Iconic Portrait of French Chemist and His Wife Once Looked Entirely Different

Jacques-Louis David’s 1789 painting originally depicted Antoine and Marie Anne Lavoisier as wealthy elites, not modern scientists

:focal(411x289:412x290)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eb/8d/eb8d6a10-1db4-49f6-a12c-570c79729959/fdasfsdfdsaf.jpg)

Conservator Dorothy Mahon first noticed something odd about French painter Jacques-Louis David’s 1788 portrait of the Lavoisiers—a married couple known for their contributions to modern chemistry—in March 2019. As Mahon carefully removed faded varnish from the nine-foot-tall artwork, she noticed strange spots of red peeking out from beneath the paint around Marie Anne Lavoisier’s head, hints of more red paint under the noblewoman’s blue dress and inexplicable cracks around the table where Antoine Lavoisier sat.

These faint clues eventually led a team of art sleuths to a shocking discovery: that David’s portrait once looked completely different, as Nancy Kenney reports for the Art Newspaper. Mahon and her colleagues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art published their findings in the Burlington magazine and Heritage Science journal this week.

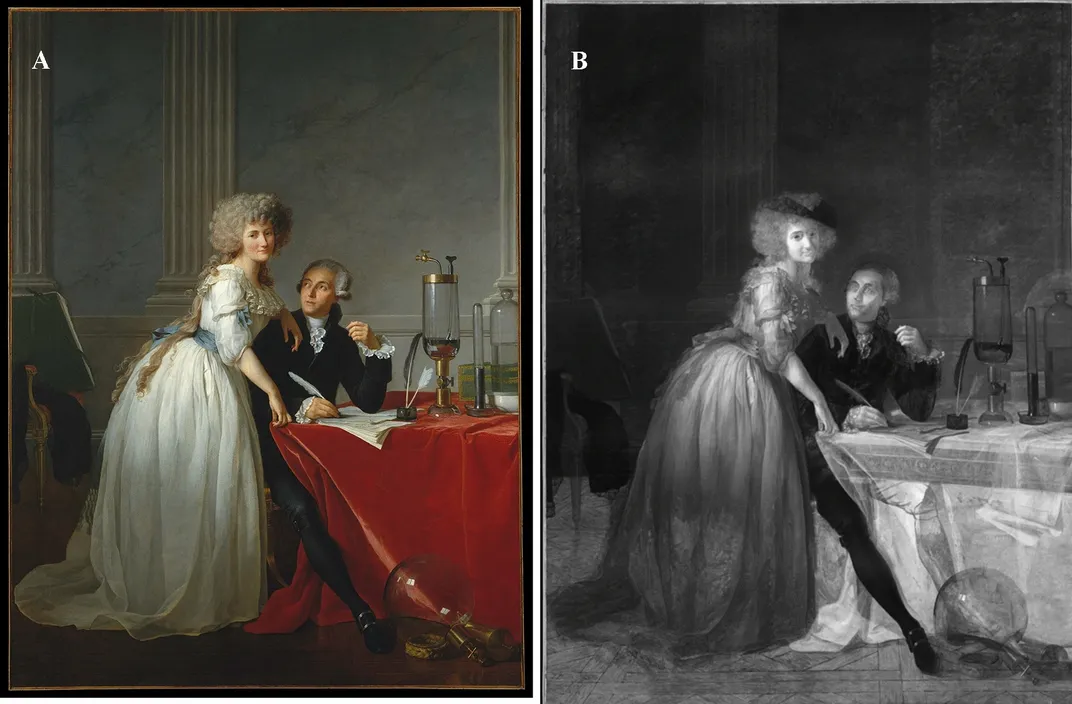

Today, David’s stunning double portrait is renowned for its depiction of the French couple as modern scientific innovators, writes the research team in a Met blog post. The pair don modest but fashionable clothing and are surrounded by elegant scientific equipment.

The portrait reflects historical reality—to an extent. As Artnet News notes, Antoine was highly regarded in late 18th-century France for helping to develop the metric system and discovering the role that oxygen plays in combustion. Though she went unrecognized at the time, Marie also played an instrumental role in these achievements. Antoine is often called the “father of modern chemistry,” and scholars have, in recent decades, described Marie as the subject’s “mother.” A skilled artist, Marie also contributed the engravings for her husband’s books.

When the couple first commissioned David to paint their portrait, they had a specific vision in mind. In the original painting, the spouses wear luxurious clothing; Antoine reclines near a bare tabletop inlaid with gilt brass details. Instead of his current spare black suit, he wears a long brown coat with seven bronze buttons. The scientific instruments are nowhere to be seen.

Most surprisingly, Marie once wore an enormous plumed hat topped with artificial flowers. All told, the Lavoisiers seemed intent on depicting themselves not as scientists, but as an elite tax collector and his wife luxuriating in their wealth.

“The revelations about Jacques-Louis David’s painting completely transform our understanding of the centuries-old masterpiece,” says the Met’s director, Max Hollein, in a statement.

Using non-invasive infrared reflectography and macro X-ray fluorescence mapping, the researchers spent around 270 hours scanning the canvas in its entirety, per the blog post. The museum first purchased the David portrait in 1977, when some of the technologies now used to study the work did not yet exist.

“More than 40 years after the work first entered the [m]useum’s collection, it is thrilling to gain new insights into the artist’s creative process and the painting’s evolution,” adds Hollein.

So, why did David make the changes? The choice might have been inspired by the French Revolution and its overthrow of the ancien régime, which began just a year after the portrait’s completion, in 1789.

David reportedly planned to debut the original portrait at a salon in 1789, but he withdrew the work on the advice of royal authorities. Regardless, Antoine’s status as a wealthy tax collector marked him as an enemy of the revolutionary cause: He was executed by guillotine in 1794, during the Reign of Terror, per Encyclopedia Britannica. His wife was spared.

“I think the very tempting theory is to line it up with the politics and say, ‘Oh, they wanted to move themselves away from looking like the tax collector class,’” curator David Pullins tells the Art Newspaper. “… [But] I think it’s difficult to push it that far.”

At the very least, says the curator in the statement, “now we see that another identity was, quite literally, concealed in the present portrait. It is an alternate lens through which to see the Lavoisiers—not for their contributions to science but as members of the wealthy tax collector class, a status that funded their research but ultimately led Lavoisier to the guillotine in 1794.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4c/e0/4ce07992-a78e-4b66-b802-99d6b55f58ec/version_jpg.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)