This “Lost Underwater City” Was Actually Made by Microbes

Though these formations may not be evidence of a lost city, they show off some intriguing chemistry

Several years ago, a group of snorkelers swimming near the Greek island of Zakynthos were amazed to discover what at first seemed like the ruins of an ancient city—strange stone cylinders and what appeared to be cobblestones set into the seafloor. The find set off speculation about the discovery of a long-lost city built by the ancient Greeks, but according to a new study published in the journal Marine and Petroleum Geology, these strangely-shaped rocks actually formed naturally over millions of years.

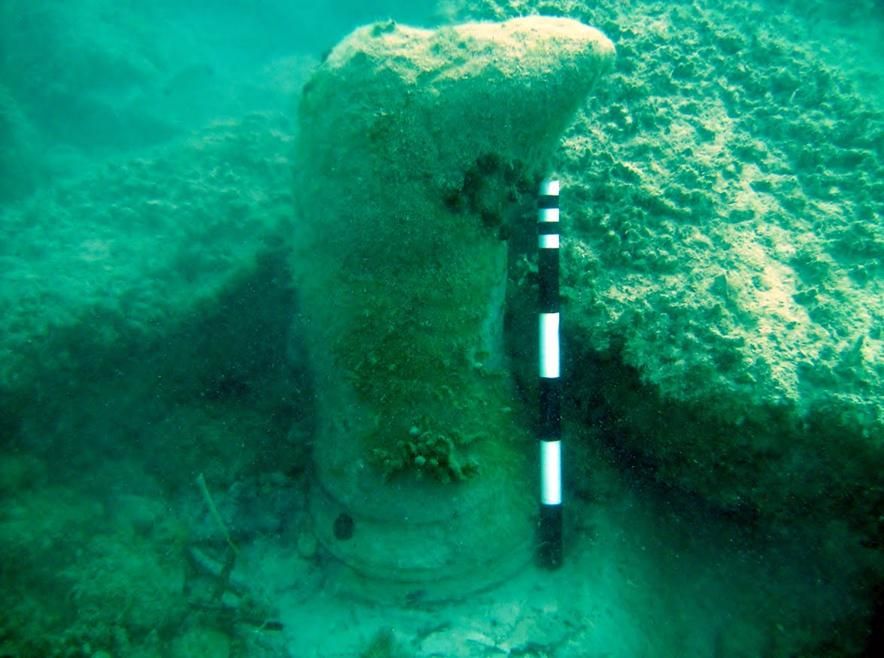

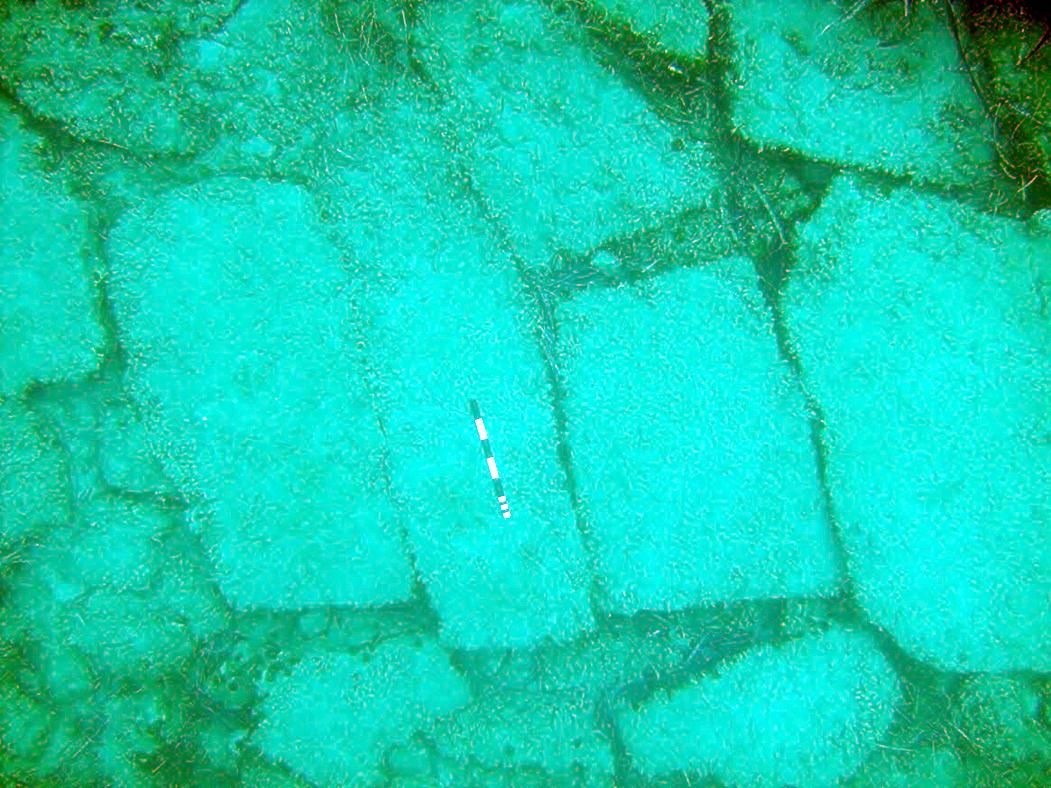

At first glance, these formations look man-made. Found 15 to 20 feet below the surface of the water, the site is littered with stone cylinders and cobblestone-like objects that resemble the foundations of an ancient, columned plaza. However, Julian Andrews, an environmental scientist at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom, says the site was lacking many the common signs of human activity.

“There’s no other evidence, nothing that suggests human civilization,” Andrews tells Smithsonian.com. “There’s no pottery, no coins, nothing else that usually goes along with these things.”

When Andrews and his colleagues analyzed the chemical makeup of the rocks, they found their hunch was right. What first appeared to be stone structures were actually naturally-occurring mineral formations that commonly form around natural sources of methane, which can be emitted as buried organic matter decays or methane leaks from veins of natural gas deep beneath the ocean floor. As some species of microbes feed on the methane, they produce a mineral called dolomite that often forms in seabed sediments.

Zakynthos sits nearby a well-known underwater oil field in the Mediterranean Gulf of Patras, which could explain where the methane feeding the dolomite-making microbes came from. According to Andrews, the formations’ odd shapes are likely the result of the various methane leaks sizes and how tightly microbes gathered around them to feed.

In larger leaks, the microbes could spread out and form mineral structures more evenly, resulting in the slab-like structures. Meanwhile, smaller sites that leaked methane in a tight jet may have led the microbes to make column-like and doughnut-shaped formations as they clustered close around the smaller food source.

“Essentially what you’ve got are bacteria that are fossilizing the plumbing system,” Andrews says.

The structures appear to date back to the Pliocene Epoch about 2.6 million years ago. They're not unique—similar sites have been found around the world, in places like California’s Monterey Bay, the Gulf of Cadiz in the Mediterranean, and the oil-rich North Sea.

“These kinds of things in the past have been found normally reported in very deep water, thousands of meters [down],” Andrews says. “In that respect, they’re quite common around the world. But what’s unusual about these is that they’re in very shallow water.” Their presence in this shallow water suggests that there is a partially-ruptured fault just below the region’s sea floor.

While marine archaeology buffs might be disappointed to learn that the formations aren’t the remains of a long-forgotten Greek city, they still play an important role in the local ecosystem. Andrews says the stone-like structures can act like coral reefs by providing habitats and shelter for fish and other undersea creatures.

The stone shapes may just be a fluke of nature, but they provide an interesting insight into the natural processes going on beneath the ocean’s floor.