The CIA Is Celebrating Its Cartography Division’s 75th Anniversary by Sharing Declassified Maps

Decades of once-secret maps are now freely available online

As much as James Bond is defined by his outlandish gadgets, one of the most important tools for real-life spies is actually much less flashy: maps. Whether used to gather information or plan an attack, good maps are an integral part of the tradecraft of espionage. Now, to celebrate 75 years of serious cartography, the Central Intelligence Agency has declassified and put decades of once-secret maps online.

These days, the C.I.A. and other intelligence agencies rely more on digital mapping technologies and satellite images to make its maps, but for decades it relied on geographers and cartographers for planning and executing operations around the world. Because these maps could literally mean the difference between life and death for spies and soldiers alike, making them as accurate as possible was paramount, Greg Miller reports for National Geographic.

“During [the 1940s], in support of the military’s efforts in World War II...cartographers pioneered many map production and thematic design techniques, including the construction of 3D map models,” the C.I.A. writes in a statement.

At the time, cartographers and mapmakers had to rely on existing maps, carefully replicating information about enemy terrain in pen on large translucent sheets of acetate. The final maps were made by stacking these sheets on top of one another according to what information was needed, then photographed and reproduced at a smaller size, Miller reports. All of this was done under the watchful eye of the then-26-year-old Arthur H. Robinson, the Cartography Center’s founder.

