These Iron Age Swedish Warriors Were Laid to Rest on Luxurious Feather Bedding

Researchers say the various types of bird feathers used may hold symbolic significance

:focal(555x345:556x346)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/e7/69e70b5b-5ca3-4ef2-8fc7-29426a9f9801/1-warriorsdown.jpeg)

More than a millennium ago, two Iron Age warriors in Sweden’s Valsgärde burial ground were sent to the afterlife in boats equipped with helmets, swords and shields. To ensure the pair’s comfort, new research published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports suggests, the men were also buried with luxurious feather bedding.

As Amy Woodyatt reports for CNN, the seventh-century down bedding is the oldest ever discovered in Scandinavia. Its presence could indicate that the warriors were high-status figures in their society.

Though wealthy Greeks and Romans used down bedding centuries earlier, the practice was rare among European elites prior to the medieval period, says lead author Birgitta Berglund, an archaeologist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology’s NTNU University Museum, in a statement.

According to Ars Technica’s Kiona N. Smith, one of the men’s bedding was stuffed mostly with duck and goose down, while the other’s contained cushions with feathers from a large range of birds: geese, ducks, sparrows, crows, grouse, chickens, and eagle-owls—a type of large horned owl. Berglund says the mix of feathers may have been chosen for its symbolic meaning, as seen in Nordic folklore.

“For example, people believed that using feathers from domestic chickens, owls and other birds of prey, pigeons, crows and squirrels would prolong the death struggle,” she explains in the statement. “In some Scandinavian areas, goose feathers were considered best to enable the soul to be released from the body.”

One of the boat burials included a headless eagle-owl that was probably a hunting companion. The removal of the raptor’s head may have been a way to ensure that it could not return from the dead and perhaps be used as a weapon by the dead warrior. As the researchers note in the study, the Vikings who inhabited the region after the warriors’ demise sometimes laid their dead to rest with bent swords—probably to stop the deceased from using the weapons.

“We believe the beheading had a ritual significance in connection with the burial,” says Berglund in the statement. “It’s conceivable that the owl’s head was cut off to prevent it from coming back. Maybe the owl feather in the bedding also had a similar function?”

The archaeologist adds that boat graves from the same period found in Estonia also contained two birds of prey with severed heads.

The Valsgärde burial ground was used for more than 1,000 years, up until the 11th or 12th century A.D. It’s best known for the boat graves, which date to the 600s and 700s A.D. The two boats examined in the new research were each around 30 feet long, with room for two to five pairs of oars. They contained cooking tools and weapons, and animals including horses were buried nearby.

“The buried warriors appear to have been equipped to row to the underworld, but also to be able to get ashore with the help of the horses,” says Berglund in the statement.

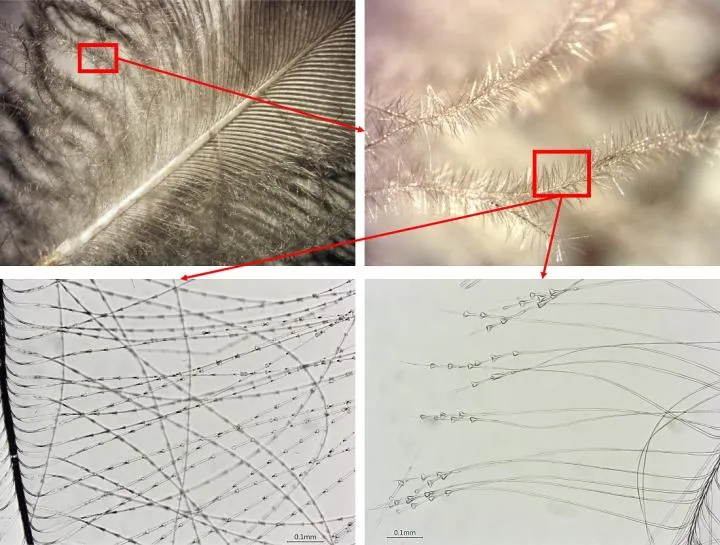

Study co-author Jørgen Rosvold, a biologist at the Norwegian Institute for Natural History (NINA), had to process the centuries-old feathers to identify which species they came from.

“It was a time consuming and challenging job for several reasons,” he says in the statement. “The material is decomposed, tangled and dirty. This means that a lot of the special features that you can easily observe in fresh material has become indistinct, and you have to spend a lot more time looking for the distinctive features.”

Nonetheless, Rosvold adds, he was eventually able to tell the feathers of different species apart.

“I'm still surprised at how well the feathers were preserved, despite the fact that they’d been lying in the ground for over 1,000 years,” he says.

When the researchers began studying the feather bedding, they suspected that the down might have been imported as a commodity from the coastal community of Helgeland, north of the gravesite. Though this didn’t turn out to be the case, the analysis did end up providing insights on how humans were connected to different kinds of birds in ancient Sweden.

“The feathers provide a source for gaining new perspectives on the relationship between humans and birds in the past,” says Berglund in the statement. “Archaeological excavations rarely find traces of birds other than those that were used for food.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)