Historic Photos of Baltimore Show the Real-Life “Hairspray”

Hairspray Live! fans, learn the history behind the beloved story

When John Waters’ original film version of Hairspray debuted in 1988, it was already looking back at a decades-old world. But while the movie and the musical both touch on issues of racial segregation that plagued Baltimore in the 1960s, the reality was that the city—and the country as a whole, for that matter—was much more starkly divided than it might seem through this nostalgic lens.

Hairspray’s plot revolves around the efforts of the teenage Tracy Turnblad first to win a spot on a popular dance show, and later to desegregate it with the help of her friends and family. Though Tracy’s efforts to get “The Corny Collins Show” to allow black dancers on outside of its monthly “Negro Night” are ultimately successful and bring her community together, this would have been almost unthinkable in the real world of 1962. Still, if it was going to happen anywhere in the United States, Baltimore wasn't a bad place to start.

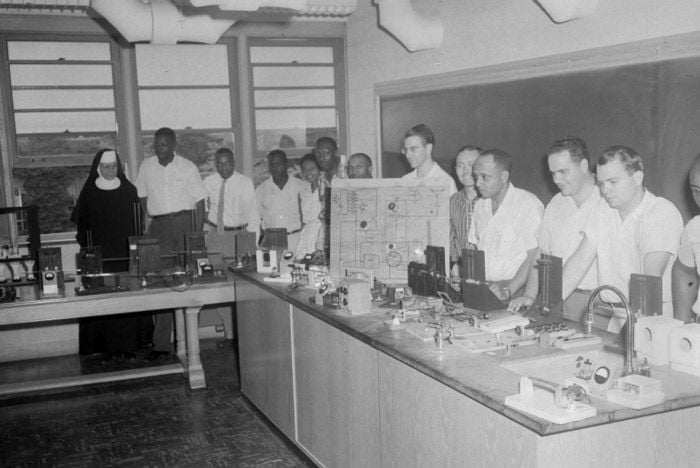

While the city faced plenty of protests and issues around segregation throughout the Civil Rights Movement, the city was right on the frontlines of social change. In 1952, Baltimore's Polytechnic Institute was forced to become an integrated school, and the city became the first in the South to officially integrate its public schools after the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education two years later, Taunya Banks writes in Hairspray in Context: Race, Rock 'n Roll and Baltimore. Throughout the 1950s, the city began to relax its attitude towards racial segregations, as more and more businesses and public institutions began to open their doors to black people.

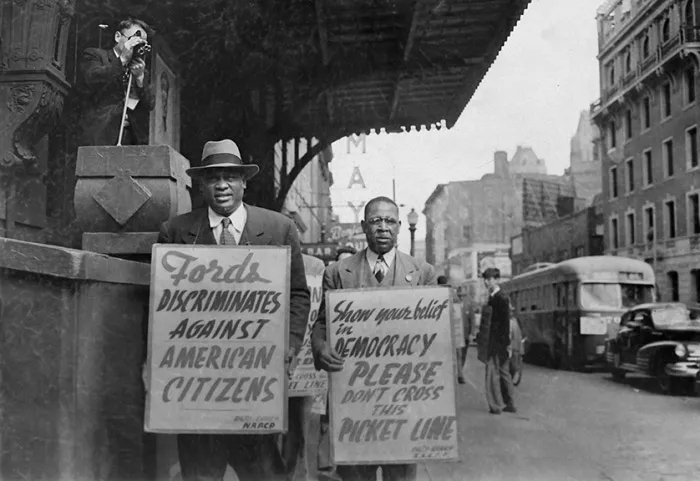

Still, Baltimore was far from being free of racial tensions. Take, for instance, “The Buddy Deane Show,” which aired on WJZ-TV in Baltimore from 1957 until 1964. While this real-life dance show inspired Hairspray’s “Corny Collins Show,” becoming an successful model of racial integration was not part of its legacy.

"When my show went on, management discussed the matter and decided they would follow 'the local custom' of segregation, and we were going to have separate but equal," Deane told Tony Warner for the book Buddy's Top 20: The Story of Baltimore's Hottest TV Dance Show and the Guy Who Brought It to Life, as Laura Wexler reported in The Washington Post in 2003.

While “The Buddy Deane Show” did feature monthly nights allowing black church groups and Boys and Girls Clubs, this show and others like it across the country were controversial simply for introducing American teenagers to black musicians and dances. As Banks writes, the very act of a television show featuring white teenagers listening to black singers and doing dance moves drawn from black dance halls was enough to inspire segregationists to hand out fliers warning white parents about letting their kids listen to “race music.”

While the musical may end with Tracy cheerfully declaring the “Corny Collins Show” integrated, the “Buddy Deane Show” didn’t have such a cheerful fate. Though black and white dancers did stage a surprise, forceful integration of the program on August 12, 1963, by storming the stage, it sparked so many threats that the show was canceled a few months later—despite the fact that Deane and the producers did want to integrate the show, reports Wexler.

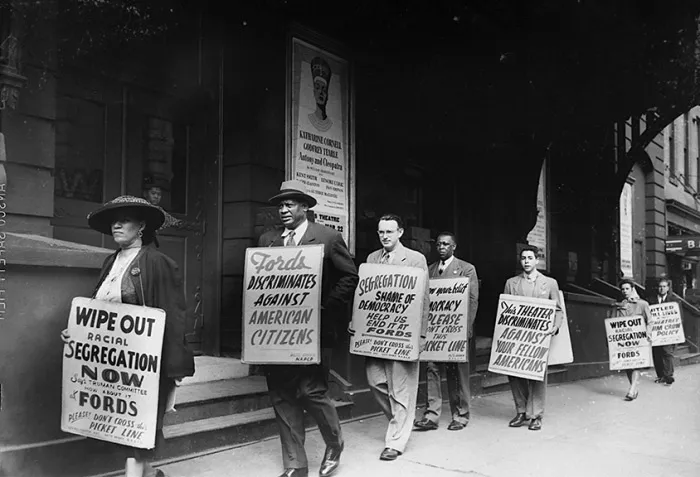

However, Baltimore was a staging ground for some serious clashes over segregation at the time. In 1962, the same year that Hairspray takes place, the Maryland Court of Appeals ruled that a group of high school and college students were rightfully arrested and convicted for staging a sit-in at the segregated Hooper’s Restaurant in downtown Baltimore. That same year, Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke to an audience of thousands at Baltimore’s Willard W. Allen Masonic Temple urging them to continue demonstrating against segregation. And of course, the following two years alone saw King lead the iconic March on Washington and Congress passing the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibiting segregation public places and the workplace, Banks writes.

Though Hairspray successfully employs kitsch to address the very real issues facing Baltimore and the rest of the country at the time, it does show these issues through a Hollywood sheen—“The Corny Collins Show” is integrated, and everyone presumably lives happily ever after by the story's close. But, as history shows, enacting real change takes sustained resistance (though having a compelling soundtrack doesn't hurt).