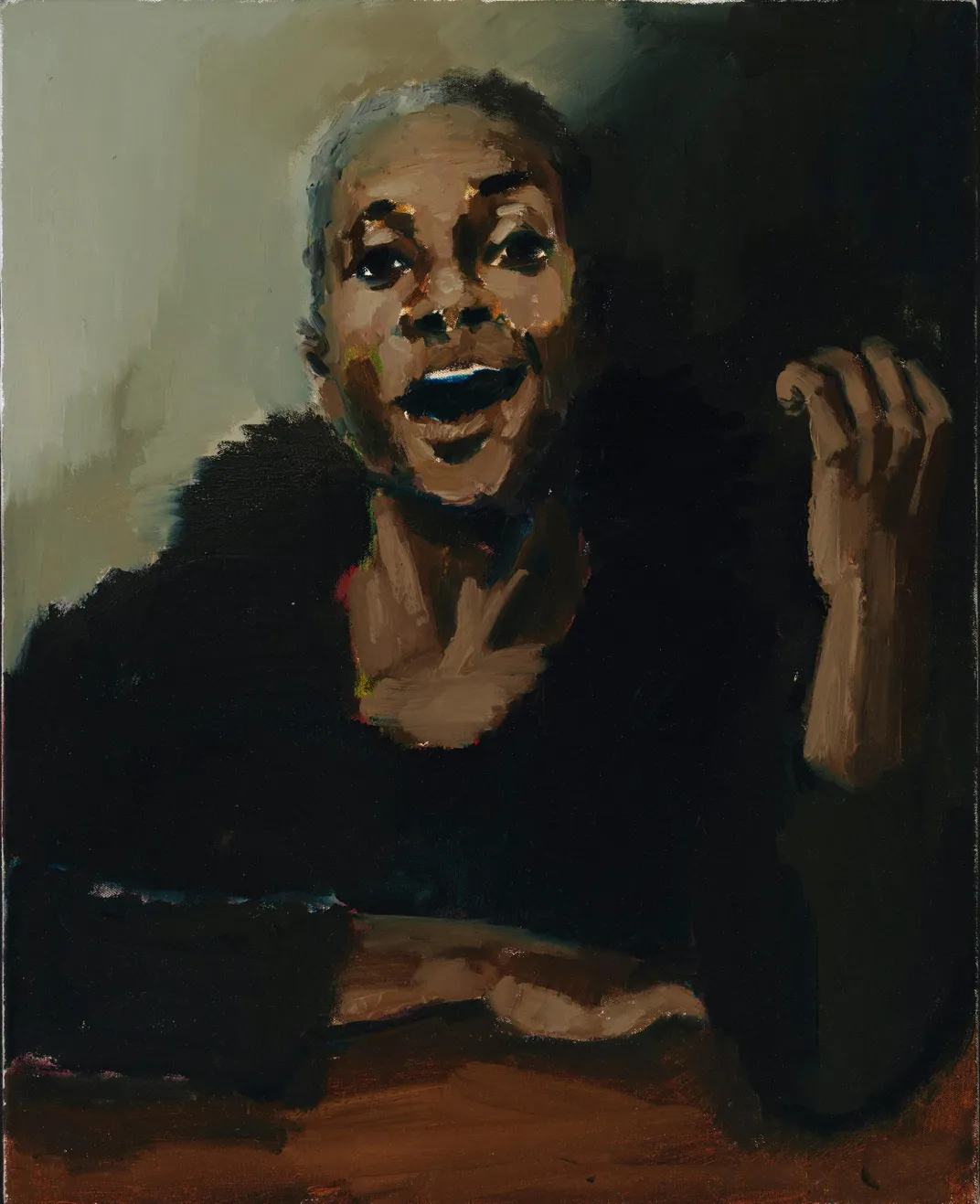

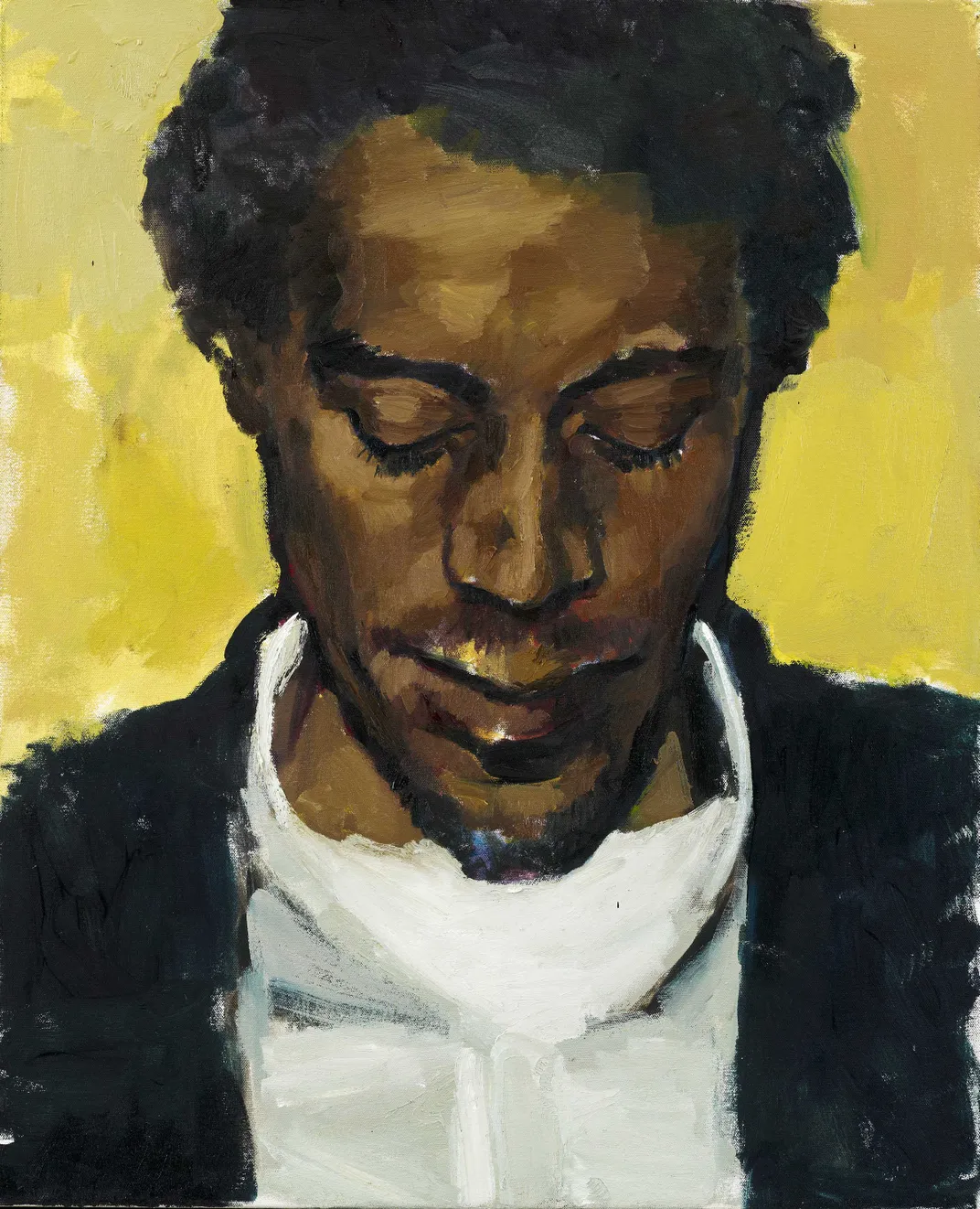

Stunning Paintings of Fictitious Black Figures Subvert Traditional Portraiture

Riffing on the genre’s long history, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s innovative works raise questions about black identity and representation

:focal(807x548:808x549)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cd/73/cd739386-c728-42c8-aa91-3a315f55b99a/lynette.jpg)

For much of European history, portraits offered powerful individuals the chance to convey their wealth and strength through the canvas. In some works, details ranging from the aggressive stance and elaborate garb of a king to the elegant repose of a wealthy socialite spelled out influence; in other studies, including Leonardo da Vinci’s famous Mona Lisa, artists sought to reproduce their sitters’ emotional or psychological states.

British artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s contemporary oil portraits take a similar yet strikingly new approach to the artistic genre. Drawing inspiration from Old Master paintings and private family photographs, she works quickly in the studio, sometimes crafting a composition in a single day. Most significantly, her elegant subjects aren’t wealthy patrons, but rather figments of the imagination.

Yiadom-Boakye’s innovative approach to portraiture makes her one of the “most important figurative painters working today,” according to a statement from Tate Britain. On view now through May 2021, the London gallery’s latest show, “Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly in League With the Night,” unites 80 of the artist’s paintings from 2003 to the present, giving viewers an unprecedented chance to explore the range and depth of her evolving practice.

Born in London to Ghanaian parents in 1977, Yiadom-Boakye earned a Master’s degree from the Royal Academy of Arts and was a 2013 nominee for the prestigious Turner Prize. She draws inspiration from private scrapbooks, as well as the portraiture of Goya, Manet and John Singer Sargent. Walter Sickert, a 20th-century British painter known for favoring muted, dark atmospheric tones, has also influenced her work, reports Rachel Spence for the Financial Times.

Yiadom-Boakye’s large-scale oil paintings riff on historical portraiture conventions while defying easy categorization. Wrist Action (2010), for instance, depicts a smiling black man framed against a shadowy background. Perched on a seat, the figure extends a strange, bright-pink gloved hand toward the viewer.

As the Financial Times notes, Yiadom-Boakye creates her subjects, rendered in often-abstract brushstrokes, just “as writers build fictional protagonists.” Her lush compositions feature exclusively black protagonists.

“Dark jumper, brown background, black hair and black skin,” writes Jonathan Jones in a review for the Guardian. “Yiadom-Boakye paints black people, and in the most hallowed of traditional European art forms: oil painting on canvas.”

These fictionalized figures include young girls playing on a hazy beach in Condor and the Mole (2011), a man gazing at the viewer and reclining on a checked red-and-blue blanket in Tie The Temptress to The Trojan (2016), and a group of young men leaning and stretching against a ballet barre in A Passion Like No Other (2012).

“It’s like you’ve taken a wrong turn and ended up in the 18th-century galleries,” Jones adds. “Except the black people who only play servile, secondary roles in those portraits now occupy the foreground and the high spiritual plane once reserved for white faces in art.”

Yiadom-Boakye is an avid writer and reader, and she often gives her works literary titles that suggest mysterious storylines without offering overt explanations.

“I write about the things I can’t paint and paint the things I can’t write about,” she said in a 2017 interview with Time Out’s Paul Laster. Per the Financial Times, this Tate survey—the largest exhibition of her work to date—features a list of the artist’s favorite books, including works by James Baldwin, Shakespeare, Zora Neale Hurston and Ted Hughes, in its catalog.

“Her titles run parallel to the images, and—like the human figures they have chosen not to describe or explain—radiate an uncanny self-containment and serenity,” wrote critic Zadie Smith in a New Yorker review of a 2017 Yiadom-Boakye show. “The canvas is the text.”

Viewers across the world can explore the exhibition through interactive materials on Tate Britain’s website. Art lovers can also virtually attend a free online performance, “Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Stillness,” accessible on YouTube and through this website at 3 p.m. Eastern time on December 11. The performance will feature textile and performance artist Enam Gbewonyo and composer Liz Gre fusing “sound and movement in an ode to Blackness and repose,” per the event description.

“Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings often feature Black figures in moments of rest and stillness,” the statement says. “Inspired by her work, and as a difficult and tiring year comes to a close, this collaborative performance encourages online audiences to experience a shared space of healing in Tate Britain’s galleries.”

“Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly in League With the Night” is on view at Tate Britain in London through May 9, 2021.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/75/9d/759d1232-c742-408c-bb15-27ebb6cd1497/lynette_yiadom-boakye_courtesy_of_the_artist_marcus_leith.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/a1/49a11066-84ee-4514-a154-0cb370e42cb0/lynette_yiadom-boakye_install_4_.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)