You Can Now Explore 103 ‘Lost’ Hokusai Drawings Online

Newly acquired by the British Museum, the trove of illustrations dates to 1829

:focal(2159x1695:2160x1696)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9e/b5/9eb55431-cc90-4853-9f09-0229f9342318/060.jpg)

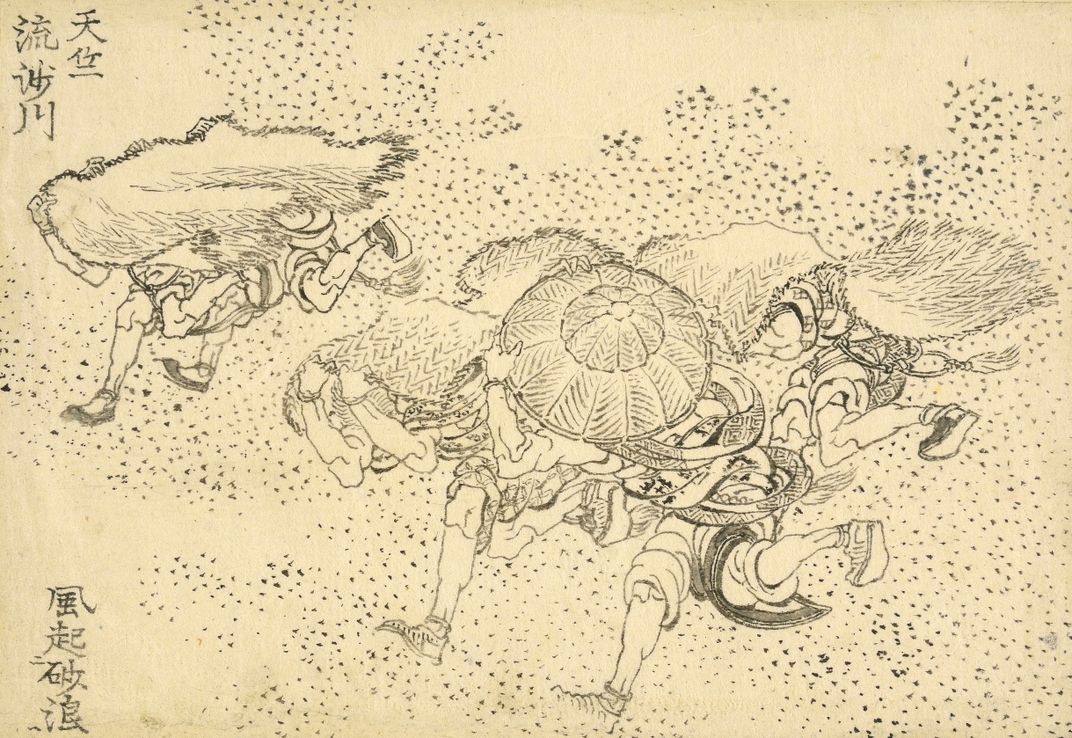

Earlier this month, the British Museum announced its acquisition of a trove of newly rediscovered drawings by Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai, who is best known for 19th-century masterpiece The Great Wave Off Kanagawa. Visitors can’t yet see the illustrations in person, but as the London institution notes in a statement, all 103 works are now available to explore online.

In 1829—around the same time Hokusai created The Great Wave—the artist crafted a series of small drawings intended for publication in a book titled Great Picture Book of Everything, reports Gareth Harris for the Art Newspaper.

But the book was never published, and after Hokusai died in 1849, the drawings came into the possession of Art Nouveau jeweler Henri Vever. Five years after Vever’s death in 1943, a collector bought the artworks, opting to keep them out of public view for the next seven decades. The sketches only resurfaced last June, when the British Museum purchased them with support from the Art Fund charity.

Per Atlas Obscura’s Claire Voon, producing the picture book as planned would have destroyed the drawings. To create such texts, professional wood cutters and printers pasted illustrations onto woodblocks and used them as stencils for carving a final image. Historians don’t know why the book was never published, but its failure to come to fruition actually ensured the illustrations’ survival.

The newly digitized drawings depict religious, mythological, historical and literary figures, as well as animals, flowers, landscapes and other natural phenomena, according to the statement. Subjects span ancient Southeast and Central Asia, with a particular emphasis on China and India.

When Hokusai produced the images, Japan was still under sakoku, a policy of national isolation that began in the 1630s and lasted until 1853.

“Hokusai clearly intended to create a book that basically enabled travels of the mind at a time when people in Japan could not travel abroad,” Frank Feltens, an assistant curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art, tells Atlas Obscura. “It captures his incredible powers of creativity, fusing what he saw around himself but also what he had in his own imagination.”

Feltens adds, “Especially in the early-19th century, that longing for the exotic and the unknown became incredibly pronounced in intellectual circles.”

Hokusai was an incredibly prolific artist, producing an estimated 30,000 images over his 70-year career. With the addition of these 103 drawings, the British Museum now houses a collection of more than 1,000 of his works.

As Feltens told Smithsonian magazine’s Roger Catlin last year, Hokusai was most prolific in the last decade of his life. In the artist’s own words, it was only at age 73 that he finally “understood the structure of animals, birds, insects and fishes, and the life of grasses and plants.”

Hokusai died in 1849 at age 90—a “Biblical age at a time when the life expectancy was much lower,” according to Feltens.

“These works are a major new re-discovery, expanding considerably our knowledge of the artist’s activities at a key period in his life and work,” says Tim Clark, an honorary research fellow at the British Museum, in the statement. “All 103 pieces are treated with the customary fantasy, invention and brush skill found in Hokusai’s late works and it is wonderful that they can finally be enjoyed by the many lovers of his art worldwide.”

The acquisition comes amid growing conversations about Western museums’ ownership of other cultures’ artworks, especially collections that were acquired through colonialism. Fordham University art historian Asato Ikeda tells Atlas Obscura that the global circulation of Japanese artworks is complex because the country exported artwork as a way to gain soft power around the world.

“There has been a heated debate among specialists of Japanese art history in the past few days—about where [the collection] has been in the past 70 years and where it should belong now,” Ikeda explains. “I don’t see this as an issue about Hokusai’s drawings per se. This is a conversation fundamentally about the role of museums, the histories of which have been Western-centric and colonialist. … I still think it’s important that we have become so sensitive with the way in which museums are acquiring objects.”

Per the Art Newspaper, curators hope to use the rediscovered illustrations to draw connections with similar sketches at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. Eventually, the British Museum plans on exhibiting the works in a free display.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/84/3a/843a1df6-9a7d-4234-b6dd-b98aef71045c/073.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3b/d0/3bd00dcc-9b09-4131-a5f9-ce191cab3cb5/010.jpg)