Remains of Enslaved People Found at Site of 18th-Century Caribbean Plantation

Archaeologists conducting excavations on the Dutch island of Sint Eustatius have discovered 48 skeletons to date

:focal(726x754:727x755)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9e/19/9e19d2ef-4e9f-47f3-933f-2b08640e35ba/archaeologists.jpeg)

By some estimates, European merchants transported more than four million enslaved Africans to the Caribbean islands between the 16th and 19th centuries. Because of the brutal nature of the transatlantic slave trade, most information about these individuals comes from the official records of their enslavers—an oft-biased record that favors the perspective of the colonizer. Historical sources that reflect the lived experiences of enslaved people from their own point of view are few and far between.

A newly discovered 18th-century burial ground is poised to provide crucial insights into the daily lives of individuals enslaved on Sint Eustatius, a Dutch-controlled island in the Caribbean. Experts tell the Associated Press (AP) that the site could yield information about these people’s beliefs, diets, customs, cherished belongings and more.

Per a local government statement, archaeologists are excavating the site ahead of planned expansion of a nearby airport. Fourteen scholars, including researchers from Yale University and Dutch institutions, traveled to the island for the dig, which began on April 21 and is scheduled to continue through the end of June.

Based on a 1781 map of the island, archaeologists believe they are currently excavating the remains of the former Golden Rock Plantation’s slave quarters. To date, the team has uncovered 48 skeletons at the gravesite. Most are male, but several belong to women or infants.

The researchers expect to locate more remains as work continues.

“We knew the potential for archaeological discoveries in this area was high, but this cemetery exceeds all expectations,” Alexandre Hinton, director of the St. Eustatius Center for Archaeological Research (SECAR), which is conducting the dig, tells the AP.

As Dutch broadcaster NOS reports, Hinton predicts that the burial ground may turn out to be as big as one discovered at Newton Plantation in Barbados. During the 1970s, researchers excavated the remains of 104 enslaved people interred at Newton between roughly 1660 and 1820.

In addition to the 48 skeletons, archaeologists at Golden Rock have discovered intact tobacco pipes, beads, and a 1737 coin depicting George II of England. The rusted currency was found resting on a coffin lid, per the AP.

“Initial analysis indicates that these are people of African descent,” Hinton tells the AP. “To date, we have found two individuals with dental modification that is a West African custom. Typically, plantation owners did not allow enslaved persons to do this. These individuals are thus most likely first-generation enslaved people who were shipped to [Sint] Eustatius.”

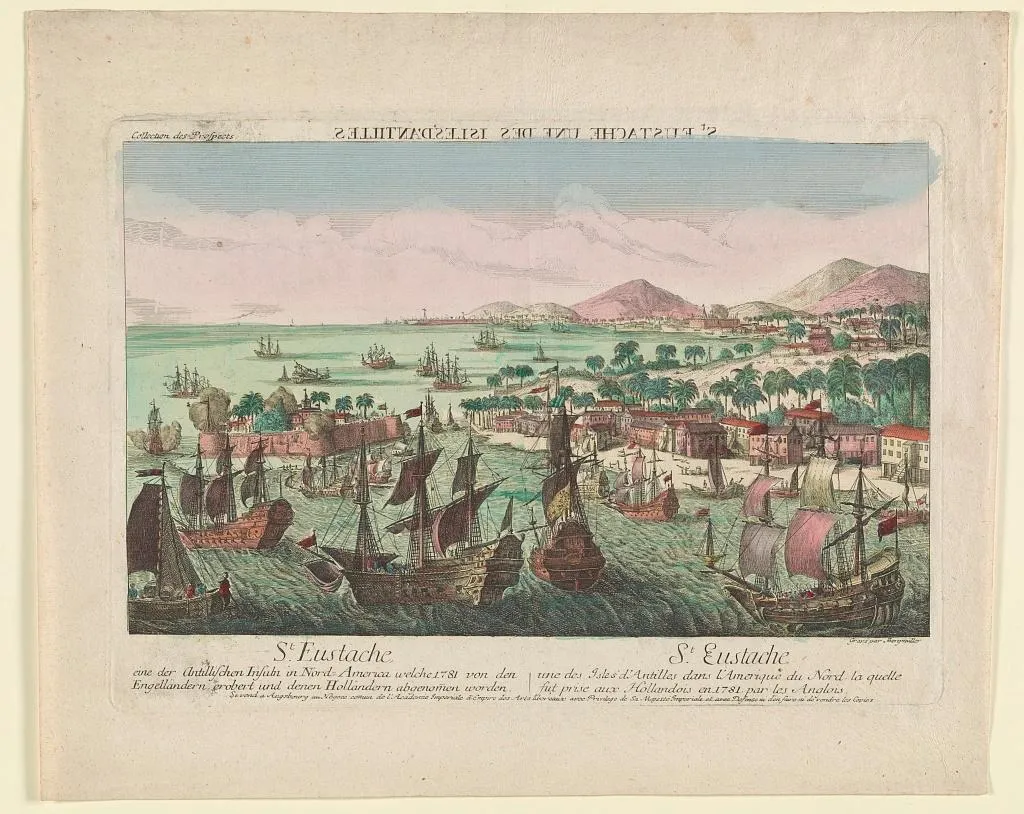

European forces first colonized Sint Eustatius in 1625, with the Dutch government gaining control of the land in 1632. In the subsequent centuries, notes Encyclopedia Britannica, the 6- by 3-mile plot of land became a focal point of the transatlantic slave trade, undergoing alternating periods of British, French and Dutch colonization.

According to a 2014 SECAR report, 840 enslaved Africans lived on Sint Eustatius in 1665. By the early 1790s, nearly 5,000 of the island’s 8,000 residents were enslaved people who lived and worked on sugar cane, cotton, tobacco, coffee and indigo plantations. Thousands more were bought and sold at Fort Amsterdam, a port at the north end of Oranje Bay.

As SECAR notes in a May 4 Facebook post, the dig site is split into two sections, with the 18th-century graveyard on one side and a much older Indigenous settlement on the other. On the second side of the site, archaeologists have uncovered artifacts created by the Arawak people, who lived on the island prior to European colonization; finds range from fragments of ancient cookware to an eighth- to tenth-century A.D. conch shell ax.

Those interested in learning more about Dutch involvement in the slave trade can explore the Rijksmuseum’s new online exhibition, “Slavery.” The show tells the stories of ten individuals, including those who suffered enslavement and those who profited from it.

Included in the exhibition are blue glass beads used as currency by individuals enslaved on Sint Eustatius during the 18th and 19th centuries. Per the exhibition, local legend holds that people cast these beads into the ocean in celebration when the Netherlands formally abolished slavery in 1863. The small beads continue to wash up on the island’s shores to this day.

Editor's Note, June 7, 2021: This article previously stated that the research team included members from Yale University and Norwegian institutions. In fact, the team consisted of scholars from Yale and Dutch institutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)