This Initiative Is Loaning Artwork Back to the Communities They’re Most Associated With

Britain’s National Portrait Gallery’s ‘Coming Home’ initiative will loan portraits to the towns and cities most closely associated with their subjects

“It’s coming home!” You may have heard football fans (or soccer fans, as they’re known stateside) in the United Kingdom chanting the refrain throughout the 2018 FIFA World Cup.

The phrase dates back to the 1996 pop single “Three Lions,” a lyric which Jamie Grierson explains for the Guardian was intended to reference England’s hosting of its first major football tournament in three decades, but now serves as shorthand for England’s dream of winning the World Cup and its hopes of bringing the trophy back to the “disputed spiritual home of football.”

The Brits didn’t bring home the cup this year (their dreams were dashed by Croatia’s 2-1 victory during the semi-finals), but a new initiative launched by London’s National Portrait Gallery (NPG) is giving new life to the refrain of “it’s coming home”—although in this case, “it” refers to 50 portraits from the gallery’s collection, and “home” refers to the towns and cities most closely associated with their subjects. The project, fittingly entitled “Coming Home,” may not have quite the same ring as “football’s coming home,” but it promises to be spectacular all the same.

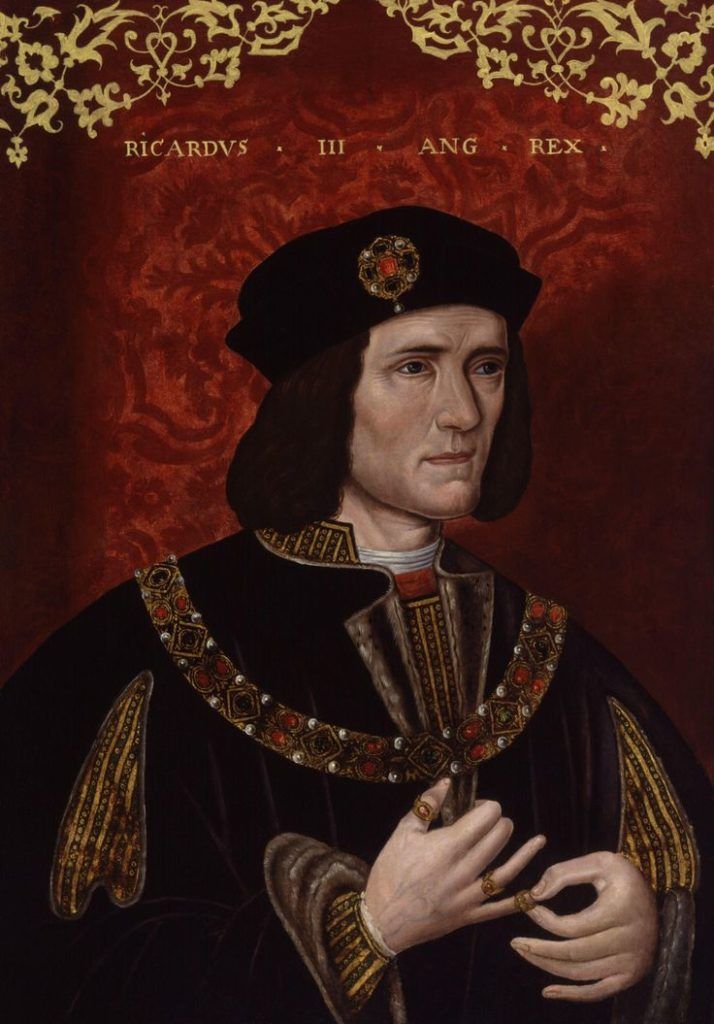

Earlier this week, the NPG announced that “Coming Home” will launch in 2019 with the first six of 50 eventual loans. The chosen works feature a mixture of traditional painted portraits—including one of Richard III, the 15th-century Plantagenet king who inspired a Shakespeare play and is rumored to have ordered the murder of his nephews, the "Princes in the Tower"—and contemporary offerings, as represented by a 2002 “Death Mask” by the Young British Artists movement’s Tracey Emin and a 2012 Kate Peters photograph of heptathlon champion Jessica Ennis-Hill.

