Museum’s most prized objects in its collection, making it the most closely watched. Visitors are not allowed to take photographs of Nefertiti’s likeness, and the museum has even kept 3D scans of the piece under strict control, Jamie Condliffe writes for Gizmodo. But last October, artists Nora Al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles entered the museum with 3D scanners hidden under their jackets and scarves. Using the secret scanners, Al-Badri and Nelles created a detailed 3D scan of the bust. After months of piecing together the information into a single, refined file, the two have released the scan on the internet under a Creative Commons license for anyone to use or remix as they like.

While a 3D-printed Nefertiti bust would spruce up any bookshelf, Al-Badri and Nelles didn’t take the scans just so people could use the bust as a decoration. For years, Germany and Egypt have argued over which country is the 3,500-year-old sculpture’s rightful home: Egyptian antiquities experts claim that the bust was illegally taken from the ruins it was discovered in, which German officials have hotly disputed, Claire Voon reports for Hyperallergic. Egyptians have demanded that the Neues Museum return the limestone-and-stucco statue to them, but the museum has so far refused.

“The head of Nefertiti represents all the other millions of stolen and looted artifacts all over the world currently happening, for example, in Syria, Iraq and in Egypt,” Al-Badri tells Voon. “Archaeological artifacts as a cultural memory originate for the most part from the Global South; however, a vast number of important objects can be found in Western museums and private collections. We should face the fact that the colonial structures continue to exist today and still produce their inherent symbolic struggles.”

The Neues Museum isn’t the only Western institution to hold disputed artifacts in its collection: the British Museum has held several marble statues originally taken from the Parthenon for nearly 200 years, and in 2010 the Metropolitan Museum of Art returned 19 different objects taken from King Tut’s tomb to Egypt. By secretly scanning Nefertiti’s bust and releasing them online, Al-Badri and Nelles hope to pressure the Neues Museum and others around the world into returning disputed artifacts to their countries of origin and opening their archives to the public, Kelsey D. Atherton reports for Popular Science.

“We appeal to [the Neues Museum] and those in charge behind it to rethink their attitude,” Al-Badri tells Voon. “It is very simple to achieve a great outreach by opening their archives to the public domain, where cultural heritage is really accessible for everybody and can’t be possessed.”

So far, the Neues Museum has not publicly responded to Al-Badri and Nelles’ actions, but others have. Recently, the American University in Cairo used the scans to 3D print their own copy of Nefertiti’s bust, and several Egyptian researchers have asked them for the data in order to further their own research. It’s unclear if Nefertiti’s bust will ever return to Egypt, so for now, 3D scans will have to do.