This Eighteenth-Century Robot Actually Used Breathing to Play the Flute

It was one of a trio of automata that had functions like living creatures

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/10/79/1079d0a3-1260-4b24-9b6c-61953f9d771c/flute_with_musicial_notes.jpg)

Inventor and artist Jacques de Vaucanson was born on this day in 1709. He was good at his job—as in the case of The Flute Player, maybe too good.

The Flute Player was a sort of pre-robot called an automaton. It was a human-shaped machine that literally played the flute using the same method as a human would: air. It was this that made it the perfect Enlightenment-era machine, writes Gaby Wood in an excerpt from her book on androids featured in The Guardian. It was an actual mechanical recreation of a man, as perfect as the tools of the time would allow. When Vaucanson first designed the creature, he found its metal hands couldn’t grip or finger the flute, so he did the only sensible thing and gave the hands skin.

And it was both a bit of a coup and entirely unsettling, she writes:

Nine bellows were attached to three separate pipes that led into the chest of the figure. Each set of three bellows was attached to a different weight to give out varying degrees of air, and then all pipes joined into a single one, equivalent to a trachea, continuing up through the throat and widening to form the cavity of the mouth. The lips, which bore upon the hole of the flute, could open and close and move backwards or forwards. Inside the mouth was a moveable metal tongue, which governed the air-flow and created pauses.

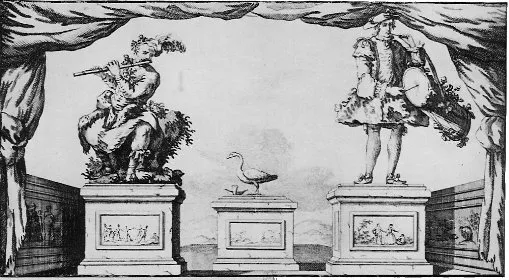

“The automaton breathed,” she concludes. After showing his creation, he created two more automata, one of which was a humanoid tambourine player. Vaucanson, a driven inventor, eventually sold the trio and went on to other projects, writes Wood.

The one he’s best remembered for, though, wasn’t human at all: it was a duck that flapped its wings, moved its feet, ate and even excreted what looked like digested food. To pull this trick off, Vaucanson is credited with the invention of the first rubber tubing. Again, “Vaucanson claimed to have replicated the actions of a living animal, showing his mechanism (rather than covering it with feathers) so that the audience could see it was not trickery, but the wonders of mechanics,” writes historian William Kimler.

Vaucanson’s creations eventually disappeared from history, Wood writes. But they were the product of a particular historical moment. When the inventor—who by all accounts had a great deal of innate talent for machinery—made his automata, the great thinkers of the day believed that humans were little but a really good kind of machine. Philosopher Rene Descartes published his Treatise on Man in 1664, writes historian Barbara Becker, and after its printing “the notion that humans were not only machine builders, but the ultimate it self-moving machines, inspired a new way of thinking about man-made automata.” One story about Descartes says he even built his own automaton.

In this climate, Vaucanson—who initially thought up the flute player in a fever dream, according to Wood—was able to gain the financing, public interest and the technology to build mechanical men.