NPG director Nicholas Cullinan tells the Guardian’s Mark Brown that the project is “unique, inclusive and ambitious. We hope that sending portraits ‘home’ in this way will foster a sense of pride and create a personal connection for local communities to a bigger national history.”

Richard III’s portrait, which was painted by an unknown artist sometime during the late 16th century, is headed to the New Walk Museum and Art Gallery in Leicester, the city where the deposed king’s remains were discovered in 2012. The oil painting depicts Richard, eyebrows creased in thought, dressed in regal finery and fiddling with a ring on the pinky finger of his right hand. According to the NPG, the portrait has alternatively been interpreted as “evidence of his cruel nature and by others as evidence of his humanity.”

Emin’s death mask stands at the opposite end of the artistic spectrum. Cast in bronze, the mask cements the artist’s image in time, hinting at the intimately autobiographical nature of her work and simultaneously upending the male-dominated tradition of leaving behind a death mask. As curator Rab MacGibbon told Brown of the Guardian in April 2017, Emin’s mask “blurs the distinctions between life and death, art and identity.”

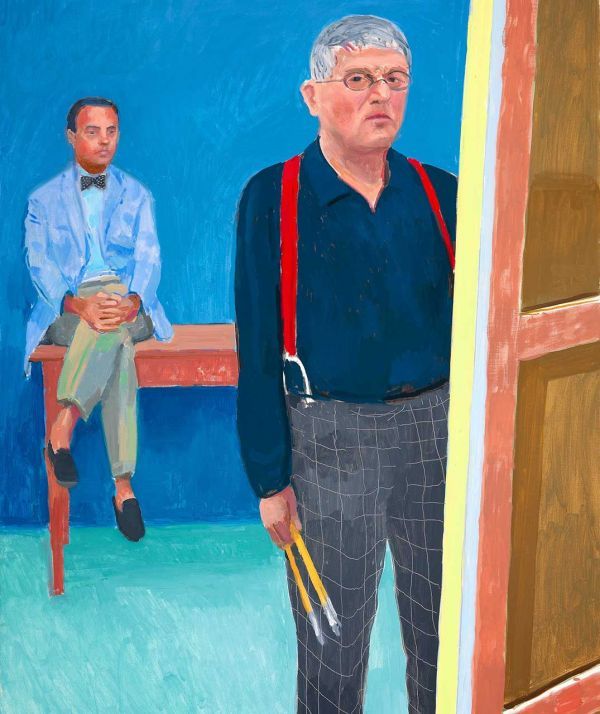

Four of the six “Coming Home” works are destined for their sitters’ hometowns: The Emin and Ennis-Hill portraits will travel to Margate, Kent, and Sheffield, respectively, while a 2005 self-portrait by pop artist David Hockney is set for display at Cartwright Hall Art Gallery in Bradford. The fourth, an unfinished portrait of abolitionist William Wilberforce, will go to Hull’s Ferens Art Gallery.

Wilberforce’s portrait, painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence in 1828, was one of the first works acquired by the NPG. Despite its unfinished state, the painting was lauded as a masterful representation of the statesman’s “intellectual power and winning sweetness.”

The last of the six portraits, Emma Wesley’s 2006 acrylic painting of soldier Johnson Gideon Beharry, will be displayed at the PWRR & Queen’s Museum in Dover. Beharry, who was awarded the Victoria Cross—the country’s highest military decoration for valor—in 2005, appears in full military dress. He meets the viewer’s gaze head-on, the faintest trace of a smile linger on his face.

With just six of the 50 anticipated loans determined, the NPG says it will continue to work with museums, galleries and other venues to identify additional portraits to be sent back to the places their subjects are most associated with.

“Every corner of the UK has well-known faces who have played a significant role in our nation’s history,” newly appointed UK culture secretary Jeremy Wright said in a statement. “I am delighted that 50 of these famous figures will be returning home so that current generations can be inspired by their stories.'"

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)