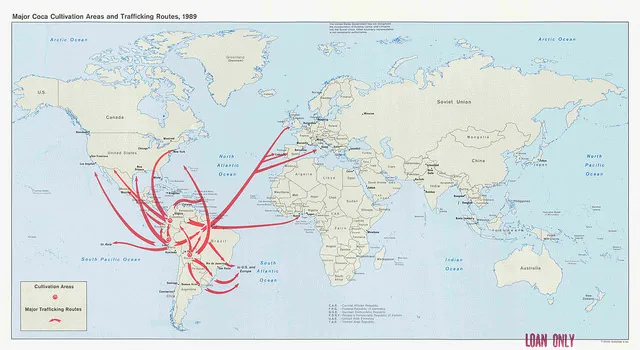

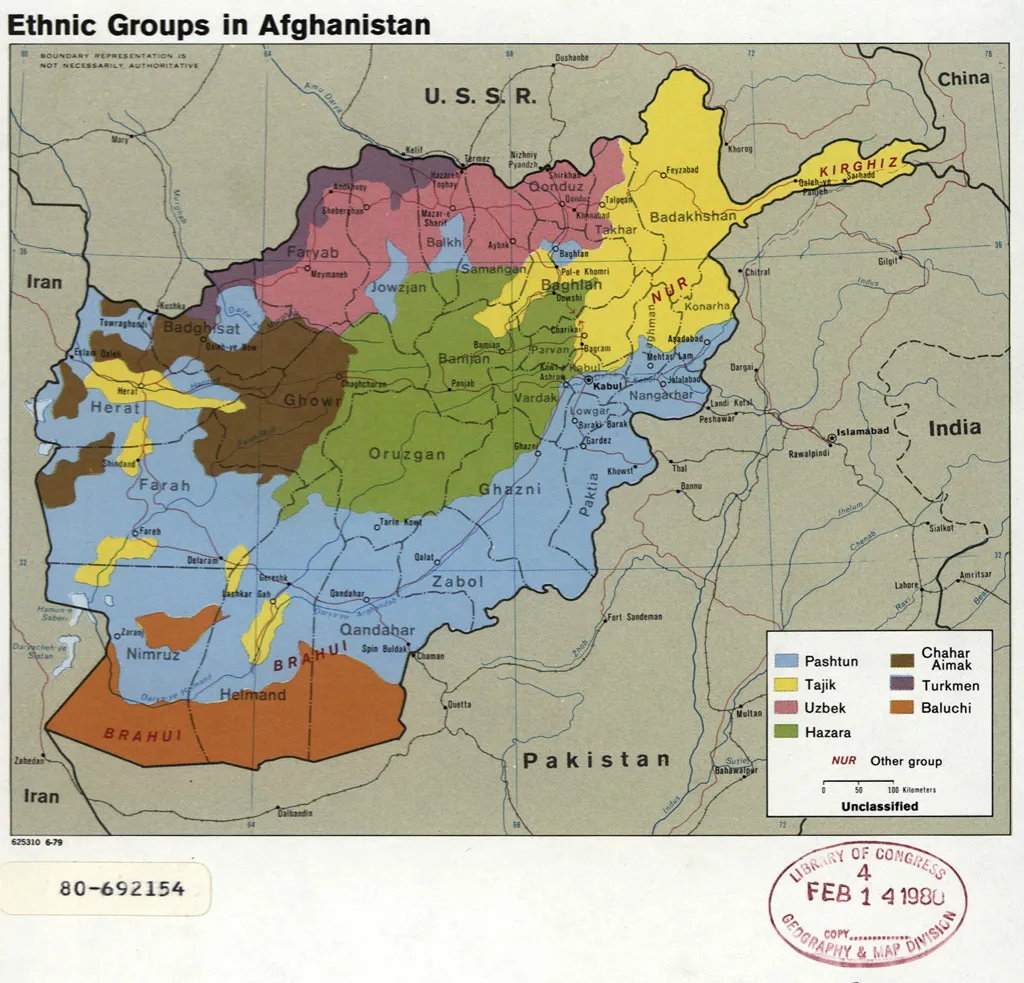

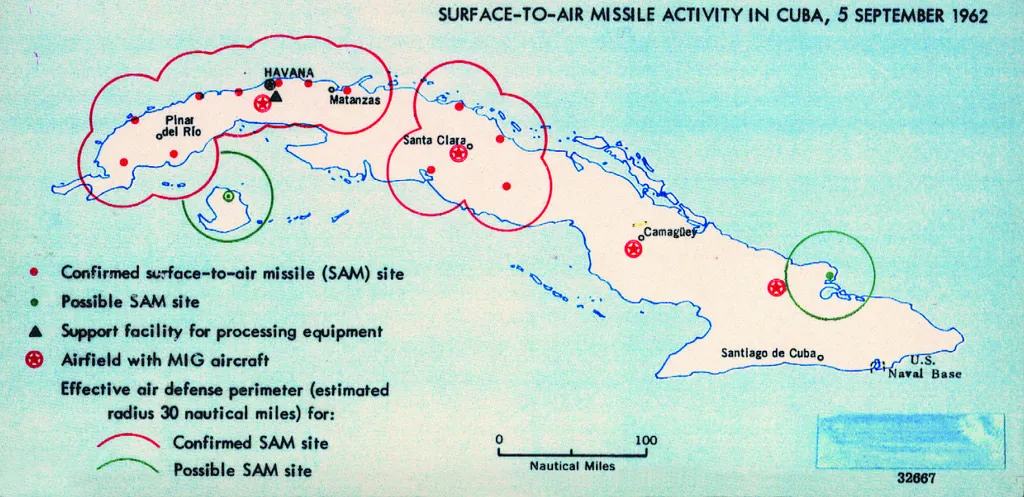

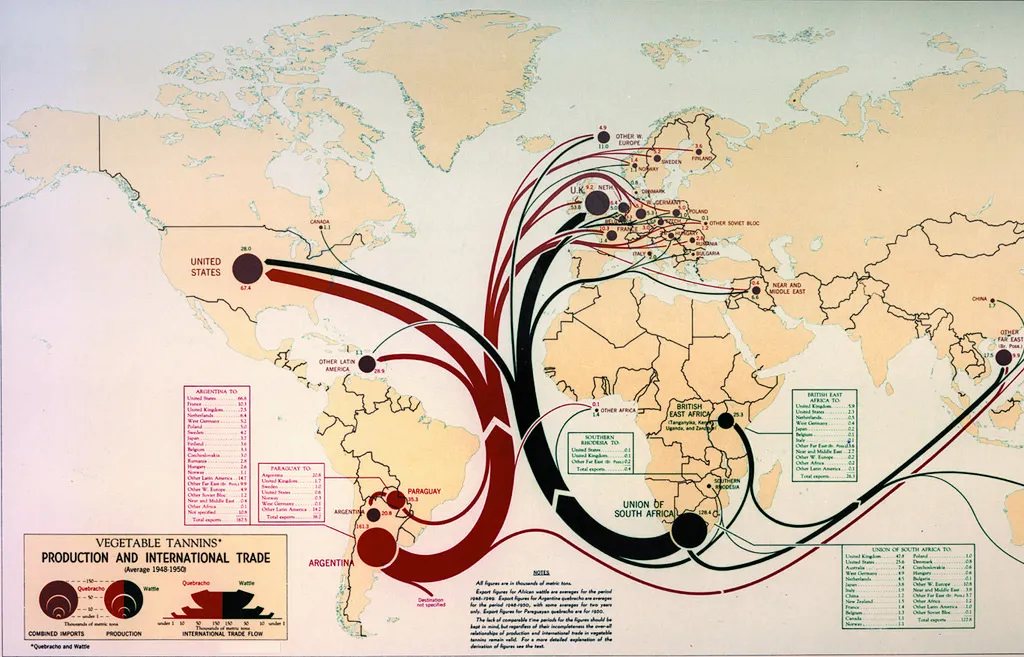

Though World War II-era intelligence services like the Office of the Coordinator of Information and the Office of Strategic Services eventually morphed into the C.I.A. as we know it today, the Cartography Center was a constant element of the United States’ influence abroad. Looking through the collection of declassified maps is like looking into a series of windows through which government officials and intelligence agents viewed the world for decades, Allison Meier reports for Hyperallergic. From the early focus on Nazi Germany and the Japanese Empire, the maps show shifting attention towards the Soviet Union, Vietnam and the Middle East, to name just a few examples.

As interesting as these maps are to look at, it’s sobering to remember that they played a major role in shaping global politics of the 20th century. These were the documents that U.S. government officials relied on for decades, whether it was predicting global trade in the 1950s or preparing for the Invasion of the Bay of Pigs in Cuba in the 1960s. Intelligence briefings may more often be done digitally these days, but whatever medium a map is made in, knowing where you are going remains critical to understanding—and influencing—world affairs.